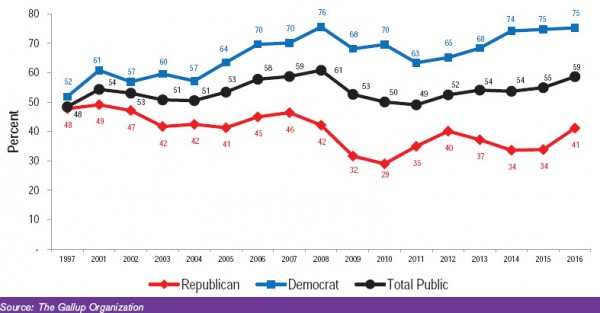

Ten years ago, Penny Edgell, Joseph Gerteis, and Doug Hartmann published a paper with a surprising finding: atheists were the most disliked minority group in the United States. More Americans said atheists didn’t share their vision of Americans society—and more said they wouldn’t like their child marrying one—than Muslims, gays and lesbians, African Americans, and a host of other groups. Today, however, more Americans have no religious affiliation, and many non-religious groups picked up on this finding as a reason to improve their public image. So, have things gotten better for atheists? The authors recently published the findings from a ten-year follow up to answer these questions, and found that not much has changed.

Despite an increased awareness of atheists and other non-religious people over the last decade, Americans still distance themselves from the non-religious. A new finding from the 2014 data is that Muslims are now statistically tied with atheists for the most disliked group in the United States. This time around, the authors asked some additional questions to get at why so many people dislike atheists. They asked if respondents think atheists are immoral, criminal, or elitist, and whether or not the increase in non-religious people is a good or bad thing. They found that one of the strongest predictors of disliking atheists is assuming that they are immoral. People are less likely to think atheists are criminals and those who think they are elitist actually see it as a good thing. However, 40% of Americans also say that the increase of people with “no religion” is a bad thing.

These findings highlight the ways that many people in the United States still use religion as a sign of morality, of who is a good citizen, a good neighbor, and a good American. And the fact that Muslims are just as disliked as atheists shows that it is not only the non-religious that get cast as different and bad. Religion can be a basis for both inclusion and exclusion, and the authors conclude that it is important to continue interrogating when and why it excludes.