Research shows that both race and class can influence health, physical activity, and exercise, yet little is known about how multiple identities intersect to influence fitness habits. If middle-class adults are more likely to exercise than low-income adults, then why are middle-class blacks less physically active than middle-class whites?

To examine how race, class, and gender all intersect to shape physical activity, Rashawn Ray designed “The Barriers and Incentives to Physical Activity Survey,” which asked 482 respondents questions about their physical activity habits as well as about how they perceived the racial composition of their neighborhood. The study only included black men, black women, white men, and white women, oversampled for black men and women, and used demographic factors like occupation, education level, and income to identify middle-class respondents.

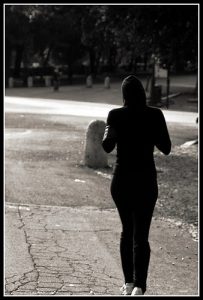

Ray found that the perceived blackness of a neighborhood had a remarkable influence on who participates in physical activity. Most notably, he found that “black men’s level of physical activity significantly decreases in neighborhoods perceived to be predominantly white whereas black women’s physical activity significantly decreases in neighborhoods perceived to be predominantly black and urban.” Unsurprisingly, white women and white men are more likely to be physically active when living in neighborhoods that are predominantly white.

Ray draws from intersectionality and feminist literature to make sense of the findings. Women’s concerns about safety and street harassment, Ray suggests, may influence black women’s reduced activity in neighborhoods perceived of as less safe, which are typically urban and predominantly black. Safer, more affluent neighborhoods are also more likely to have resources like childcare and women’s-only fitness spaces that could increase the likelihood of physical activity. On the other hand, black men experience frequent criminalization and may avoid physical activity in predominantly white neighborhoods where they are perceived as threatening. They may opt to exercise in predominantly black neighborhoods, even though these neighborhoods were identified as having fewer resources than white neighborhoods.

These findings highlight the complex relationship people have with their bodies, their activities, and their communities. It also suggests that for many black men and women, the risks associated with physical activity may outweigh the benefits of exercise.