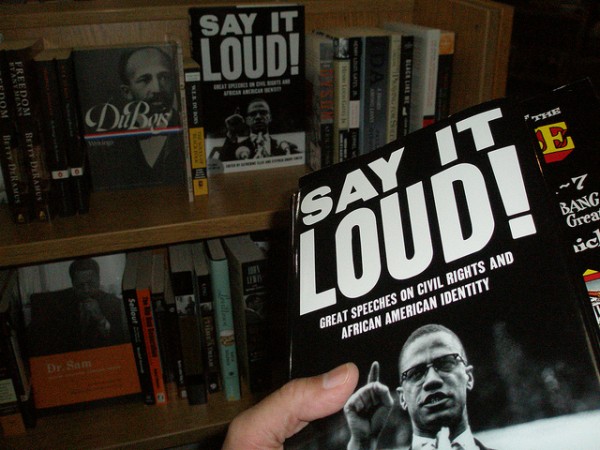

Social scientists debate the extent to which education and cognitive ability influence individual prejudices against blacks and support for policies that seek to lessen racial inequality. On one hand, higher education levels (cognitive abilities) may lead the embrace of ideologies of racial equality and tolerance. On the other hand, support for racial equality in principle is not the same as support for specific policies seeking to reduce racial inequalities. That difference could indicate that white people with higher cognitive abilities are not necessarily less racist—perhaps they are more able to express their beliefs without appearing overtly racist.

Sociologist Geoffrey T. Wodtke set out to investigate. In a new paper, Wodtke examines the responses of over 44,000 whites in various cohorts from 1972 to 2010 using data from the General Social Survey. Unlike prior studies, he reports participants’ verbal abilities (one aspect of cognitive ability) through the Gallup-Thorndike Verbal Intelligence Test on racial attitudes including anti-black prejudice, integration, discrimination, and policies aimed at racial equality. Wodtke also tests whether the period of people’s political socialization—before the civil rights movement or after—impacts the extent to which respondents’ verbal ability influences their prejudices for or against blacks and racial equity policies.

Wodtke’s findings demonstrate that whites with higher verbal abilities are less likely to support anti-black prejudice and racial segregation, and they are more aware of the discrimination that blacks face. At the same time, they are not more likely—in some cases, they are even less likely than others—to favor specific policies seeking to reduce racial inequality, such as the busing programs of the 1970s, financial aid for minority schools, and government assistance programs. Additionally, the apparently liberalizing effects of education do not appear across generations. Wodtke finds that whites’ verbal abilities have a much smaller impact on racial attitudes among those generations socialized prior to the civil rights movement, and even among post-civil rights, high verbal aptitude whites, attitudes on racial inequality in principle for have not translated into more support for policies supporting racial equality. Rhetorical abilities aside, attitudes mean little without action.