Since 9/11, Arab Americans have experienced various forms of harassment and repression in the U.S., including deportations, FBI questioning, citizen surveillance, and harassment as well as insults, threats, and physical attacks we might now categorize as hate crimes. Sociologists Wayne Santoro and Marian Azab are interested in how these experiences impact Arab Americans’ political activism, with a particular focus on protests.

Using Michigan as their case study, Santoro and Azab focus on two main questions. First, to what extent are documented levels of repression associated with increases in public demonstrations and meetings between Detroit-area Arab Americans and authorities about ethnic-based grievances? And second, which Arab Americans are more likely to be involved in activism and civic engagement?

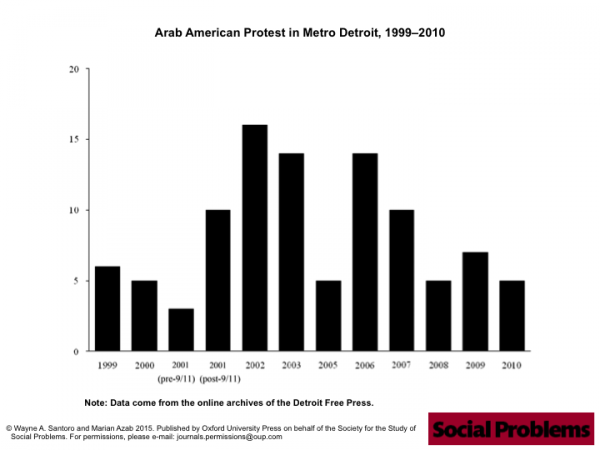

To answer the first, Santoro and Azab examined archives of the Detroit Free Press from 1999-2010. They found a clear temporal relationship between increases in repressive treatment against Arab Americans and patterns of protest and organizing in the community. Such activism peaked in the year after 9/11, with a general increase in protest in the following years.

If the fact that protests peaked post-9/11 within the Arab-American community is unsurprising, the second question—who participated in these protests—provides new information. To examine the effects of repression on an individual level, Santoro and Azab used the Detroit Arab American Study (DAAS) to look at a sample of 1,016 people of Arab or Chaldean descent living in the Detroit area in 2003. They examined the impact of experiencing repression due to race, ethnicity, or religion on the respondent’s participation in a protest, march, or demonstration about any social or political issue within the last twelve months. The results indicated that individuals who identify weakly with their Arab identity are more likely to protest after experiencing repression.

The results indicate that repression does not just mobilize those who are already activists. Rather, repression mobilizes individuals with low levels of identity who are especially shocked by their experiences with oppression.