Visit msnbc.com for breaking news, world news, and news about the economy

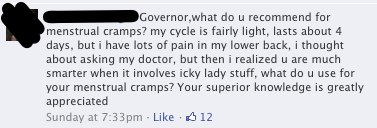

Last Friday, Rachel Maddow reported (video clip above, full transcript here) that hundreds of citizens had suddenly started posting questions on the Facebook pages of Virginia Governor Ryan McDougle and Kansas Governor Sam Brownback. Their pages were full of questions on women’s health issues and usually included some kind of statement about why they were going to the Facebook page for this information. Here’s an example from Brownback’s page:

The seemingly-coordinated effort draws attention to the recent flurry of forced ultrasound bills that are being passed in state legislatures. Media outlets have started calling it “sarcasm bombing” although the source of that term is difficult to find. ABC News simply says: “One website labelled the messages ‘Sarcasm Bombing’ for the tounge-in-cheek [sic] way the users ask the politicians for help.” A few hours of intensive googling only brings up more headlines parroting the words “sarcasm bomb” but no actual origin story. These events (which have now spread to Governor Rick Perry of Texas as well) raise several important questions but I am only going to focus on one: Can we call Facebook a “Feminist Technology”? more...