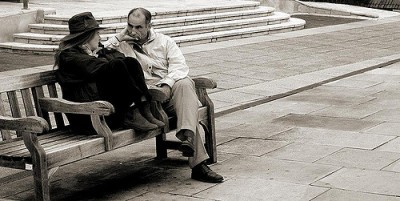

Sherry Turkle has been very successful lately. She is still touring the country giving high-profile talks and her best-selling books are assigned in college classrooms all across the country. The quotes on her books’ dustjackets are from respected authors and thinkers. She is a senior faculty member at an elite east coast university. She is by all accounts someone with an ostensibly left-of-center perspective that is popular while still pushing audiences to consider the ramifications of their actions. Turkle, through her critical analysis of social media and portable digital devices, wants people to think twice about the unintended consequences of their actions; how individual choices often aggregate into undesirable interpersonal dynamics. This is important work worthy of public debate but, precisely because it is so important, it is worth asking who benefits from Turkle’s particular brand of mindfulness.

Critiques of Turkle are too few, but the ones that exist are spot on. Focusing on individuals’ technology use, according to Nathan Jurgenson, not only turns the subjects of Turkle’s analysis into broken subhumans, it also gives the reader the opportunity to feel superior simply by fretting over when and how a device comes out of their pocket. Her work also misses, according to Zeynep Tufeci and Alexandra Samuel all the ways social media is a way of reclaiming some form of sociality in a world dominated by televisions, the suburbs, long work hours, and life circumstances that geographically separate us. Taken together we might understand the shortcomings of Turkle’s work as primarily one of digital dualism, i.e. that she considers non-mediated, in-person interaction as inherently more real or authentic compared to anything done through digital networks. What has been left unsaid, and what I want to focus on here, is how Turkle contradicts herself and, in so doing, reveals a bias toward authority and socially conservative political institutions. Turkle selectively deploys her analysis in such a way that traditional sources of authority are left unchallenged. more...