commentary

As I walk in, I glance at the sign that says “Local 1964 AFL-CIO” and smile at the greeter who stands by the front door. Walking down the aisle I peruse the household cleaners. All natural, $4; organic, $9; wood-safe, $3.Taken slightly aback by the cost, I pull out my phone and bring up the same products in the Amazon app: $1.50 difference. I pause to think about that $1.50 and spiral into an internal dialogue about capitalism and my place within it. Not only do these chemicals eventually go down my drain back into a water source that I share with my neighbors, but the money I spent represents my values. $1.50 is less than the price of a small ice cream, and also, apparently, the margin necessary to pay the local grocery workers a living wage. I pick up the product off the shelf— the $4 natural multi-surface cleaner—and continue down my list.

The presence and use of Amazon’s apps on my phone are part of a larger socioeconomic process. As gentrification runs rampant in my small city, the local use of Amazon and other delivery apps increases and local union grocery stores have closed one after another, resulting in many unemployed people. One of the many insidious aspects of late capitalism is its ability to force a competition between time-saving and wage-saving. The convenience of technology necessitates further trust in and reliance on the rest of society. Or, as PJ Rey puts it: “There is no such thing as a lone cyborg.” What we often ignore, however, is how our choice of convenience simultaneously necessitates that our local community also become more reliant on large infrastructures and less self-sustaining. As Christian Fuchs explains in Labor in Informational Capitalism and on the Internet, the unemployed class is an inevitable byproduct of technological progress in a capitalist society that must be continuously deprived of wage labor and capital. more...

“The founding practice of conspiratorial thinking” writes Kathleen Stewart, “is the search for the missing plot.” When some piece of information is missing in our lives, whether it is the conversion ratio of cups to ounces or who shot JFK, there’s a good chance we’ll open up a browser window. And while most of us agree that there are eight ounces to every cup, far fewer (like, only 39 percent) think Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone. Many who study the subject point to the mediation of the killing –The Zapruder film, the televised interviews and discussions about the assassination afterward—as one of the key elements of the conspiracy theory’s success. One might conclude that mediation and documentation cannot help but provide a fertile ground for conspiracy theory building.

Stewart goes so far as to say “The internet was made for conspiracy theory: it is a conspiracy theory: one thing leads to another, always another link leading you deeper into no thing, no place…” Just like a conspiracy theory you never get to the end of the Internet. Both are constantly unfolding with new information or a new arrangement of old facts. It is no surprise then, that with the ever-increasing saturation of our lives with digital networks that we are also awash in grotesque amalgamations of half-facts about vaccines, terrorist attacks, the birth and death of presidents, and the health of the planet. And, as the recently leaked documents about Facebook’s news operations demonstrate, it takes regular intervention to keep a network focused on professional reporting. Attention and truth-seeking are two very different animals.

The Internet might be a conspiracy theory but given the kind, size, and diversity of today’s conspiracy theories it is also worth asking a follow-up question: what is the Internet a conspiracy about? Is it a theory about the sinister inclinations of a powerful cabal? Or is it a derogatory tale about a scapegoated minority? Can it be both or neither? Stewart was writing in 1999, before the web got Social so she could not have known about the way 9/11 conspiracies flourished on the web and she may not have suspected our presidential candidates would make frequent use of conspiratorial content to drum up popular support. Someone else writing in 1999 got it right though. That someone was Joe Menosky and he wrote one of the best episodes of Star Trek: Voyager. Season 6, Episode 9 titled The Voyager Conspiracy. more...

A favorite pastime of mine is listening to podcasts or stories while playing mindless mobile games. For me, it’s the perfect blend of engagement and passivity—just enough informational input to be stimulating while still being relaxing, and put-downable enough that I can pause to do other things like prepare a meal or… get back to work. The combination of aural and visual stimulus hits just the right balance. I’m always looking for other good combinations of aural and visual input for various tasks: a TV show I can watch while organizing my PDFs, the right music for reading, another for writing, and so on. Proliferation of media texts, and the increasing availability of them, has made much of my life a mixing and matching of sensory inputs. more...

Contemporary political campaigns are highly data-driven. Large datasets let campaign staffers learn about, access, and ultimately persuade potential voters through hyper-local messaging or micro-targeting. The digitization of society means that people leave traces of themselves in the course of everyday life—how they consume, who they love, when their next menstrual cycle is likely to begin and most relevant here, how they have engaged politically. These traces and advanced analysis of them, have been instrumental in political campaign strategies, guiding staffers in numbers-based decisions about how to best reach and acquire, voters. Many partially attribute Obama’s 2008 and 2012 successful Whitehouse bids to his team’s skillful use of voter data and micro-targeting, and an uproar ensued with Bernie Sanders temporarily lost access to a DNC voter database.

Contemporary political campaigns are highly data-driven. Large datasets let campaign staffers learn about, access, and ultimately persuade potential voters through hyper-local messaging or micro-targeting. The digitization of society means that people leave traces of themselves in the course of everyday life—how they consume, who they love, when their next menstrual cycle is likely to begin and most relevant here, how they have engaged politically. These traces and advanced analysis of them, have been instrumental in political campaign strategies, guiding staffers in numbers-based decisions about how to best reach and acquire, voters. Many partially attribute Obama’s 2008 and 2012 successful Whitehouse bids to his team’s skillful use of voter data and micro-targeting, and an uproar ensued with Bernie Sanders temporarily lost access to a DNC voter database.

In contemporary politics, big data is a big deal. So of course, Donald Trump is not down with big data. The Associated Press is circulating a story about the discrepancy between Trump and Clinton with regard to data usage. Clinton’s campaign has embraced voter-data as a central tool of success, while in contrast, Trump has dismissed big data as “overrated” and expressed his intention to use big data in a “limited” capacity (although in the story linked above, a Trump advisor assures that the campaign will be “state of the art,” presumably including some degree of data analytics). more...

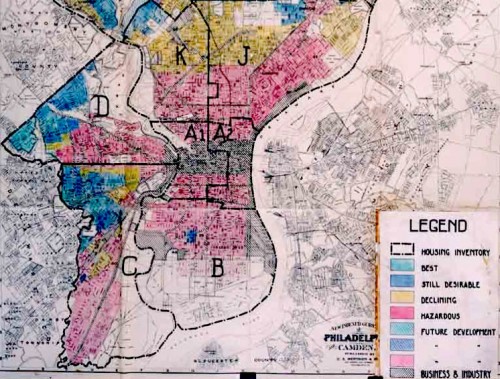

Redlining refers to the racist policy and/or practice of denying services to people of color. The term was coined in the 1960s by sociologist John McKnight and referred to literal red lines overlaid on city maps that designated “secure” versus “insecure” investment regions, distributed largely along racial faults such that banks became disproportionately unwilling to invest in minority communities. In turn, realtors showed different, more desirable properties to White clients than those they showed to clients of color, thereby reinforcing segregation and doing so in a way that perpetuated White advantage. Redlining was outlawed in the 1970s but its direct effects were intergenerational and versions of redlining continue to persist.

Versions of it like this: more...

Currently, the hashtag #WhyYouNeedTherapyInOneWord is trending on Twitter. From forums where people congregate to share strategies for combatting mental illness to essays that give a glimpse into the experience of those who have mental illness, I believe there is a strong capacity for internet communication to reduce stigma and help those in need. There is also a capacity to increase stigma, or trivialize these experiences. And sometimes a single online event can do both.

One of the most prominent theorists of the late 20th century, Michel Foucault, spent a career asking his history students to let go of the search for the beginning of an idea. “Origins” become hopelessly confused and muddled with time; they gain accretions that ultimately distort any pure search for the past on the terms of the past. Instead, his alternative was to focus on how these accretions distorted the continuity behind any idea. This method was called “genealogy,” by Nietzsche, and Foucault’s essay expanded on its use. Dawn Shepherd captured the significance of this lesson in a beautiful, single sentence: “Before we had ‘netflix and chill ;)’ we just had ‘netflix and chill.’”

One of the most prominent theorists of the late 20th century, Michel Foucault, spent a career asking his history students to let go of the search for the beginning of an idea. “Origins” become hopelessly confused and muddled with time; they gain accretions that ultimately distort any pure search for the past on the terms of the past. Instead, his alternative was to focus on how these accretions distorted the continuity behind any idea. This method was called “genealogy,” by Nietzsche, and Foucault’s essay expanded on its use. Dawn Shepherd captured the significance of this lesson in a beautiful, single sentence: “Before we had ‘netflix and chill ;)’ we just had ‘netflix and chill.’”

The temptation with something as recent as the web is to emphasize the web’s radical newness. Genealogy asks that we resist this demand and instead carefully think about the web’s continuity with structures far older than the web itself. While genealogy is not about the origins of “chill,” genealogy emphasizes the continuity of “chill.” Genealogy must build from an idea of what “chilling” entailed to say something about what “chill” means now.

Conversations about these continuities animated many of the conversations at Theorizing the Web 2016. Both the keynote panels and regular sessions asked audiences to imagine the web as part of society, rather than outside of it. In the words of its founders, the original premise of the conference was “to understand the Web as part of this one reality, rather than as a virtual addition to the natural.”

more...

Budweiser recently announced that it would rename its beer “America” for the duration of the US election season. The rebranding was described as a testament to the “shared values” of Budweiser and America, and their marketing firm Fast Co stated: “We thought nothing was more iconic than Budweiser and nothing was more iconic than America.” Who can disagree with that? No one, because it doesn’t make sense. But that’s beside the point.

Negative responses to the re-branding have generally taken two forms. First, folks on social media are gleefully pointing out that Budweiser is owned by a Belgian corporation. While there is some obvious cognitive dissonance happening when a Belgian corporation brands itself as America’s beer, they’re certainly not unique among products manufactured overseas that use American patriotism as a marketing tool. At least Bud is brewed in the US. But a second response to the announcement is the evergreen accusation that Bud both tastes like nothing and tastes like piss.

Some may label this moment a crisis of democracy, a moment in which the voice of The People lay inert; a moment in which the promise of citizen driven governance, shining so brightly in the glow of digitally connected screens, reveals itself as a farce.

Some may label this moment a crisis of democracy, a moment in which the voice of The People lay inert; a moment in which the promise of citizen driven governance, shining so brightly in the glow of digitally connected screens, reveals itself as a farce.

I am talking, of course, about Sir David Attenborough, or more to the point, I am talking about the $300 million British research vessel not called Boaty McBoatface.

The British National Environmental Research Council invited citizens to select the name for their new polar research vessel. It was an opportunity to bring science to the public and involve the public in scientific discovery. Anyone was allowed to submit a name, and everyone voted on their favorites. The name with the most votes was to moniker the craft. Radio personality James Hand proposed the name Boaty McBoatface. Hand’s suggestion was well received, and the citizenry irrefutably selected Boaty for the vessel’s name. Case closed, right? No, the vessel’s name is David… which sound nothing like Boaty and includes zero McFaces. more...

As I walk in, I glance at the sign that says “Local 1964 AFL-CIO” and smile at the greeter who stands by the front door. Walking down the aisle I peruse the household cleaners. All natural, $4; organic, $9; wood-safe, $3.Taken slightly aback by the cost, I pull out my phone and bring up the same products in the Amazon app: $1.50 difference. I pause to think about that $1.50 and spiral into an internal dialogue about capitalism and my place within it. Not only do these chemicals eventually go down my drain back into a water source that I share with my neighbors, but the money I spent represents my values. $1.50 is less than the price of a small ice cream, and also, apparently, the margin necessary to pay the local grocery workers a living wage. I pick up the product off the shelf— the $4 natural multi-surface cleaner—and continue down my list.

The presence and use of Amazon’s apps on my phone are part of a larger socioeconomic process. As gentrification runs rampant in my small city, the local use of Amazon and other delivery apps increases and local union grocery stores have closed one after another, resulting in many unemployed people. One of the many insidious aspects of late capitalism is its ability to force a competition between time-saving and wage-saving. The convenience of technology necessitates further trust in and reliance on the rest of society. Or, as PJ Rey puts it: “There is no such thing as a lone cyborg.” What we often ignore, however, is how our choice of convenience simultaneously necessitates that our local community also become more reliant on large infrastructures and less self-sustaining. As Christian Fuchs explains in Labor in Informational Capitalism and on the Internet, the unemployed class is an inevitable byproduct of technological progress in a capitalist society that must be continuously deprived of wage labor and capital. more...

“The founding practice of conspiratorial thinking” writes Kathleen Stewart, “is the search for the missing plot.” When some piece of information is missing in our lives, whether it is the conversion ratio of cups to ounces or who shot JFK, there’s a good chance we’ll open up a browser window. And while most of us agree that there are eight ounces to every cup, far fewer (like, only 39 percent) think Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone. Many who study the subject point to the mediation of the killing –The Zapruder film, the televised interviews and discussions about the assassination afterward—as one of the key elements of the conspiracy theory’s success. One might conclude that mediation and documentation cannot help but provide a fertile ground for conspiracy theory building.

Stewart goes so far as to say “The internet was made for conspiracy theory: it is a conspiracy theory: one thing leads to another, always another link leading you deeper into no thing, no place…” Just like a conspiracy theory you never get to the end of the Internet. Both are constantly unfolding with new information or a new arrangement of old facts. It is no surprise then, that with the ever-increasing saturation of our lives with digital networks that we are also awash in grotesque amalgamations of half-facts about vaccines, terrorist attacks, the birth and death of presidents, and the health of the planet. And, as the recently leaked documents about Facebook’s news operations demonstrate, it takes regular intervention to keep a network focused on professional reporting. Attention and truth-seeking are two very different animals.

The Internet might be a conspiracy theory but given the kind, size, and diversity of today’s conspiracy theories it is also worth asking a follow-up question: what is the Internet a conspiracy about? Is it a theory about the sinister inclinations of a powerful cabal? Or is it a derogatory tale about a scapegoated minority? Can it be both or neither? Stewart was writing in 1999, before the web got Social so she could not have known about the way 9/11 conspiracies flourished on the web and she may not have suspected our presidential candidates would make frequent use of conspiratorial content to drum up popular support. Someone else writing in 1999 got it right though. That someone was Joe Menosky and he wrote one of the best episodes of Star Trek: Voyager. Season 6, Episode 9 titled The Voyager Conspiracy. more...

A favorite pastime of mine is listening to podcasts or stories while playing mindless mobile games. For me, it’s the perfect blend of engagement and passivity—just enough informational input to be stimulating while still being relaxing, and put-downable enough that I can pause to do other things like prepare a meal or… get back to work. The combination of aural and visual stimulus hits just the right balance. I’m always looking for other good combinations of aural and visual input for various tasks: a TV show I can watch while organizing my PDFs, the right music for reading, another for writing, and so on. Proliferation of media texts, and the increasing availability of them, has made much of my life a mixing and matching of sensory inputs. more...

Contemporary political campaigns are highly data-driven. Large datasets let campaign staffers learn about, access, and ultimately persuade potential voters through hyper-local messaging or micro-targeting. The digitization of society means that people leave traces of themselves in the course of everyday life—how they consume, who they love, when their next menstrual cycle is likely to begin and most relevant here, how they have engaged politically. These traces and advanced analysis of them, have been instrumental in political campaign strategies, guiding staffers in numbers-based decisions about how to best reach and acquire, voters. Many partially attribute Obama’s 2008 and 2012 successful Whitehouse bids to his team’s skillful use of voter data and micro-targeting, and an uproar ensued with Bernie Sanders temporarily lost access to a DNC voter database.

Contemporary political campaigns are highly data-driven. Large datasets let campaign staffers learn about, access, and ultimately persuade potential voters through hyper-local messaging or micro-targeting. The digitization of society means that people leave traces of themselves in the course of everyday life—how they consume, who they love, when their next menstrual cycle is likely to begin and most relevant here, how they have engaged politically. These traces and advanced analysis of them, have been instrumental in political campaign strategies, guiding staffers in numbers-based decisions about how to best reach and acquire, voters. Many partially attribute Obama’s 2008 and 2012 successful Whitehouse bids to his team’s skillful use of voter data and micro-targeting, and an uproar ensued with Bernie Sanders temporarily lost access to a DNC voter database.

In contemporary politics, big data is a big deal. So of course, Donald Trump is not down with big data. The Associated Press is circulating a story about the discrepancy between Trump and Clinton with regard to data usage. Clinton’s campaign has embraced voter-data as a central tool of success, while in contrast, Trump has dismissed big data as “overrated” and expressed his intention to use big data in a “limited” capacity (although in the story linked above, a Trump advisor assures that the campaign will be “state of the art,” presumably including some degree of data analytics). more...

Redlining refers to the racist policy and/or practice of denying services to people of color. The term was coined in the 1960s by sociologist John McKnight and referred to literal red lines overlaid on city maps that designated “secure” versus “insecure” investment regions, distributed largely along racial faults such that banks became disproportionately unwilling to invest in minority communities. In turn, realtors showed different, more desirable properties to White clients than those they showed to clients of color, thereby reinforcing segregation and doing so in a way that perpetuated White advantage. Redlining was outlawed in the 1970s but its direct effects were intergenerational and versions of redlining continue to persist.

Versions of it like this: more...

Currently, the hashtag #WhyYouNeedTherapyInOneWord is trending on Twitter. From forums where people congregate to share strategies for combatting mental illness to essays that give a glimpse into the experience of those who have mental illness, I believe there is a strong capacity for internet communication to reduce stigma and help those in need. There is also a capacity to increase stigma, or trivialize these experiences. And sometimes a single online event can do both.

One of the most prominent theorists of the late 20th century, Michel Foucault, spent a career asking his history students to let go of the search for the beginning of an idea. “Origins” become hopelessly confused and muddled with time; they gain accretions that ultimately distort any pure search for the past on the terms of the past. Instead, his alternative was to focus on how these accretions distorted the continuity behind any idea. This method was called “genealogy,” by Nietzsche, and Foucault’s essay expanded on its use. Dawn Shepherd captured the significance of this lesson in a beautiful, single sentence: “Before we had ‘netflix and chill ;)’ we just had ‘netflix and chill.’”

One of the most prominent theorists of the late 20th century, Michel Foucault, spent a career asking his history students to let go of the search for the beginning of an idea. “Origins” become hopelessly confused and muddled with time; they gain accretions that ultimately distort any pure search for the past on the terms of the past. Instead, his alternative was to focus on how these accretions distorted the continuity behind any idea. This method was called “genealogy,” by Nietzsche, and Foucault’s essay expanded on its use. Dawn Shepherd captured the significance of this lesson in a beautiful, single sentence: “Before we had ‘netflix and chill ;)’ we just had ‘netflix and chill.’”

The temptation with something as recent as the web is to emphasize the web’s radical newness. Genealogy asks that we resist this demand and instead carefully think about the web’s continuity with structures far older than the web itself. While genealogy is not about the origins of “chill,” genealogy emphasizes the continuity of “chill.” Genealogy must build from an idea of what “chilling” entailed to say something about what “chill” means now.

Conversations about these continuities animated many of the conversations at Theorizing the Web 2016. Both the keynote panels and regular sessions asked audiences to imagine the web as part of society, rather than outside of it. In the words of its founders, the original premise of the conference was “to understand the Web as part of this one reality, rather than as a virtual addition to the natural.”

more...

Budweiser recently announced that it would rename its beer “America” for the duration of the US election season. The rebranding was described as a testament to the “shared values” of Budweiser and America, and their marketing firm Fast Co stated: “We thought nothing was more iconic than Budweiser and nothing was more iconic than America.” Who can disagree with that? No one, because it doesn’t make sense. But that’s beside the point.

Negative responses to the re-branding have generally taken two forms. First, folks on social media are gleefully pointing out that Budweiser is owned by a Belgian corporation. While there is some obvious cognitive dissonance happening when a Belgian corporation brands itself as America’s beer, they’re certainly not unique among products manufactured overseas that use American patriotism as a marketing tool. At least Bud is brewed in the US. But a second response to the announcement is the evergreen accusation that Bud both tastes like nothing and tastes like piss.

Some may label this moment a crisis of democracy, a moment in which the voice of The People lay inert; a moment in which the promise of citizen driven governance, shining so brightly in the glow of digitally connected screens, reveals itself as a farce.

Some may label this moment a crisis of democracy, a moment in which the voice of The People lay inert; a moment in which the promise of citizen driven governance, shining so brightly in the glow of digitally connected screens, reveals itself as a farce.

I am talking, of course, about Sir David Attenborough, or more to the point, I am talking about the $300 million British research vessel not called Boaty McBoatface.

The British National Environmental Research Council invited citizens to select the name for their new polar research vessel. It was an opportunity to bring science to the public and involve the public in scientific discovery. Anyone was allowed to submit a name, and everyone voted on their favorites. The name with the most votes was to moniker the craft. Radio personality James Hand proposed the name Boaty McBoatface. Hand’s suggestion was well received, and the citizenry irrefutably selected Boaty for the vessel’s name. Case closed, right? No, the vessel’s name is David… which sound nothing like Boaty and includes zero McFaces. more...