Science. Is. Political.

This concept will probably be easy to absorb for the regular readership at Cyborgology. It’s a topic that has been discussed here a time or two. Still, as truisms go, it is one of a very few that liberals and conservatives alike love to hate. The fantasy of apolitical science is a tempting one: an unbiased, socially distant capital-s Science that seeks nothing more than enlightenment, floating in a current events vacuum and unsullied by personal past experiences. It presupposes an objective reality, a universe of constants that can be catalogued, evaluated, and understood completely. But this view of science is a myth, one that has been thoroughly dissected in the social sciences.

As often as the myth of scientific apoliticism comes into conflict with the messy reality, it is no wonder that scientific and technical expertise is often questioned in the policymaking realm. The term “anti-science” gets thrown around a lot in the United States, especially in reference to the Trump administration and the majority-Republican Congress so eager to curry favor with him.

One organization is attempting to move the needle away from anti-science policy. Founded by a STEM professional and entrepreneur, 314 Action is a political action committee geared specifically toward getting more scientists to run for elected offices at all levels of government. The PAC takes its name from the first three digits of pi, because “[p]i is everywhere. It’s the most widely known mathematical ratio both inside and out of the scientific community. It is used in virtually everything we encounter in our daily lives.” If science can be found everywhere, the logic goes, then science definitely belongs in the halls of power and decision-making as well.

From the PAC’s website:

314 ACTION’S GOALS ARE:

Strengthen communication among the STEM community, the public and our elected officials;

Educate and advocate for and defend the integrity of science and its use;

Provide a voice for the STEM community on social issues;

Promote the responsible use of data driven fact based approaches in public policy;

Increase public engagement with the STEM Community through media.

314 Action champions electing more leaders to the U.S. Senate, House, State, Executive and Legislative offices who come from STEM backgrounds. We need new leaders who understand that climate change is real and are motivated to find a solution.

We need elected officials who understand that STEM education is the new path forward, vital for our future and will ensure that our educators have the necessary funding to teach STEM curricula and our students have the resources to learn. That is why 314 Action will advocate for a quality, adequately funded STEM education for every young person in the United States.

But this begs the question: can placing more STEM professionals in Congress save science policy, or will it only produce more lifetime politicians?

In politics, anti-science and pro-science aren’t opposites. They’re two strategies toward the same end of winning and keeping political power. The struggle between these two political stances is a constant, dynamic, situationally contingent negotiation between the social prestige of scientific evidence and the political necessity to control the vocabulary and optics surrounding a given policy topic.

Anti-science doesn’t mean that politicians don’t believe in science. It means that they have a hard time reconciling scientific findings with more pressing political concerns, like fundraising from special interest donors and mollifying their constituencies. These day-to-day political tasks require total control over a political narrative with a kind of hyperreality and spectacle that leaves little room for the slow pace and uncertainty of scientific research.

And, pro-science doesn’t necessarily mean a belief in the power of science to craft good policy. As my own research has shown, scientific debates often stand in for debates about money and legislative instrumentation, because scientific debate is easier to sound bite and quicker to digest across the voting public. I have found elsewhere that political actors, at least in the climate change political sphere, most often cite sources of expert information from other actors or organizations who a priori align with their political ideologies.

The candidates 314 PAC aims to mobilize are trained scientists and novice office-holders. They are not politicians. In fact, the point is largely to recruit people who have never held office before. There’s a certain amount of purity attached to a scientific expert who has never dabbled in politics. At the same time, someone willing to risk the credibility and safety of that purity seems, in this narrative, to be a brave and competent candidate. It’s like the Madonna-whore complex of science policy.

The 314 Action fundraising page acknowledges this to some extent: “Most of our candidates will not come from the traditional career paths of politicians, and will need different channels for funding and support. 314 PAC intends to leverage the goals and values of the greater science, technology, engineering and mathematics community to give these new recruits the resources they need to become viable, credible, Democratic candidates.”

And there’s the crucial point in all of this: the advocacy of 314 PAC is aimed at liberal scientific political engagement, not greater STEM engagement overall. While it is perfectly acceptable for a PAC to pin itself to a particular ideological position, it is dangerous to conflate an acceptance of scientific principles with a liberal political mindset.

Ben Carson is a brain surgeon, celebrated as a visionary in his field, but has demonstrated time and again his tenuous grasp on history, political science, and reality. Former US Representative Todd Aiken—he of the “if it’s a legitimate rape, the female body has ways to try to shut that whole thing down” infamy—was a leader in the Army Corps of Engineers. Rand Paul is an ophthalmologist who ran for president on a platform of small government— so small that it had little room at all for research and development. The lesson here is clear: being in the STEM fields alone does not make you pro-science, being pro-science alone doesn’t make you smart, and being smart alone will not make you an effective policymaker.

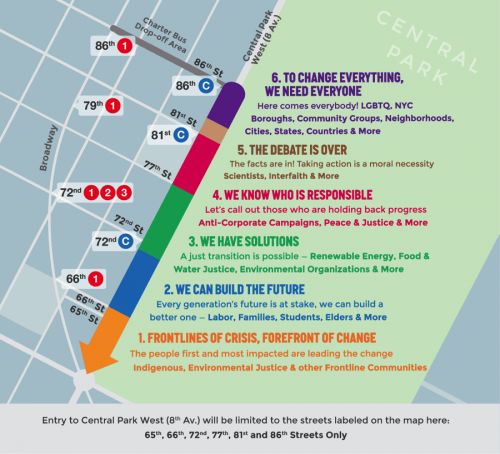

None of this is to say that scientists and engineers should stay away from politics. Far from it; democracy thrives when rooted in a diversity of perspectives and consideration of all available evidence. See the first line of this post. Exposure and intersectionality are critical foils to a democracy that has grown comfortable with status quo politics and ideological purity. And scientists are human beings, voting citizens, paying consumers. They deserve a political opinion, and indeed can’t help but have one.

Furthermore, the efforts of 314 also seem to be having the unintended consequence of inspiring more women and people of color to run for office from within the STEM fields. 314 Action’s founder, Shaughnessy Naughton, is a woman who ran for the House of Representatives in 2016 on a pro-science platform. That women and people of color are more acutely aware of the politics present in science than their white male counterparts is no surprise, but it’s good that these scientists have a path forward for translating this awareness into political change.

Most importantly, I would point out that there is value in scientists running for office, even if they don’t win. Campaign events are major sources of information for voters, and the shiny optics and well-scripted hyperreality of a scientist’s campaign could go a long way in educating a constituency about a topic of scientific importance, even if it doesn’t sway votes that way. As I’ve written elsewhere, the novelty of a pro-science platform from either party could effectively shift voter attitudes in the age of anti-scientific policymaking.

The danger here is not in scientists running for office and losing. It is in scientists running for office, winning, and being unprepared to participate in the political process because they ran on an “I’m a scientist” platform. Congress has already shown itself to not only be open to the label of anti-science, but in many cases, has actively courted it. To assume that the prescription for political change is a critical mass of scientists in elected positions is to ignore the very messy social dynamics mediating the interfaces between science and politics.

Policymaking cares little for methodology, and even less for control conditions. Neither the constitutionally inscribed forward-facing process nor the subtler backstage deal-making that go into crafting policy are interested in scientific uncertainty and its sometimes glacial pace of innovation. Scientists should absolutely run for office. They should also march in demonstrations, write letters to their representatives, and engage in democracy as every other citizen has a right to do. But they—and the organizations supporting their candidacy for office—should be prepared for the contentious and sometimes fact-free atmosphere of US government.