As the American Sociological Society Annual Meeting approaches, I want to take this opportunity to give some theoretical attention to the language of digital technologies. The following is perhaps an overly verbose way of asking what to do with heavily integrated but problematic vocabularies? The timing here is significant, as I believe the meetings next weekend will include a lot of dualist language that we, as a discipline, aren’t quite sure what to do with.

*****

Bloggers here at cyborgology ascribe to several different theoretical and methodological perspectives. However, we share two related assumptions. First, humans and technologies are—and always have been—mutually constitutive. In light of this, our second shared assumption is that it is problematic to discursively dichotomize humans and technologies. The first point refers to an augmented perspective, and the latter point refers to the digital dualism critique.

Over time, we have all written extensively in an effort to articulate, tweak, argue, and apply the augmented perspective and digital dualism critique (see links above). As many of us now look towards constructing more formal essays (i.e., peer-reviewed books/chapters/articles) from this line of theorizing, we find ourselves struggling with linguistic precision. Language is tricky, as it is always value-laden and yet masquerades as neutral, quietly coaxing speakers and writers into complacence and uncritical usage. Or put more simply, it is easy to rely upon existing words, difficult to see the problems with those words, and really difficult to come up with new words that a) avoid problems with existing words, and b) effectively communicate meaning.

In tackling this language problem with regards to new technologies, several of us got together to hash out some of the stickier points. The following discussion is born of this meeting.

*****

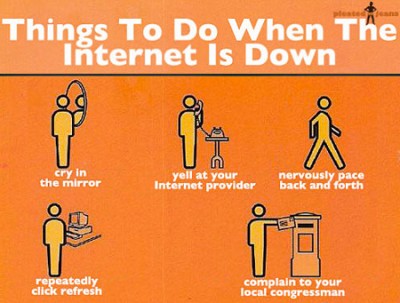

We spent the better part of the morning talking/fighting/coming up with numerous analogies about the language of “online” and “offline.” These terms are of particular importance because they are both inherently dualist—as they imply that “on” and “off” are separate and mutually exclusive states— and also very widely used in both common parlance and academic writing.

Our main question was this: How do we talk about the colloquial words online and offline, and in particular, the conditions under which actors[i] can be designated as online or offline, in a way that captures its many normative uses yet avoids problematic dualisms and definitional conflations?

In response to this question, I offer the language of “ network access.” I argue that the language of network access allows for precision while remaining comprehensible to a broad audience and maintaining dialogue with established works. I begin with a delineation of the many things that people mean when they say online and offline, and then offer network access as an alternative linguistic tool.

*****

When people say online and offline, they actually mean several different things, some of which are contradictory. We can categorize three meanings of online and offline as currently connected, potentially connected, and maintaining a presence.

1) Currently Connected: Something an actor is currently doing

An actor is online if they are interacting on the Internet, with a device connected to the Internet, right now. They are offline if they are not interacting on the Internet right now. For example, I am online right now because I am currently interacting with WordPress—an Internet connected blogging platform. When I close my computer and walk to the kitchen to get a snack, I am no longer online. While out with friends, I may spend a few moments sending a Tweet. For those moments, I am online. When I put my phone back in my pocket, I am offline.

2) Potentially Connected: Something an actor could potentially be doing

An actor is online if they can potentially interact on the Internet. For example, students in a WiFi connected university library are online in the sense that they can, at any given moment, connect to the Internet using a university ID and password. They need not actually do so in order to be online. Rather, connecting must simply be an available option. Visitors to the library without a university ID or password, however, cannot potentially connect to the Internet, and are therefore offline. Similarly, the University is online if they offer WiFi, but offline if they do not.

3) Maintaining a Presence: An actor exists on the Internet

An actor is online if they maintain any sort of online presence. That is, the actor is online if someone can find them—or their traces—in any capacity. For example, if a teenager maintains a Facebook page, a business maintains a website, or someone posts an image of a piece of architecture to Instagram, these actors are all online. Without the Facecbook page, website, and Instagram image, these actors would be offline.

*****

Clearly, online and offline are over-coded terms. A more precise way to talk about the multiple meanings of online and offline, I argue, is with the language of network access:

When an actor is currently interacting with a device that is connected to the Internet, we can say that the actor is accessing the network and/or accessed by the network. This maintains a sense of active doing, but also recognizes the precarious role of intentionality. An actor need not decide to access the network to be on the network. For example, I am accessing the network through WordPress (active doing) but as I work on this post in the airport terminal, some other actor may also put me in the network through, for example, taking and sharing an image of me with their phone, or recording me with Google Glass—with or without my knowledge and/or consent. That is, I am both accessing the network, and potentially accessed by the network.

When an actor could potentially interact with a device that is connected to the Internet, we can say that the actor has access to the  network. Here, we can talk about issues of digital divide, discerning who has access, when, and to what extent. For example, I may not have access to the network while riding on the metro, entering a particular building, or hiking through the woods, but do have an active network connection in my home, on my phone, in a coffee shop, etc. In those moments in which I cannot access the Internet, such as when I go through tunnels on my metro ride, I am not online. In the moments in which I do have access to the network, such as at home, at my university, in the airport terminal etc., I am online. Because my access to the network is relatively robust, being offline, in the sense of having access, is always a temporary state. Similarly, when a conference offers participants access to the network, the conference is online, but when the network falters due to overload we can say that the building and conference are offline. We can compare this to situations in which lack of access is more persistent, such as cities without digital infrastructures, or people who may only have access in public places, and/or have no access due to lack of infrastructure, lack of technical knowledge/skills, lack of connection-capable devices, etc.

network. Here, we can talk about issues of digital divide, discerning who has access, when, and to what extent. For example, I may not have access to the network while riding on the metro, entering a particular building, or hiking through the woods, but do have an active network connection in my home, on my phone, in a coffee shop, etc. In those moments in which I cannot access the Internet, such as when I go through tunnels on my metro ride, I am not online. In the moments in which I do have access to the network, such as at home, at my university, in the airport terminal etc., I am online. Because my access to the network is relatively robust, being offline, in the sense of having access, is always a temporary state. Similarly, when a conference offers participants access to the network, the conference is online, but when the network falters due to overload we can say that the building and conference are offline. We can compare this to situations in which lack of access is more persistent, such as cities without digital infrastructures, or people who may only have access in public places, and/or have no access due to lack of infrastructure, lack of technical knowledge/skills, lack of connection-capable devices, etc.

Finally, when an actor maintains a presence on the Internet, we can say that the actor is accessible via the network. For instance, one can input a Google search for Theorizing the Web (TtW) and access its many artifacts. In this sense, TtW is online. However, these artifacts are limited to past and near-future Theorizing the Web conferences. Temporally distant TtW conferences do not yet have an online presence, and are therefore not accessible via the network. As such, TtW 2013 is online, but TtW 2015 is (for now) not.

*****

The metaphor of “on” and “off” implies a dualism that the augmented perspective works to avoid. As such, the more precise language of network access understands the conditions of connectivity to be always variable, often intersecting, never mutually exclusive, and never conflated.

Importantly, variations in type and degree of access are rooted in an assumption of inevitable connectivity. This assumption is one that we here at Cyborgology believe to be central. It is impossible for any actor to be unaffected by the Internet. Once the Internet (or any technology for that matter) exists, actors always live in relation to it in some way. That is, when asked: is an actor affecting and affected by, the Internet? The answer is unalterably, at this point, “Yes.”

As PJ Rey points out, one can log off, but can never disconnect. Those who refuse to access the network, and those electing not to maintain a presence online, do so in defiance of—but very much in relation to— digital connectivity. Moreover, refusing to access or present on the network does not preclude the network from accessing the actor, as engaging in a connected world with connected others inevitably leaves digital traces of the refusing actor(s) sprinkled throughout the web. Further Those involuntarily excluded from network access suffer consequences of that exclusion vis-a-vis those who do have and use their access.

I close now not with a prescription, but with a big question. What do we do with the terms online and offline? They are widely used, widely recognized, and convey meaning in important ways. And yet, we have just spent a good deal of work (me writing, you reading) discussing the problems with their usage. What happens if we throw them out? What does it mean if we do not? If these terms hold dualist connotations, do we perpetuate dualisms through continued implementation? On the other hand, do we break off dialogue (and if so, with whom) by excluding the terms from our intellectual repertoire? This is an important question for the terms at hand, but also more generally. Online and offline only scratch the surface of dualist language. If the goal is theoretical progression while maintaining broad communication, we must tread carefully in our treatment of established linguistic tools.

[i] “Actor” does not necessarily mean “person.” Rather, and actor can be a person, institution, company, collective, or object.

Jenny Davis is a regular contributor to Cyborgology. Follow Jenny on Twitter @Jenny_L_Davis

Pic Creds:

What to do: http://media.techeblog.com/images/internet_down.jpg

Comments 9

@adpaskhughes — August 2, 2013

These seem to me to be similar arguments to Don Slater's (2002) chapter on "social relationships and identity on-line and off-line" and much of Nancy Baym's work, although I'm not sure what their 'solutions' would be.

The question of breaking off dialogue is interesting, given that Slater seems to suggest that people don't really talk with this distinction in mind (the ideas are outdated, in other words - nobody thinks in terms of "online" and "offline", or of "cyberspace", etc.).

I'm not convinced that digital dualism is anything other than a fallacy arising from early internet research that only continues to be perpetuated in mainstream media opinion pieces.

My assumption is essentially that people's "lay" or "vernacular" understandings of "online" and "offline" are likely to be very nuanced and - because of this - that people will have already have found a way around these linguistic "traps". Perhaps these terms simply have been abandoned in day-to-day talk about the internet and connectivity? Perhaps there are already existing ways of talking about the three different meanings of 'online'? It seems to me that this necessitates more research into how people talk about and around the internet.

Atomic Geography — August 2, 2013

I guess I'm not bothered by off/on line. I see it similar to indoors/outdoors. So I could be currently indoors, potentially indoors and maintaining an indoors presence.

There are gradations of in/out doors. For instance I am writing this on a porch.

Similar moral disapproval has been placed, in some times/places, on those who send too much time in/out doors because the experience of too much in/out doorness is seen in some way to limit one's humanity.

But for the most part the terms themselves are quite functional and convey more meaning than they obscure.

In/out doors is a binary, a duality. By itself, this seems to me to be a function of the terms as language. It seems to be a problem only when one disapproves of the experience one has of in/out doorness, on/off lineness.

Some forms of Buddhism devote a great deal of attention to the experience of nonduality. While they may discuss it a great deal, nonduality itself is only known experientially, not through language. I don't think this is where you are going in your negative assessment of duality. But I am frequently unclear here what Cyborgology bloggers ARE referring to in their negative use of the word.

So my reaction to all this would be to accept on/off line as functional terms unless someone uses them in a way that involves the problem you identify by the term duality.

In Their Words » Cyborgology — August 4, 2013

[...] “Online and offline only scratch the surface of dualist language” [...]

Stéphane Vial — August 8, 2013

Thank you, Jenny, for this inspiring reflection. It is really true that there are a lot of language problems surrounding the "augmented" and "digital dualism critique" points of view. However, my personal idea on this is that "online" and "offline" are relevant words, we should keep them.

1. First, because they are talking about the objective technical reality. It is a technical fact that you can be "on the phone" or "not on the phone", "in front of the TV" or "not in front of the TV", "online" or "offline" (which means, you're right, "accessing the network" or not, but it does not matter to me if it was in the past or if it is in the present).

2. Second, because those words are not carrying a dualist vision. Remember Nathan's "Mild Augmented Reality" point of view (http://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2012/10/29/strong-and-mild-digital-dualism/), where he states : "The digital and physical are part of one reality, have different properties, and interact." I agree on that. According to this perspective, it is not a dualist vision to consider that online and offline have different properties, if you first consider that they are part of one reality. To be a dualist must not prevent us from making relevant distinctions. It is useful and relevant to make a difference between the offline and the online. To make this difference is not to be a dualist. It is just making a difference. To be a dualist would be to consider that the online and the offline are different realities. That would be a fallacy, as we all know here as "digital monists" (another language phrase that I suggested during my presentation at #Ttw13 (http://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2013/03/18/surveillance-and-digital-dualism-a-reflection-on-theorizing-the-web-ttw13/).

3. For me, language problems much more exist with words like "virtual" and "real". Those words must be given up, as they are badly dualist. Even "digital" and "physical" are not correct and still a bit too much dualist, as bits are also made of photons. But "offline" and "online" are correct words for me (see point 1 above). They are the only ones we have in order to speak about those 2 sides of life. You know, it's like the day and the night, just both side of one single fact. It is not to be a dualist to make a difference between the day and the night ;-)

Cheers from France,

Stéphane

Digital Connection, Language, And Family » Cyborgology — September 9, 2013

[...] this essay, but it feels necessary. “Online” contains several types of possible connection, as Jenny Davis and others at Cyborgology have argued. And the “being” part is what needs to be at stake: how does the way in which we exist change [...]

Sensory Co-Presence » Cyborgology — October 9, 2013

[...] vocabulary issues that currently muddle up theorizing about technology and society. In that post, I interrogated the words “online” and “offline.” This online/offline discussion took up the better part of our day. A second issue also arose, [...]