We are currently facing a cultural crisis of authenticity. Since the early 2000s, we have seen the concept “authenticity” slowly move from margins to mainstream (Reynolds, 2011), encapsulated by feverish celebrity gossip surrounding breakout stars like Lana Del Rey, personified through the rise of the urban hipster as folk devil (those self-professed taste arbiters of cool who ride “fixies” through the urban landscape, collect obscure records, and wear vintage clothes), and exemplified in Web 2.0 and the rise of social media (especially curatorial media like LastFM and more recently, Pintrest), where we are all now encouraged to share, like, and make public pronouncements of our personal tastes. In the contemporary zeitgeist, it seems that we are all “grasping for authenticity” in an attempt to make our lives seem more important, substantial, and relevant (Jurgenson, 2011).

We are currently facing a cultural crisis of authenticity. Since the early 2000s, we have seen the concept “authenticity” slowly move from margins to mainstream (Reynolds, 2011), encapsulated by feverish celebrity gossip surrounding breakout stars like Lana Del Rey, personified through the rise of the urban hipster as folk devil (those self-professed taste arbiters of cool who ride “fixies” through the urban landscape, collect obscure records, and wear vintage clothes), and exemplified in Web 2.0 and the rise of social media (especially curatorial media like LastFM and more recently, Pintrest), where we are all now encouraged to share, like, and make public pronouncements of our personal tastes. In the contemporary zeitgeist, it seems that we are all “grasping for authenticity” in an attempt to make our lives seem more important, substantial, and relevant (Jurgenson, 2011).

In this environment, identity is constructed both on and offline, but our online identities are increasingly coming to define our public identities. As such, the “online commons” (Lih, 2009) becomes an important space of identity construction and conflict.

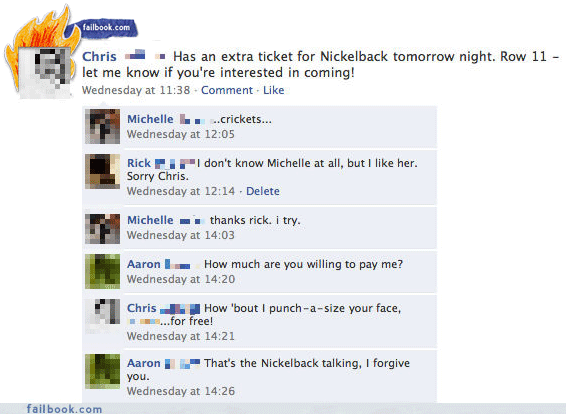

Given this crisis of authenticity, and the preponderance of social media for contemporary identity construction, it is no surprise that the digital commons, and especially various forms of social media, become spaces of conflict. On Facebook, Twitter, or Tumblr, conflicts of taste become commonplace, as one person’s proud statement becomes another’s laughing joke, fodder for ridicule and sarcasm. For example, a tweet or status professing my appreciation for the new Nickelback album [“Nickelback’s new album roolzs!”] would no doubt invite commentary like, “Nickelback is still a band?” or “Dude. You’re joking right?”.

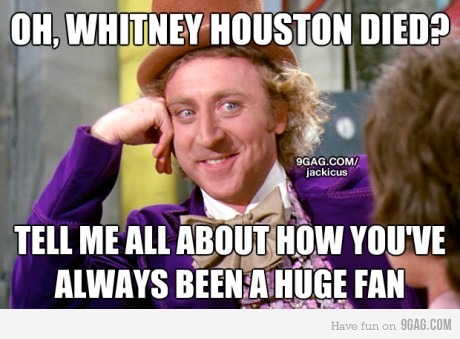

Celebrity deaths often serve as a focal point for such conflicts of taste, as individuals make identity claims by tweeting, sending a status update, or creating memorial memes to share with their digital social networks, as the most recent case of Whitney Houston illustrates. However, celebrity deaths also invite counterclaims by those who either feel their identities threatened by the publicity their once-beloved-idols receive, or who feel that such public grief is unwarranted. Most internet memes that mock such public pronouncements of grief are latent with such cynicism, seeing consumers as passive and simple-minded, naively concerned with the death of their idols while more newsworthy crises and events occur elsewhere.

Internet memes, as small, packaged signifiers pregnant with shared cultural meaning, become weapons of symbolic violence in conflicts of taste that occur in social media. By symbolic violence, I amend Pierre Bourdieu’s (1989) concept slightly, in order to account for individual actions aimed at social domination or symbolic/discursive control in the curation of taste. Bourdieu originally defined used the term to refer to the process by which dominant groups secure ideological hegemony by naturalizing their positions and getting minorities to internalize these hierarchies as legitimate, a premiere example of Bourdieu’s other concept of symbolic “world-making” (Bourdieu, 1989). In the case of conflicts of taste in the digital commons, however, symbolic violence most often takes the form of individual assaults on taste cultures, trends, and fads.

Internet memes become weapons for making identity claims online. Individuals lob them at one another through the digital commons, making claims and counterclaims of authenticity, seeking to prove “true” allegiance to an act, band, celebrity, or subculture through mockery, wit, and sarcasm.

In the digital realm, identity is partially constructed by such texts, whether in the form of a meme or more directly as a status or tweet. These public pronouncements act as expressions of taste. As we know from Bourdieu, expressions of taste are latent with underlying class tensions (Bourdieu, 1984). In the contemporary moment, such conflict is epitomized by the Occupy Wall Street protests, whose rallying cry “We are the 99%!” reflects a moment in history when struggles of agency/structure are increasingly perceived as a product of corporate malfeasance.

Susannah Young observes how the current “authenticity crisis” emerges alongside fields of cultural production like advertising and public relations. She illustrates how such logic enters our self-concepts.

Ultimately, the whole authenticity issue taps into our own social anxieties over being called out on our lack of knowledge. We live at a time when almost everyone has access to enough information and cultural trends (whether within their own social networking microcosm or on a larger plane) to make ourselves dilettantes and present ourselves as experts. Close proximity to both information and experts means we should be harder to fool – but also that we’re one withering “@you” away from being “Del Rey”’d ourselves when we do get fooled. It’s a weird, delicate situation, having to prop up our own advertisements for ourselves. Did we listen enough to “I’m Every Woman” to be justifiably, authentically sad? Does it matter?

So the crisis of authenticity becomes an integral part of the self-concept, a contemporary identity tension we must all reconcile. The deployment of internet memes, often witty but sometimes hurtful, is but one way individuals discursively construct their identities online.

Comments 7

JJ — March 23, 2012

With more pathos and less explicit analysis, I'd say that http://www.hipsterrunoff.com has investigating the intersection of authenticity, taste, and the mimetic machinery behind internet identity through the lens of contemporary indie-rock/alternative music. Here is his classic post on Animal Collective, http://www.hipsterrunoff.com/2009/01/animal-collective-band-created-byforon-internet.html

While "Carlos", the anonymous man behind the blog, indulges in continual self-deprecation and irony, I think there is something sincere going on on that blog, namely, the continual experience of being "jilted" from authenticity by some quasi-inherent "inauthenticity" native to the internet.

As ideas, bands, etc. are uploaded, we cannot but treat them as "merely" virtual, even as the digital form still contains the cultural content we value. Even if an mp3 file can be copied limitless times, it still produces feelings in the listener, until the listener becomes swept up in the "memetic logic" and begins to wonder if their feelings are not simply a copy; has the virtualization of the "lifeworld" produced a virtualization of the subject?

In the parlance of hipsterrunoff, this is compounded by the internalization of market logic. We do not merely experience culture as a raw material, we encounter it as a commodity, or as a copy of a commodity, and as a result Carlos speaks of a band/songs "relevance" or its "authenticity"(always marked by quotations) which are variables that can be used to calculate a valuation in terms of "buzz". "Buzz" is, I think, the capital of taste, it is the attempt to advertise in hopes of generating more advertising(blogs, youtubes, etc.), as financial capital is the attempt to invest money in the hopes of generating more money.

Media has certainly been divorced from an ontic originality, a fact pointed out by Walter Benjamin's 1936 essay "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction", where he worries over film's capacity for replication, as opposed to the spatial and temporal uniqueness of a painting, for instance.

In our internet age, the result seems to be not the death of value as such and the reign of depreciated copies (the foretold collapse of "professionally created" "high quality" culture due to "parasitic piracy") but the ascendancy of taste.

Perhaps then, the Citizens United vs. The Federal Election Commission court decision has expressed a truth, money IS speech, speech IS money. According to Marx exchange-value usurped use-value, resulting in capitalist markets, but is it possible that media-value is currently usurping exchange value? That something is only "worth" as much as the amount of "buzz" that it can garner?

Interesting Article on Memes and Identity, and My Response. « Kulturkritik — March 23, 2012

[...] Link, the response is on their comment board, jump over to see the words wherein I reiterate old motifs (hipsterrunoff, authenticity, capitalism) and iterate new ones (virtualization, buzz, media-capital). Was that an appropriate use of “iterate”? [...]

Anne — March 24, 2012

This was a great read, and really got me thinking about memes. I think the article of this is a little negative though. I see memes more as a "story infographic." Depending on with what meme image a meme creator backdrops text, it can lend tone and context to a reader in a split second. Explained here: http://lordofgallifrey.livejournal.com/6137.html

JJ — March 24, 2012

I can't edit the post but "has investigating" should be "investigates" and "Carlos" should be "Carles".

*facepalm*

Trevor Owens — March 29, 2012

Interesting post. In my mind this dovetails with Ftrain's argument that the essential question of the web is "why wasn't I consulted." See http://www.ftrain.com/wwic.html

He analyses some of the same types of identity performance but focuses more on the web as a medium

The Seventh Disquisition: Techotomy « Disquisition — May 1, 2012

[...] Cyborgology: The Crisis of Authenticity: Symbolic Violence, Memes, Identity [...]

this article — September 30, 2013

However, the song won't hold any negative connotations

and that's what I take from the early Delta artists that I love songs about love more than anything.