Some believe Asian-Americans face a “gentler” sort of racism than other minority groups—that they are even treated with admiration as a “model minority” group. That said, the “model minority” stereotype doesn’t have negative consequences. In an Atlantic article, sociologist Adia Harvey Wingfield discusses the multiple ways Asian identities are subject to subtle but impactful experiences in everyday life.

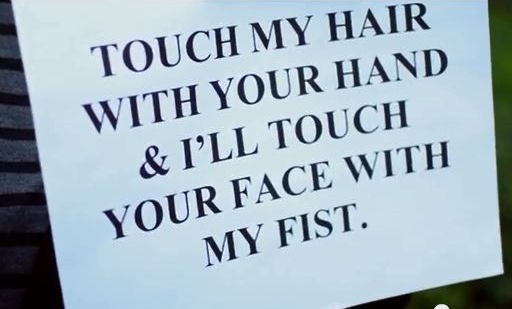

For example, consider the “model minority” stereotype, especially as it pertains to how Asians are supposed to excel at school. What this can mean, however, is that Asian-American high school students can feel deterred from seeking help when they need it, which can lead to peer isolation, among other problems, as in research by UW Madison’s Stacy Lee. Furthermore, Asian Americans are more likely to downplay racism that they face due to the implicit understanding that Asians are stereotyped in “good ways”, as descried by the Georgia State University sociologist Rosalind Chou.

That second dynamic is a part of The Racial Middle by Eileen O’Brien of Saint Leo University, a book that tackles some arguments that non-white, non-black racial identities will be subsumed into black and white, though these groups, like Latinos and Asians, are made up of sub-groups with unique histories and challenges. Consider that Asian Americans do not have a long history of organized struggle or civic action, which may reinforce the caricature of Asian groups as passive and well behaved. Collective action may raise racial consciousness in more ways than one.

To read more about Asian Americans and the Model Minority myth, see Jennifer Lee’s TSP special features “From Unassimilable to Exceptional” and “Asian American Exceptionalism and “Stereotype Promise.‘”