Election year or not, questions about voting behavior are rarely lacking among political pundits. Face it, they need stuff to talk about. Who will turn out in next year’s mid-term elections? How will the “Obama coalition” break in 2016? Social scientists are also posing questions. For example, why don’t people vote after the death of a spouse?

A study of 5.86 million Californians before and after the 2009-2010 statewide elections showed that “11 percent of people who would have voted if their spouse were alive failed to make it to the polls even a year and a half after the death.” The research found that immediately after the death of a spouse, people were less likely to vote, and while widows and widowers slowly return to the polls over time, they did not vote as often as they did before.

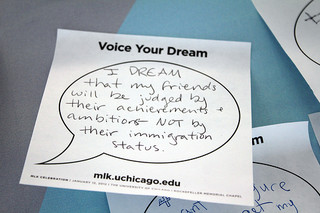

One possible explanation draws upon a central theme of sociology—the interplay of personal and public life. This study suggests that a personal tragedy leads to a withdrawal from public life. As Emma Green writes in The Atlantic, “If that’s at least somewhat true, that public life seems less important when private life collapses, then it’s also worth looking at the inverse: Do strong relationships and stable private lives make people better citizens?”

The important insights on social life that may come out of extensions of this research into wider elections, different geographic areas, socioeconomic effects, and longer-term studies, may well give the pundits and commentators something to talk about until 2016.