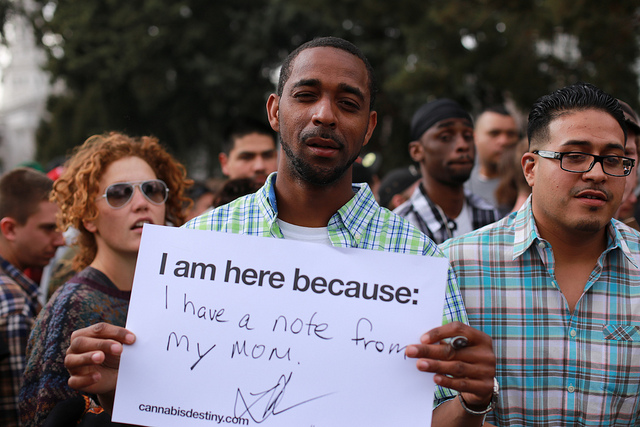

“Spark it up!” Sure, next time you’re in Colorado, you might want to stock up on Cheetos and take advantage of the state’s legalized marijuana. That is, if your skin’s the right color.

According to a new report by the Drug Policy Alliance, a pro-legalization collective, it’s already apparent that there are still racial disparities in the enforcement of the new drug laws in CO. As explained in an Associated Press article, laws that penalize carrying amounts in excess of 1oz of marijuana and the public use of the substance have disproportionately affected blacks compared to whites. Total marijuana arrests have dropped by nearly 95% since legalization, but blacks are twice as likely as whites to face sanctions under laws that criminalize illegal cultivation, public use, and excess possession. In Washington, the same phenomenon can be seen at work, the report states. In Seattle in 2014, one-third of the marijuana citations were issued to blacks, who only make up 8% of the city’s population.

According to University of Wisconsin sociologist Pamela E. Oliver, this discrepancy is indicative of African Americans’ overall treatment under the law, even after policy shifts: “Black communities, and black people in predominantly white communities, tend to be generally under higher levels of surveillance than whites and white communities… this is probably why these disparities are arising.” This discrepancy shows up in nearly all crime policing, from homicide to drug laws to robbery. In Colorado, it’s really killing the buzz.