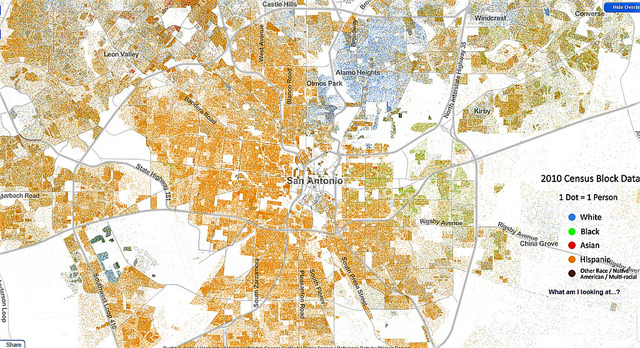

With the current presidential administration’s promises to build border walls and increase deportations, it may be surprising that Latinx immigrants report experiencing less discrimination than those born in the United States. According to a recent survey featured in NPR’s Code Switch, only 23% of Latinx immigrants report experiencing discrimination, while 44% of Latinx born in the United States report discrimination.

Sociologist Emilio Parrado told NPR that perceptions and experiences of discrimination are related to an individual’s level of participation in and adaption into United States culture. Research suggests that Latinx born in the United States may face more direct discrimination than immigrants, because they are more likely to engage in competitive workforce and social settings.

“Discrimination is a strategy of the dominant group to protect itself, to protect the benefits that they have, so discrimination is something that emerges not when people are culturally different, but that emerges when people compete.”

Parrado also argues that many immigrants come to the United States without knowing the contextual “rules” of interactions with others, which makes it harder to immediately identify instances of discrimination or racism.

“For immigrants, there is a process of learning that you are being discriminated against…Immigrants tend to think that it’s their own fault, that it’s because they don’t know the rules, or they don’t know English.”

Thus, past research may not fully capture how much discrimination is occurring simply because people may not recognize it as such. In response, some children of Latinx immigrants who were born in the United States are trying to educate their families on what discrimination looks like.