Most people think of sociology as marriage-neutral, or even anti-marriage because the institution has been linked to patriarchy, heteronormativity, domestic abuse, and a general suppression of women’s rights; however, the field has seen a shift toward a pro-marriage point of view (see, for instance, scholars like Andrew Cherlin). In the Boston Globe, Philip Cohen from University of Maryland College Park says, “Criticism of marriage as a social institution comes from the universal and basically compulsory system of marriage in the 1950s.” Since ‘50s-style marriage is no longer necessarily true, it makes sense to see an evolving scholarly outlook on the issue.

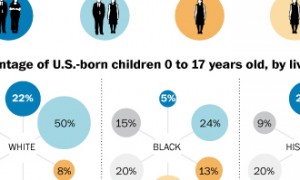

Those who say matrimony matters point to its advantages for low-income children. According to Sarah McLanahan, children with unmarried parents spend less time with their fathers and receive less financial support. Cherlin, for his part, says marriage, more so than cohabitation, contributes to family stability that leads to better child outcomes.

The evidence doesn’t necessarily mean that marriage causes the “good things” attributed to it, either. Yes, unmarried mothers tend to make less money than their married counterparts, but marriage thrives among the more educated. Those with college degrees wait longer to marry and have more resources to give their children. This means the specific people who marry make it look like married people have better outcomes, when usually they were privileged before exchanging vows. Putting a ring on it will not automatically make people healthier, wealthier, or wiser.

This disparity in findings and even recommendations about marriage points to an issue bigger than family values: “This class divide in marriage and family life is both cause and consequence of the growing inequality in American life,” said W. Bradford Wilcox, a sociologist at the University of Virginia and director of the National Marriage Project. Kristi Williams elaborates that economic circumstances can influence marriage, so trying to change marriage without fixing economic disparities is wrong-headed. Philip Cohen agrees, saying, “The idea that the culture is going downhill and we need a cultural revival happens to be very closely related to the idea that we should not address poor peoples’ problems by raising taxes and giving poor people money,” he said. “So there’s a political element” in marriage promotion efforts.