On April 21st, 2011, Harold Garfinkel, one of the important figures of the sociological canon and the man responsible for countless ‘face the wrong way in an elevator’ or ‘eat like a dog in a crowded cafateria’ introduction to sociology labs, passed away. He was 93.

The New York Times honored his passing with an account of his importance to the discipline and to broader understandings of the social world. In the article Garfinkel is attributed with the ability to draw out the complexity of even the simplest social interaction. His tendency to match the complexity of the social world with the complexity of his writing is also noted when he is characterized as:

an innovative sociologist who turned the study of common sense into a dense and arcane discipline.

Through development of the sociological approach known as ethnomethodology, Garfinkel went against the grain of the discipline by focusing on how members of society worked together to create social order rather than focusing on how the social rules determined the behaviors of individual members of society.

Mr. Garfinkel was sometimes likened to a quantum physicist because, in effect, he suggested that the fundamental building blocks of a social order were much smaller and much harder to observe than had been previously believed. Rules were not the smallest particles of social order, he found; rather, the rules themselves would be impossible without the bits of knowledge, the gestures and the methods of reasoning that allow people to communicate.

John Heritage, a professor of sociology at U.C.L.A., explains,

“His point of view wasn’t that rules aren’t important, but that how they get interpreted and applied is a matter of mutual negotiation. We have to have common resources for any form of coordinated action of human beings, and we use these common resources just to exist in a shared world. It’s a fundamental part of the human condition.”

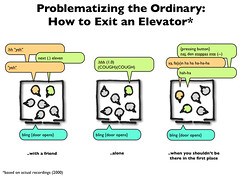

In Garfinkel’s seminal work, Studies in Ethnomethodology, published in 1967, he introduced sociologists to so-called “breaching” experiments:

in which the subjects’ expectations of social behavior were violated; for example, a subject playing tic tac toe was confronted with an opponent who made his marks on the lines dividing the spaces on the game board instead of in the spaces themselves. Their reactions — outrage, anger, puzzlement, etc. — helped demonstrate the existence of underlying presumptions that constitute social life.

As Professor Heritage explains, the book had influence beyond disciplinary walls.

“Not only did it deal with rules and language, which are fundamental elements of sociological study, but it reached across many fields: cognitive science, artificial intelligence, philosophy. You wouldn’t get any argument if you said it was among the 10 most important books in sociology in the 20th century.”

The nature and importance of Garfinkel’s academic work is best captured in the final line of The New York Times article and the first line of Heritage’s book on Garfinkel, “Notwithstanding his world renown, Harold Garfinkel is a sociologist whose work is more known about than known.” Garfinkel’s ideas are so pervasive that, within sociology, even those who have not engaged directly with his text, have had their basic assumptions shaped by his work.