With over 800 million active users, Facebook must be affecting our relationships—some even wonder if acquiring hundreds, even thousands, of online companions is helping or hindering our “real life” connections to others. It’s no surprise that new research on this topic by Cornell sociologist Matthew Brashears is making a splash in media outlets from ABC News to The Times of India and The Telegraph. Brashears work asks, even in this hyper-connected world, do we have as many close friends as we think we do?

With over 800 million active users, Facebook must be affecting our relationships—some even wonder if acquiring hundreds, even thousands, of online companions is helping or hindering our “real life” connections to others. It’s no surprise that new research on this topic by Cornell sociologist Matthew Brashears is making a splash in media outlets from ABC News to The Times of India and The Telegraph. Brashears work asks, even in this hyper-connected world, do we have as many close friends as we think we do?

In short: no. According to Brashears’ longitudinal research (which looked at over 2,000 adults from 1985 to 2010 and was published in the journal Social Networks), the average number of close friends—people with whom respondents said they’d discussed important matters with during the past six months—most of us report is two. Just 25 years ago, the average was closer to three. Brashears is quick to point out that we’re not becoming asocial. He thinks we’re getting better at being careful in selecting our confidants. Perhaps we now favor a smaller, tighter network for our true support system even while we enjoy more casual, diffuse online networks.

ABC News went a bit further to ask whether Facebook was actually to blame for this culling of comrades. The news outlet turned to a Pew Research Center report written by another sociologist, Keith Hampton of the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania. Hampton took a rosier view in a blog post on the subject:

Internet users in general, but Facebook users even more so, have more close relationships than other people. Facebook users get more overall social support, and in particular they report more emotional support and companionship than other people.

Different networks, we know, fulfill different needs. Facebook reports that its average user has 130 friends—as of this writing, there’s just no separate category for “real friends.”

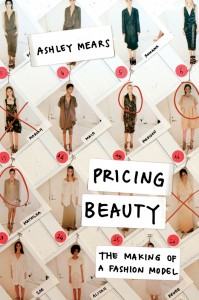

d spent some time in the New York fashion scene and looked closely among the high heels, you might have spotted one model taking scrupulous field notes as seriously as she took the runway. Ashley Mears, assistant professor of sociology at Boston University and author of the book Pricing Beauty, immersed herself into the world of modeling by actually becoming a model. A recent

d spent some time in the New York fashion scene and looked closely among the high heels, you might have spotted one model taking scrupulous field notes as seriously as she took the runway. Ashley Mears, assistant professor of sociology at Boston University and author of the book Pricing Beauty, immersed herself into the world of modeling by actually becoming a model. A recent