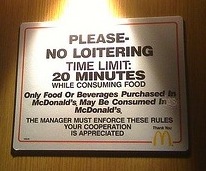

A recent incident where police officers removed elderly “loiterers” from a McDonald’s in Queens has sparked a debate over the phenomenon of spaces such as McDonald’s and Starbucks being used as impromptu senior centers. In her article for the New York Times, Stacy Torres makes excellent use of sociological ideas when defending the use of these spaces for socializing. She argues that the use of these public places as a sort of social club helps these Manhattan seniors avoid isolation and keep much needed social bonds. She turns to sociologists to explain the phenomenon:

Ray Oldenburg, a professor emeritus of sociology at the University of West Florida, calls these gathering spots “third places,” in contrast to the institutions of work and family that organize “first” and “second” places. He sees bookstores, cafes, and fast food joints as necessary yet endangered meeting points that foster community, often among diverse people. The Yale sociologist Elijah Anderson likens public settings such as Reading Terminal Market in Philadelphia to a “cosmopolitan canopy,” where people act with civility and converse with others to whom they might never otherwise speak.

Torres explains that since many of the neighborhood places such as local bakeries or cafes have disappeared, these seniors are forced to turn to institutions such as these fast food restaurants in order to provide structure and routine to their lives.

![]()