The appointments were all scheduled; the preliminary tests were done; the co-parenting agreements were signed; and the flights were booked. My wife and I were counting the days until our sperm donor, Steffan, would arrive in the U.S. to deposit his sperm. This was February 2020. Steffan was due to arrive in the U.S in April to provide his sperm donation, then several months later we planned to start our journey to grow our family in August 2020.

However, then came March 2020 and with it came COVID. Now fertility clinics were closed, international travel was limited, and our carefully thought out, well-timed plans had come to a screeching halt. Like many couples planning to conceive in 2020, the new reality drastically changed what is already a nerve-wracking endeavour.

Family building for LGTBQ folks has never been easy. For most cis/het couples who don’t face infertility issues (85-90%), the process is ideally a time for connection, romance, and the inevitable lovemaking. But for LGBTQ folks, the process is often filled with filling out legal forms, doctors’ visits, psychological tests, and major financial decisions – exacerbated by the cost of conception. Yes, technology has eased this process, given the relative accessibility of assisted reproductive technology (ART), the availability of sperm banks, and the advent of online support groups. Less and less do you hear of the queers making children in an awkward, often substance filled, turkey baster situation. However, there are still major structural barriers and a series of daunting hurdles we need to traverse.

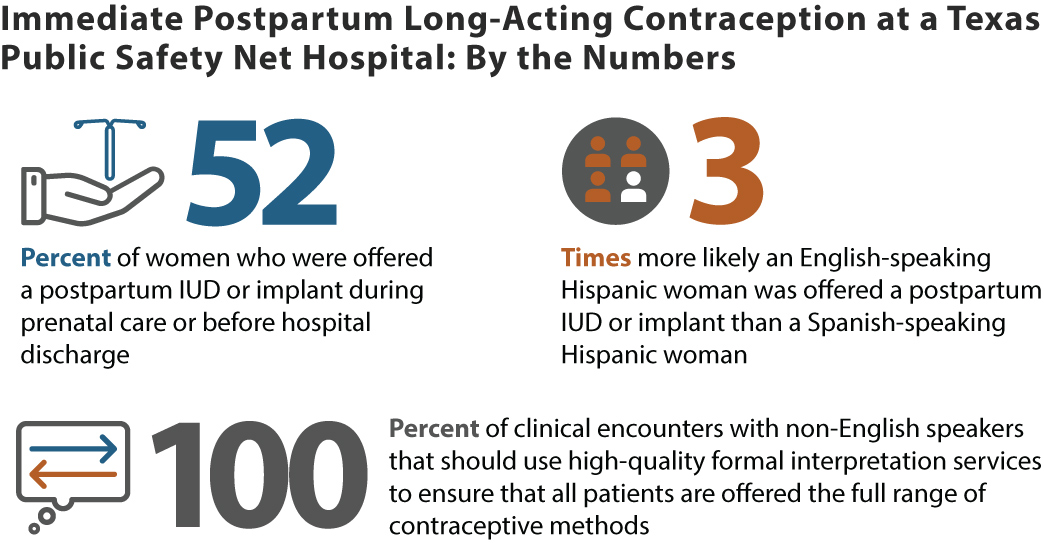

The average fertility treatment cost without insurance ranges from $12,000 to $75,000 per treatment. This presents a significant barrier for many LGBTQ families, who are, on average, more likely to have lower incomes and less wealth than cis/het families. This means that LGBTQ families face heightened financial barriers from the get-go. Even if LGBTQ families choose not to follow the reproductive route, adoptions can cost upwards of $15,000 to $40,000 depending on the state.

LGBTQ families also face additional structural barriers, from donor/surrogate selection, to added testing, to increased FDA regulated wait-times for directed known donor sperm (6 months compared to no wait for a sexually intimate partners). And on top of these barriers, LGBTQ families must navigate a draconian legal maze as they seek to secure their family choices with individual legal protections to affirm parental rights, ensure various kinds of access and birth certificate recognitions, and correct parental genders. For families who desire to have three or more recognised parents, there may be no legal protections to ensure that all parties are recognised appropriately. All of these barriers are coupled with additonal challenges like finding a donor and/or surrogate, co-parent agreements, and increased fertility issues – as LGBTQ folks are more likely to start trying to conceive later in life and likely have engaged in substance use, both of which significantly affect fertility.

In March 2020, most fertility clinics closed their doors due to the risk of COVID, the lack of medical equipment/supplies, and the unknown risk of virus transmission through sperm. This was a devastating blow to many prospective parents planning to conceive during this time period. Every missed cycle was a missed chance to try for a child. I saw first-hand the effect this was having in my many ‘how to conceive’ support groups. I felt all my plans slipping away. I had waited so long to try to start a family. There was so much in my life it could not control from an uncertain job market, to publications, to finishing my PhD. Before COVID the choice to at least try to start a family felt in my grasp. So as an academic, I stepped back, critiqued the systems, and turned my frustration and fears into research. My co-author and I began compiling news stories and academic research to make sense of everything we were witnessing.

We found that in the U.S and many other countries, fertility clinics closed due to uncertainty about procedure safety and lack of medical equipment. While we support a brief initial closure, many closed for an extended period, citing fertility treatment as a ‘non-essential medical service’. Other clinics opened but did not take in new patients, forcing many prospective families, both cis/het and LGBTQ, to put their plans put on an indefinite hold. In addition to fertility center closures, prospective LGBTQ families uniquely had non-medicalised methods interrupted or halted.

Social distancing, lockdown, and travel laws meant that many people could not make the necessary connections to provide or receive biological materials. This affected lesbian couples who were unable to drive a state away to collect a sperm deposit, gay couples whose surrogate was in another country and barred from entering the U.S., and multi-parent families whose households were not allowed to meet – or felt it was too dangerous to meet – to try to conceive.

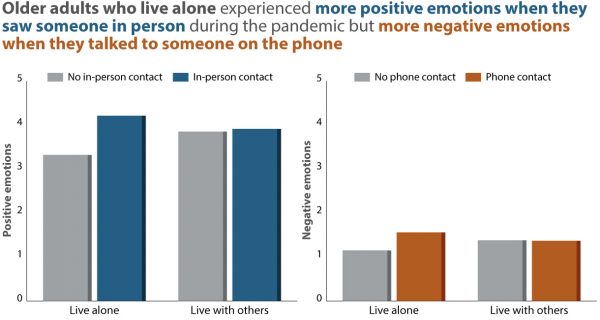

There were, of course, other effects as well. Recent research has shown that having fertility plans put on hold is psychologically equivalent to a miscarriage, and this situation is exacerbated when there is no definitive date to resume.

In the future, experts forecast that it’s not unlikely that we will encounter other pandemics over the coming years, or at the very least, a series of local and global disasters! Therefore, we have several recommendations that will benefit both LGBTQ families (and cis/het folks) facing infertility:

- Access to fertility treatments should not be deemed non-essential, which would include addressing the problem of medical gatekeeping to ensure that treatment is accessible to all who desire it.

- Federal guidelines for donor waiting periods should be significantly reduced or removed and replaced with an informed consent risk awareness procedures.

- Medical and insurance companies should redefine infertility as all families who cannot conceive without the aid of medical assistance.

- Federal aid should be enacted that reduces the inequality widening effects of the pandemic.

In addition, many folks are still banned from traveling, continuing the wait for many. We also recommend that governments, now with increased testing and vaccines, provide the possibility for people to travel to see family (broadly defined).

My story has a happy ending, for which I’m deeply grateful, given the barriers I’ve cited above that affect so many LGBQT+ folks. During the height of the pandemic, my wife and I were privileged to fly to my home country of England. With the help of Steffan and his wife Laura, we created our tiny human. Avril was born almost one year later in April 2021.

Penny Harvey is an assistant professor of human sexuality studies at the California Institute of Integral Studies. They research gender, sexuality, health, culture, and media. They can be reached at Pharvey@ciis.edu

Link to full article here Harvey & Ingraham, 2021