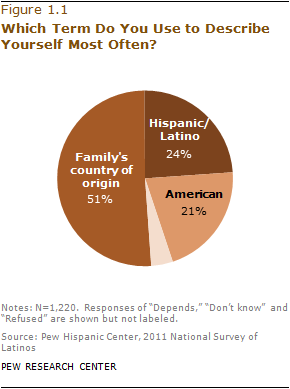

In 1970, the U.S. Census added a “country of origin” question to its demographics section, which asks respondents if they are “of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin.” But a new Pew Hispanic Center report indicates that, while these might be the official terms for those from Spanish-speaking countries and/or Latin America, they aren’t the preferred or most popular labels among those they’re supposed to identify. Only about 1 in 4 use the terms Hispanic or Latino most frequently to describe themselves:

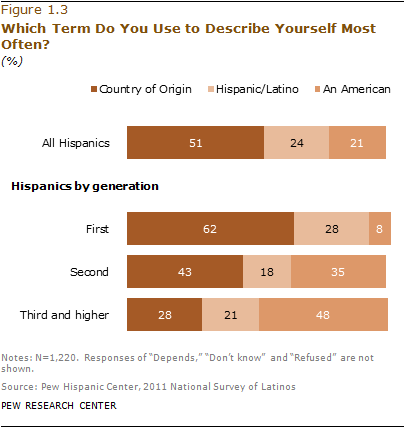

Not surprisingly, identification with different labels differs among recent immigrants and those born in the U.S. Among the first generation, country of origin is the overwhelming preference, but by the third generation, just over 1 in 4 choose that as their most common self-identifier:

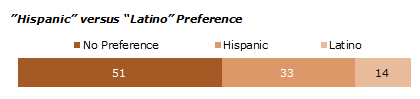

Most respondents had no preference between the terms Hispanic or Latino, but for those who did, Hispanic was more popular:

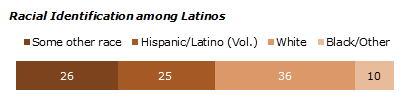

White was the most commonly-chosen racial identification:

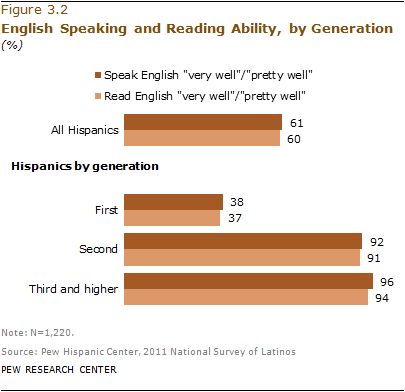

Most respondents also said that while they think it’s important that Hispanics be able to speak Spanish in the U.S., that learning English is very important for success. By the second generation, almost all rate themselves as knowing English “pretty” or “very” well:

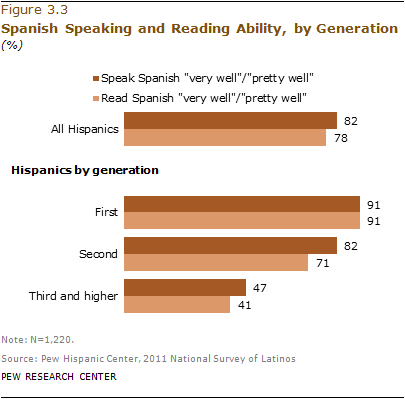

Conversely, among third-generation Hispanics, under half say they speak or read Spanish equally well:

Check out the full report for tons of additional information on identification, language use, etc.