Both men and women face a lot of pressure to perform masculinity and femininity respectively. But, ironically, people who rigidly conform to rules about gender, those who enact perfect performances of masculinity or femininity, are often the butt of jokes. Many of us, for example, think the male body builder is kind of gross; we suspect that he may be compensating for something, dumb like a rock, or even narcissistic. Likewise, when we see a bleach blond teetering in stilettos and pulling up her strapless mini, many of us think she must be stupid and shallow, with nothing between her ears but fashion tips.

The fact that we live in a world where there are different expectations for men’s and women’s behavior, in other words, doesn’t mean that we’re just robots acting out those expectations. We actually tend to mock slavish adherence to those rules, even as we carefully negotiate them (breaking some rules, but not too many, and not the really important ones).

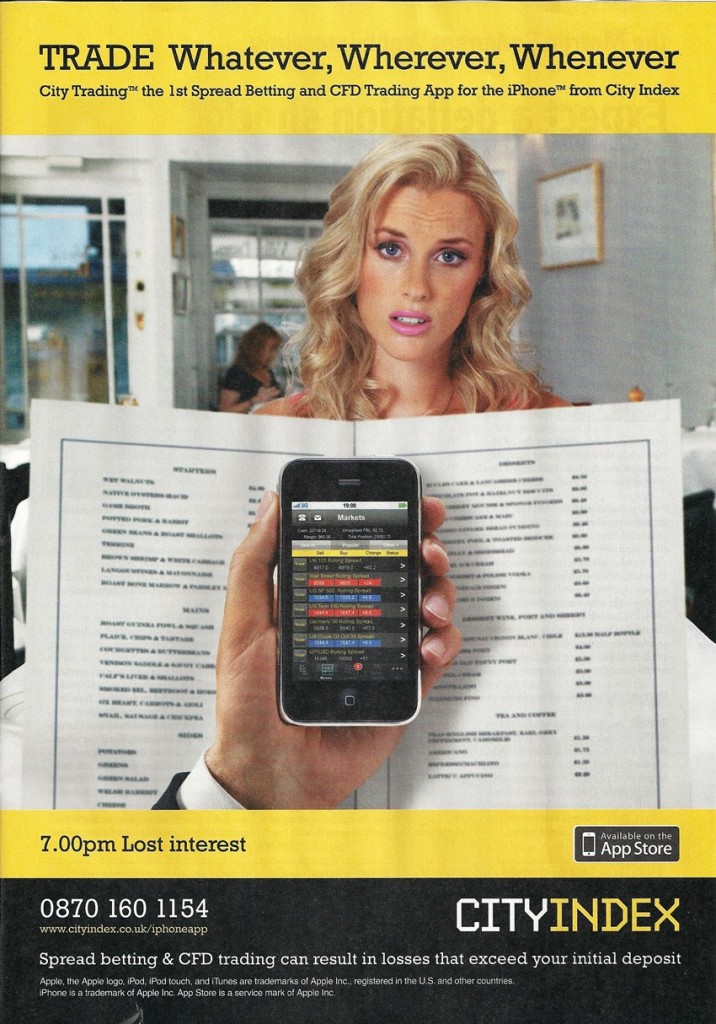

In any case, I thought of this when I saw this ad. The woman at the other end of the table is doing (at least some version of) femininity flawlessly. The hair is perfect, her lips exactly the right shade of pink, her shoulders are bare. But… it isn’t enough. The man behind the menu has “lost interest.”

It’s unfortunate that we spend so much time telling women that the most important thing about them is that they conform to expectations of feminine beauty when, in reality, living up to those expectations means performing an identity that we disdain.

We do it to men, too. We expect guys to be strictly masculine, and when they turn out to be jocks and frat boys, we wonder why they can’t be nicer or more well-rounded.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

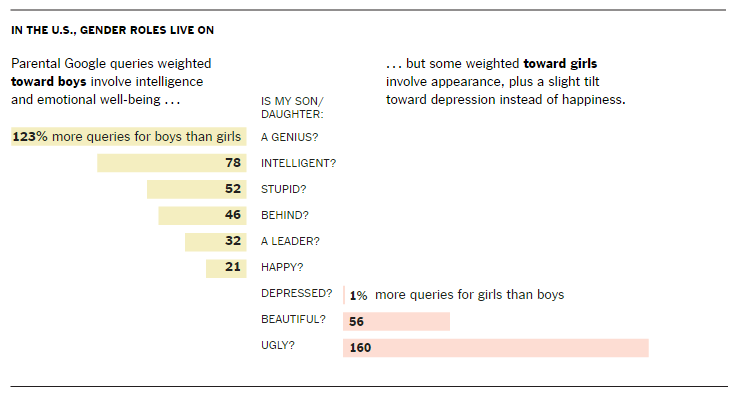

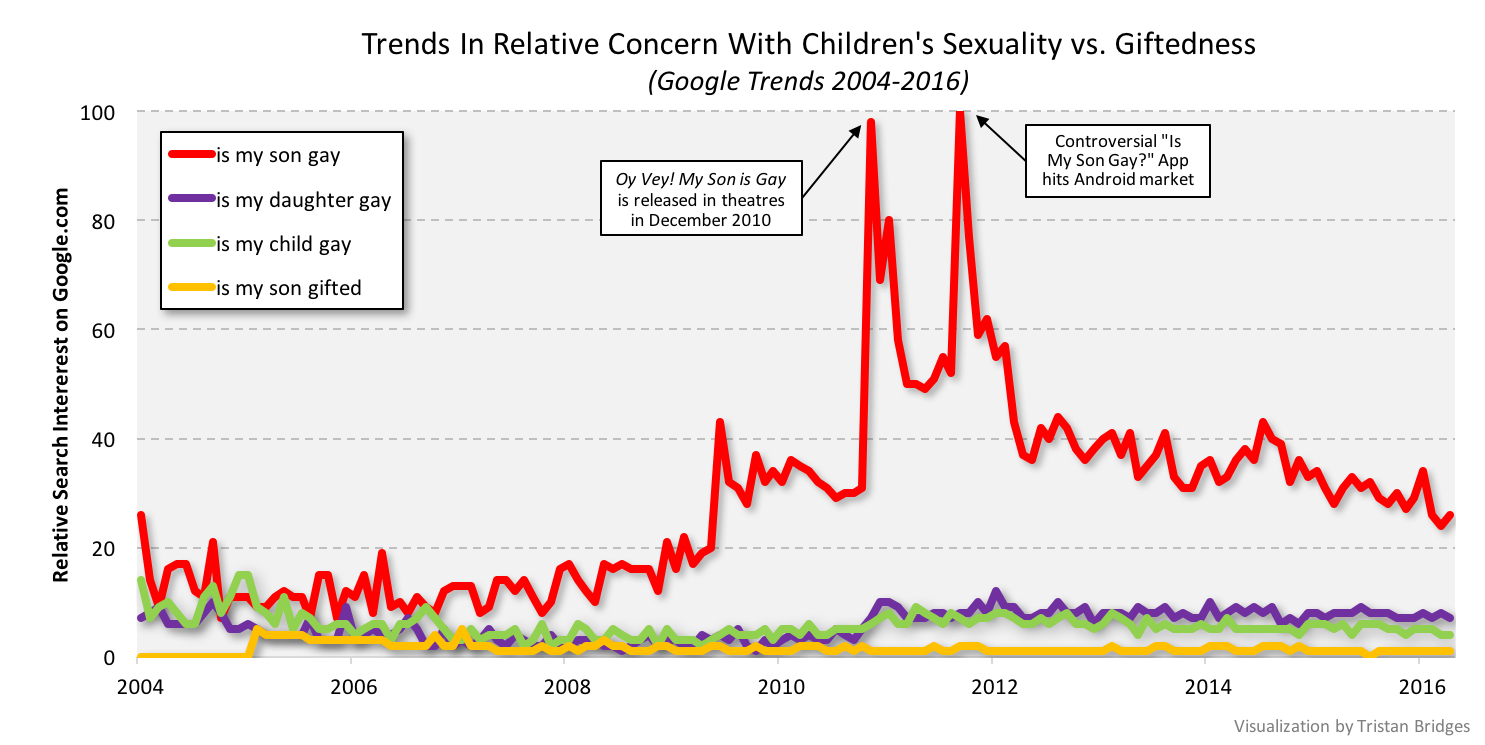

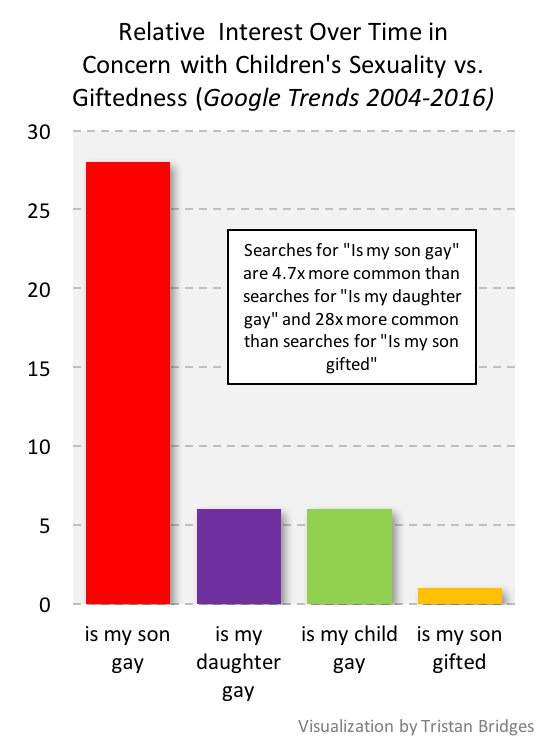

Indeed, over the period of time illustrated here, people were 28x more likely to search for “is my son gay” than they were for “is my son gifted.” And searches for “is my son gay” were 4.7x more common than searches for “is my daughter gay.”

Indeed, over the period of time illustrated here, people were 28x more likely to search for “is my son gay” than they were for “is my son gifted.” And searches for “is my son gay” were 4.7x more common than searches for “is my daughter gay.”