The 2020 Summer Olympics will be held in Japan. And when the prime minister of Japan, Shinzo Abe, made this public at the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, he did so in an interesting way. He was standing atop a giant “warp pipe” dressed as Super Mario. I’m trying to imagine the U.S. equivalent. Can you imagine the president of the United States standing atop the golden arches, dressed as Ronald McDonald, telling the world that we’d be hosting some international event?

Prime minister Abe was able to do this because Mario is a cultural icon recognized around the world. That Italian-American plumber from Brooklyn created in Japan is truly a global citizen. The Economist recently published an essay on how Mario became known around the world.

Mario is a great example of a process sociologists call cultural globalization. This is a more general social process whereby ideas, meanings, and values are shared on a global level in a way that intensifies social relations. And Japan’s prime minister knew this. Shinzo Abe didn’t dress as Mario to simply sell more Nintendo games. I’m sure it didn’t hurt sales. In fact, in the past decade alone, Super Mario may account for up to one third of the software sales by Nintendo. More than 500 million copies of games in which Mario is featured circulate worldwide. But, Japan selected Mario because he’s an illustration of technological and artistic innovations for which the Japanese economy is internationally known. And beyond this, Mario is also an identity known around the world because of his simple association with the same human sentiment—joy. He intensifies our connections to one another. You can imagine people at the ceremony in Rio de Janeiro laughing along with audience members from different countries who might not speak the same language, but were able to point, smile, and share a moment together during the prime minister’s performance. A short, pudgy, mustached, working-class, Italian-American character is a small representation of that shared sentiment and pursuit. This intensification of human connection, however, comes at a cost.

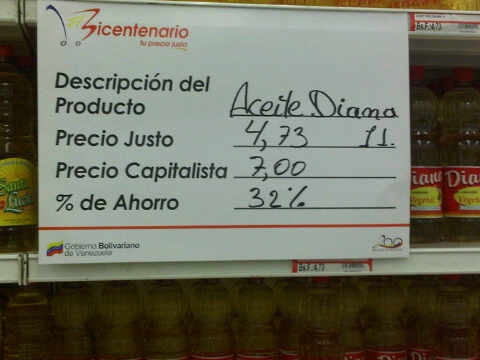

We may be more connected through Mario, but that connection takes place within a global capitalist economy. In fact, Wisecrack produced a great short animation using Mario to explain Marxism and the inequalities Marx saw as inherent within capitalist economies. Cultural globalization has more sinister sides as well, as it also has to do with global cultural hegemony. Local culture is increasingly swallowed up. We may very well be more internationally connected. But the objects and ideas that get disseminated are not disseminated on an equal playing field. And while the smiles we all share when we connect with Mario and his antics are similar, the political and economic benefits associated with those shared smirks are not equally distributed around the world. Indeed, the character of Mario is partially so well-known because he happened to be created in a nation with a dominant capitalist economy. Add to that that the character himself hails from another globally dominant nation–the U.S. The culture in which he emerged made his a story we’d all be much more likely to hear.

We may be more connected through Mario, but that connection takes place within a global capitalist economy. In fact, Wisecrack produced a great short animation using Mario to explain Marxism and the inequalities Marx saw as inherent within capitalist economies. Cultural globalization has more sinister sides as well, as it also has to do with global cultural hegemony. Local culture is increasingly swallowed up. We may very well be more internationally connected. But the objects and ideas that get disseminated are not disseminated on an equal playing field. And while the smiles we all share when we connect with Mario and his antics are similar, the political and economic benefits associated with those shared smirks are not equally distributed around the world. Indeed, the character of Mario is partially so well-known because he happened to be created in a nation with a dominant capitalist economy. Add to that that the character himself hails from another globally dominant nation–the U.S. The culture in which he emerged made his a story we’d all be much more likely to hear.

Tristan Bridges, PhD is a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He is the co-editor of Exploring Masculinities: Identity, Inequality, Inequality, and Change with C.J. Pascoe and studies gender and sexual identity and inequality. You can follow him on Twitter here. Tristan also blogs regularly at Inequality by (Interior) Design.