By: C.J. Pascoe and Tristan Bridges

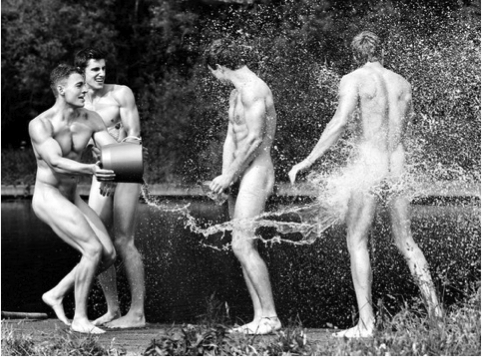

What it means to be masculine changes over time and from place to place. After all, men used to wear dresses and high heels, take intimate pictures with one another and wear pink in childhood. In our scholarship and blog posts we have been grappling with making sense of some of these more recent changes as we’ve watched (and contributed to) a discussion about what it means to be an ally and changing views on gender and sexual inequality—primarily among men (see here and here). We recently published an article thinking through changes in contemporary definitions of masculinity allegedly occurring among a specific population of young, white, heterosexual men.

What it means to be masculine changes over time and from place to place. After all, men used to wear dresses and high heels, take intimate pictures with one another and wear pink in childhood. In our scholarship and blog posts we have been grappling with making sense of some of these more recent changes as we’ve watched (and contributed to) a discussion about what it means to be an ally and changing views on gender and sexual inequality—primarily among men (see here and here). We recently published an article thinking through changes in contemporary definitions of masculinity allegedly occurring among a specific population of young, white, heterosexual men.

We sought to make sense of some complex issues like the contradiction between what seems like an “epidemic” of homophobic bullying alongside rising levels of support for gay marriage. Or the seeming contradiction between young white men’s adoration and emulation of hip hop culture side by side with deeply entrenched racism toward African-American men. Or the way in which contemporary men speak of desiring equal partnerships and marriages, yet women still earn less in the workplace and do more of the housework and childcare.

In our article, we collect a body of research illustrating that, often, what is going on in contradictions like this, is that systems of power and inequality are symbolically upheld even as their material bases are (partially) challenged (e.g., here). We show how these seemingly disparate issues might be better understood as small pieces of a larger phenomenon—something we refer to as “hybrid masculinity” (drawing on other scholars—see here, here, and here).

Hybrid masculinity refers to the way in which contemporary men draw on “bits and pieces” of feminized or marginalized masculine identities and incorporate them into their own gender identities. Simply put, men are behaving differently, taking on politics and perspectives that might have been understood as emasculating a generation ago that seem to bolster (some) men’s masculinities today. Importantly, however, we argue that research shows that this is most often happening in ways that don’t actually fundamentally alter gender and sexual inequality or masculine dominance. In other words, what recognizing hybrid masculinity allows us to do is to think through these changes in masculinity carefully. While these changes may appear to challenge gender and sexual inequality, we argue that most research reveals that hybrid masculinities are better understood as obscuring than as challenging inequality.