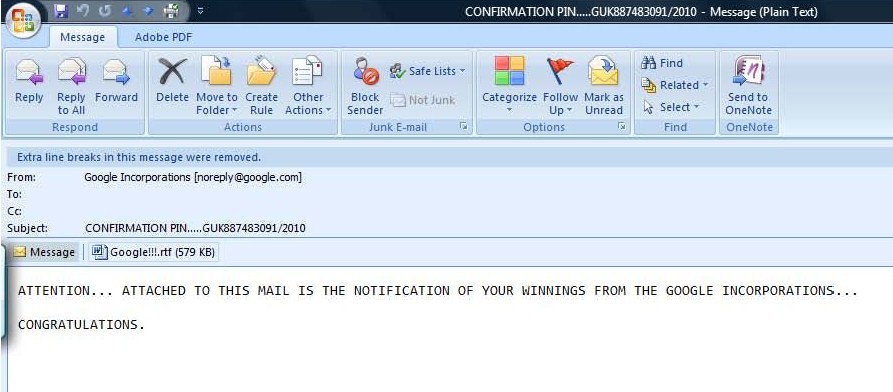

O frabjous day! ZOMG, I WIN TEH INTERNETZ!!!

Have you gotten a flurry of these things as well? Emails of an exuberantly preposterous nature, full of rip-snorters that make you wonder how the authors managed to create such a sublime pastiche of accurate and absurd, plausible and im-?

Apparently, there are LOTS of other “winners.” And thanks to the many websites that seek to expose internet scams, it’s possible to read several versions of this email. Reading across versions allows several interesting patterns emerge.

Scam Emails as a Literary Genre

On the one hand, it suggests that scam letters can be read as a kind of literary form in their own right—an insight, I’m happy to say, that has been offered by others, notably Scam-O-Rama, which notes that scammers’ missives “smack of political satire, [and] contain elements harking back to 19th century literature.” If you can get past the jarring confusion about the words “Corporation” and “Incorporation” (plus the random plural added to the latter), the authors of the “Google Incorporations” series have a virtually Dickensian flair, from the names they invent for the letters’ authors to their conceits about why and how Google is distributing its largesse.

Two literary aspects of the letters stood out to me:

- The names

Most versions of the letter are putatively authored by someone bearing the title of “Doctor.” Whether this is supposed to connote a medical credential or a doctorate is unclear—that’s part and parcel of the strategic ambiguity employed throughout the letters. The names themselves range from the mundane (“Dr. Frank Smith” or “Dr. Nelson Cole”) to the more memorable (“Dr. Kibbs Richardson”). One particularly flamboyant letter is authored by a certain “Sir Richard Scholes,” purportedly the “Foreign Transfer Manager” for Google. Because of course a British lord would occupy a middle management position at an American high tech company. My personal favorite is “Dr. Paul Zimmaman”—written as if by a person who has never seen “Zimmerman” written out, but has heard the name spoken and just spelled it as it sounded.

- The vocabulary

This seems to be one of the defining characteristics of SPAM “literature” in all genres, not just the “Google Incorporations” series. For whatever reason, scammers just love the word “hence.” As in “Hence we do believe with your winning prize, you will continue to be active and patronage to the Google search engine.” So that’s -1 for inability to distinguish between a noun and a verb (“patronage”), but +1 for the “Hence”?Running a close second is the word “therefore,” as in “You have therefore won the entire sum of ?450,000.00 {Four Hundred And Fifty Thousand Great British Pounds Sterling} and also a certificate of prize claims will be sent along side your winning cheque.” A certificate! Making things even more official!Making things seem official is the name of the game: for instance, you aren’t just asked how you want to get your money, you have to “select your mode of prize remittance.” Prolixity FTW!

Global Capitalism as Seen from the Periphery

Secondly, the “Google Incorporations” letters can be read from a more sociologically analytical standpoint, for what they tell us about the mental models some people hold of the contemporary global economy. In this sense, the letters can be savored both as unintentional comedy and as commentary on how capitalism is understood in some parts of the world.

The assumptions underlying the “Google Incorporations” series are revealing as accounts that the authors think will be plausible to readers (e.g., potential victims or “marks”). Obviously, the authors know that Google isn’t giving away money, but they’re hoping to create a convincing illusion.

My interest lies here: the pastiche of capitalism that the scammers are producing. What features do they consider indispensible to creating that illusion? The many ways in which they fail to portray corporate activity realistically are glaringly obvious. But I’m interested in what they think is going to fly with readers—at least well enough to get readers to cough up the personal data the scammers are seeking.

- Spatial indeterminacy

Google’s geographical location turns out to be one of the things that the scam letters’ authors don’t consider very important to making their appeals convincing. Mimicking a standard business letter, the Google Incorporations “award notification” leads with the firm’s address. But the address is in the UK! -

Google Incorporations.

Stamford New Road,

Altrincham Cheshire,

WA14 1EP

London,

United Kingdom.Leaving aside the plausibility problem of situating one of the world’s leading tech firms in the UK rather than the Silicon Valley, the authors apparently don’t have a very good grip on English geography.While there is actually a Stamford New Road in the town of Altrincham, Cheshire, that town is several hundred miles northwest of London.

It looks to me as if the authors just randomly added “London” between the postcode and the country name, much as they added the random “s” at the end of the word “Incorporation.” Because dropping the name of the international capital of finance can only help, amirite?

Call it an excess of creative exuberance. Or the scam equivalent of gilding the lily. The same impulse that made Dennis Kozlowski buy the $15,000 umbrella stand.

- The prize giveaway: corporations as cargo cults

Here’s where things really get interesting, in my view.In the world of the “Google Incorporations” authors, corporations are mysterious entities that dispense large chunks of money on a whim. A sum approaching three-quarters of a million US dollars just to “thank” loyal customers? No problemo!Adding to the mirth, the give-aways are purported to occur via lottery—a lottery that “winners” never entered in the first place. It makes the corporate world seem like a kind of modern cargo cult, dumping wealth haphazardly upon the unsuspecting.

A cargo cult, as Wikipedia informs us,

“is a religious practice that has appeared in many traditional tribal societies in the wake of interaction with technologically advanced cultures. The cults focus on obtaining the material wealth (the “cargo”) of the advanced culture through magic and religious rituals and practices. Cult members believe that the wealth was intended for them by their deities and ancestors.”

The cargo cult originated in Melanesia, where planes would drop cartons of food and so forth from the sky, much to the surprise of the local population. New beliefs sprung up around this experience, along with new rituals designed to get the mysterious flying objects to come back and dispense more wealth.

In a way, this is a very sensible interpretation of capitalism: people get rich, seemingly at random. It’s as if money just drops out of the sky onto their heads.

The premise of the “Google Incorporations” letter—and, I would argue, lotteries in general—can be summed up by the idea “it could happen to you, too!”

This wistful thought may explain why so many people ignore the obvious signs that these “award notifications” are frauds, and post to scam-exposé websites, asking plaintively whether the offers could possibly be legit. It’s all very reminiscent of Pearl Bailey’s appeal to Santa for a “Five Pound Box of Money:”