Behavioral finance has exploded in popularity not just because it’s interesting—regular finance is interesting, too—but because it combines that interest factor with an abundance of what one scholar called “descriptive charm.”

There is something strangely entertaining in reading about the economic foibles of others: one part schadenfreude, plus one part abashed recognition of one’s own past mistakes—mixed with quiet relief to find oneself with lots of company in making those mistakes.

Plus, it gives many of us readers great stories that to tell at dinner parties. Being able to talk about the myth of the “hot hand” in basketball, or investor preferences for cash versus stock dividends, can make for a pretty entertaining evening in some circles.

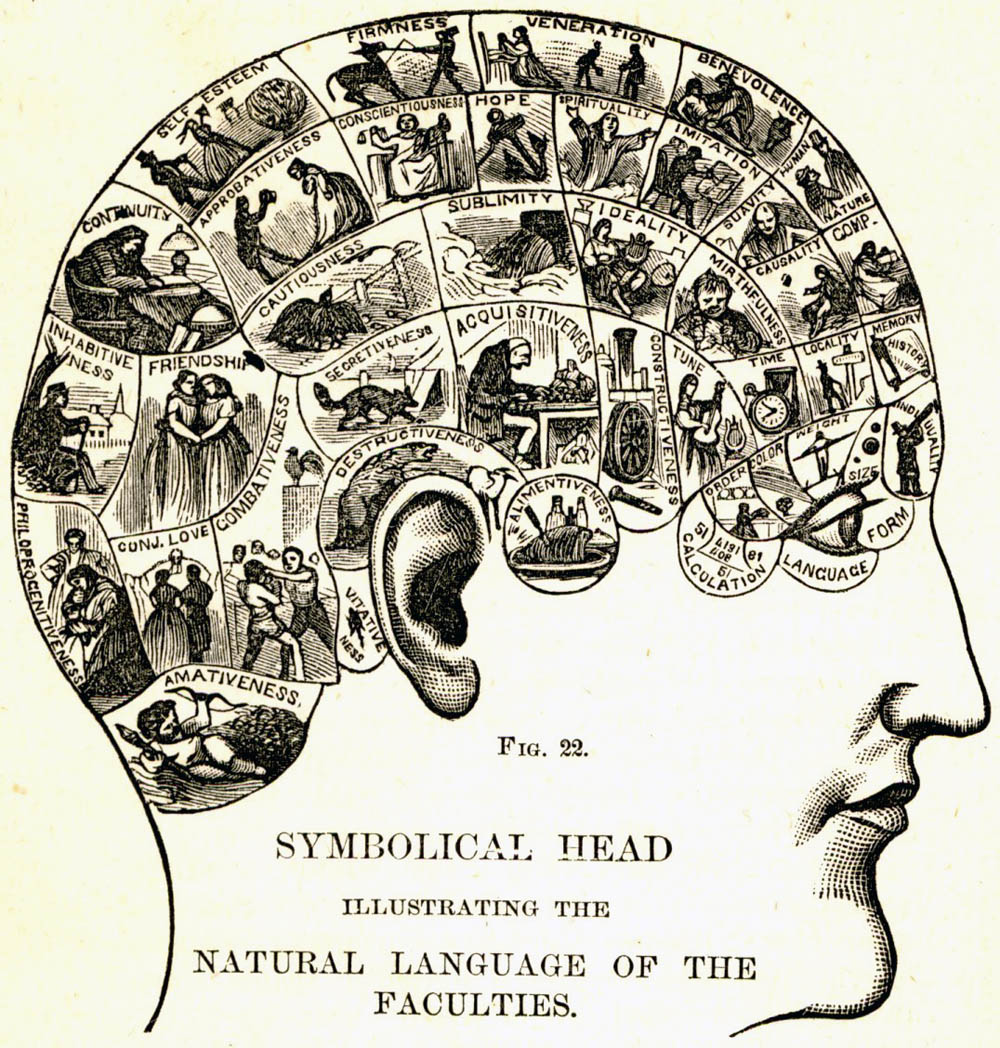

Reading behavioral finance can also provides a sense of Finally Understanding How Things Work when it comes to money and markets. Learning about common cognitive errors in economic decision making, such as “anchoring,” and “availability bias,” feels like getting a peek inside the flawed machines that are our brains, making it seem possible to predict the behavior (particularly the mistakes) of others, and guard against them in oneself. In short, behavioral finance seems to offer insight and a sense of control, imposing order on what otherwise appears chaotic and unpredictable.

But a dozen years after my own personal infatuation with behavioral finance began—by devouring Richard Thaler‘s classics, Advances in Behavioral Finance and The Winner’s Curse—a number of limitations have become obvious.

All research programs have limitations, of course. But those of behavioral finance undermine its purpose: that is, to enhance understanding of financial markets and investor behavior. Others have written eloquently on this subject, particularly Daniel Beunza and David Stark, and John Y. Campbell. What I have to add to this ongoing debate boils down to two points and their consequences:

- 1. Failure to acknowledge the findings of the allied social sciences

One of the cardinal laws in scholarship is to acknowledge the work of others and avoid reinventing the wheel. But when you read works of behavioral finance, you’d never know that deviations from rational, self-maximizing behavior are old news in psychology, political science, sociology and anthropology. Check the references section of a behavioral finance article or book and see how many citations from those fields you can find. Chances are, there will be zero. Behavioral finance scholars generally cite each other, or work from mainstream economics and finance.

This is particularly strange since so much of contemporary behavioral finance depends on the contributions of social psychologists like Daniel Kahneman (a 2002 Nobel laureate for his work in behavioral finance) and the late Amos Tversky, as well as much older work by people like Herb Simon, who was a Professor of Political Science and Industrial Administration at various points in his career. Simon won the Nobel Prize in economics for work done half a century ago on “bounded rationality“—a concept closely tied to many of the key phenomena examined by behavioral finance, but which is virtually ignored in their publications.

While a lot of academic research speaks to a rather small group of other academics, behavioral finance is distinctive within the social sciences for restricting its scholarly conversation so tightly. This isn’t the case in the closely-related disciplines of economic sociology, neo-institutionalist political science, and economic anthropology, all of which regularly cite and engage with one another, to the enrichment of all.

In the case of behavioral finance, reluctance to acknowledge the many research interests it shares with the allied social sciences may be part of the larger project of rigid separation and boundary enforcement that has been carried out by economists since the time of Pareto. This has created what Schumpeter described as a regime of “mutual vituperation” which has kept economics and finance in a state of self-imposed incommunicado with sociology, limiting the advancement of knowledge on our shared interests. Behavioral finance, it seems, is sticking to the party line on this point.

- 2. A narrow, limited critique of economic theory

Cataloging the many ways humans fail to think rationally about money, investments and risk is a good start. But in most ways, behavioral finance leaves intact the problematic assumptions of traditional finance, pulling its punches, so to speak. Among the most noteworthy examples:

- a. Behavioral finance remains stuck at the individual level of analysis

As in traditional finance and economics, the object of inquiry in behavioral finance is the individual—despite rafts of evidence going back decades that individuals don’t make decisions about money, risk or investing in a vacuum, but as a result of social influences. Of course, this evidence comes from those allied social sciences that are being so studiously ignored. For example, economic psychologist George Katona showed 35 years ago that most people choose investments based on word of mouth recommendations from their friends and neighbors. This influence of social forces in economic decision-making has been demonstrated with equal or greater impact among finance professionals—for instance, in a study of Wall Street pension fund managers by economic anthropologists O’Barr and Conley, and more recently in a sociological study of arbitrage traders by Beunza and Stark.

In the past, there were encouraging signs that behavioral finance might break through the limitations imposed by sticking to the individual level of analysis, most strikingly in Robert Shiller’s 1993 statement that “Investing in speculative assets is a social activity.” But thus far, the implications of such statements, and the plethora of evidence supporting them, remain unexplored.

- b. Behavioral finance limits itself to pointing out failures of cognition and calculation

As important as those factors are in distorting financial decision-making, there are a host of others that we know about—based on research in those allied social sciences that behavioral finance doesn’t acknowledge—that are excluded from research in behavioral finance. This includes emotions, and social phenomena like status competition, both of which play a significant role in the findings of economic sociology, psychology and anthropology. The cognitive/calculative failures may interact with the socio-emotional phenomena, but we won’t know as long as behavioral finance pretends the latter don’t exist. That’s a loss for all of us interested in markets, money and investing.

- c. Behavioral finance doesn’t explain how individual acts and decisions produce aggregate outcomes

As a consequence of keeping the analytical focus on individuals—avoiding the social and interactive aspects of economic activity—behavioral finance doesn’t have the theoretical means to address mechanisms through which individual acts and decisions aggregate. That means it can’t explain institutions and other manifestations of collective behavior which form the context for all the individual behavior it examines. Of course behavioral finance can’t answer all questions about money and markets, but it ought to be able to explain what happens when hundreds, or hundreds of millions, of people fall prey to the “hot hand” fallacy or availability bias? If behavioral finance won’t touch questions like that, who will?

The consequences for ignoring the other social sciences and mounting a very narrow critique of traditional finance and economics, include:

- Limited predictive power

Behavioral finance tells us more about what people won’t do (e.g., behave according to notions of rationality outlined in economic theory) than what they will do.

- Contradictory implications

Are investors risk-averse or overconfident? How should we reconcile seemingly contradictory findings like these? Behavioral finance doesn’t tell us, because of its…

- Failure to offer a viable alternative to the theories it challenges

Pointing out all the ways that real life behavior doesn’t bear out the predictions of traditional economics and finance is interesting—even fascinating, at times—but it’s not an alternative theory. “People aren’t rational” isn’t a theory: it’s an empirical observation. An alternative theory would need to offer an explanation, including causal processes, underlying mechanisms and testable propositions.

All this keeps behavioral finance dependent on traditional economics and finance rather than allowing it to grow into a robust theoretical realm in its own right. Perhaps someday the field will develop into something more truly challenging to economic orthodoxy. Until then, behavioral finance will have to play Statler and Waldorf to the Muppet Show of mainstream finance—providing entertaining critique, but not replacing the marquee acts. (Now if economics would just substitute Milton Berle for Milton Friedman….)