The story emerged for me two Thursdays ago, when a colleague at the University of Missouri, where I work, asked if I wanted to accompany her to find a march in support of Jonathan Butler, a graduate student on hunger strike with demands that president Tim Wolfe resign over his inaction towards racism on campus. We encountered the protest as it moved out of the bookstore and followed it into the Memorial Union, where many students eat lunch. This was the point at which I joined the march and stuck with it across campus, into Jesse Hall, and finally to Concerned Student 1950’s encampment on the quad where the march concluded. Since then I’ve been trying to read up on what led up to this march, sharing what I find as I go. This task became much easier after Wolfe’s announcement on Monday that he would resign, and the national media frenzy that followed. At first, however, learning about the march that I had participated in proved far more difficult than I expected.

Once a story becomes national, journalists collate the facts and package them into a consumable narrative. Prior to that, however, interested parties have to scour a complex and fragmented landscape to answer a deceptively simple question: what’s going on here? This is because “news” is no longer the exclusive purview of corporate media conglomerates, or even local ones, but moves – or transmediates – through an ecology of personal networks, digital platforms, and large and small media organizations.

For example, local news coverage of the protests – and, save for the story earlier this year of Mizzou student body president Payton Head’s encounters with hate speech, it seemed all coverage was local or regional within my state – alluded to the incidents that contributed to the unfolding events, but didn’t provide an easy thread to follow. Butler and Concerned Student 1950’s list of demands were referenced in many local news stories, but not in their entirety and without links to the full list of demands. Social media was similarly fragmentary, but Jonathan Butler’s Twitter and Facebook accounts (where he reposted an open letter to the university administration and the list of demands) helped clarify some things. The difficulty of following a story when it is still largely local seems like a well known problem. It was a problem in Ferguson early on, and as a lifelong resident of Columbia observing and participating directly in the protests, the problem really hit home for me again this week.

An exhaustive timeline that could capture the details became a daunting task. In what follows, I recount the story as I encountered it, through local press, national media, from Jonathan Butler’s public correspondence on social media, and friends involved with Butler’s/Concerned Student 1950’s protests.

- In September, Mizzou student body president, Payton Head, was accosted with racial slurs on campus. Head recalled the incident in a Facebook post, which eventually went viral and garnered national attention. I heard this story through my coworker friend who would eventually invite me to the march.

- Weeks later, Concerned Student 1950, a group of students named after the year the first black student was admitted to MU, blocked UM System President Tim Wolfe’s car during the homecoming parade, in protest of MU’s inaction to address recent instances of racism (including Head’s) experienced on campus. I went to the parade to follow a march organized by local churches and the community group Race Matters advocating diversity and inclusion, but didn’t learn of Concerned Student 1950’s separate encounter with UM President Tim Wolfe until days later.

- New UM Chancellor, R. Bowen Loftin, released a statement denouncing “incidents of bias and discrimination on and off campus.” This was followed by a campus wide announcement of the development of mandatory diversity and inclusion training. I and everyone else at the University received an email of the announcement.

- Fast forward to the week before last, when my coworker friend mentioned that Jonathan Butler, a Mizzou graduate student, went on hunger strike in protest of UM System’s negligence to meaningfully address harassment targeting racial and religious minorities on campus, including but not limited to a swastika drawn in feces on a bathroom wall and racial slurs launched at the Legion of Black Collegians. Tim Wolfe’s silence at the homecoming parade was also noted.

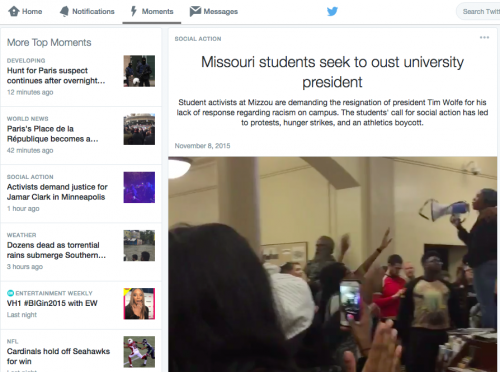

- On that Thursday (November 5th), Concerned Student 1950 held a demonstration in support of Butler’s hunger strike (then in its 4th day without an official response) protesting UM System’s insufficient response to the aforementioned acts of harassment and Tim Wolfe’s continued silence on the matter. The demonstration involved a march through campus, with stops at key administrative and symbolic centers.

The march left me with a lot of questions. Searching our local newspapers’ websites, most reports focused on Butler’s hunger strike, but only made passing reference to Concerned Student 1950’s list of demands (I found them eventually, in a PDF linked at the bottom of a story.) At this point I gave up searching news reports and looked up Jonathan Butler on Twitter. There he’d posted the list of demands and letter to UM President Wolfe, which promised direct action if their demands weren’t met by October 28.

Butler’s Twitter and Facebook accounts became primary sources for Concerned Student 1950’s public communications. Through them I learned of more stories of harassment on campus, in-person slurs and anonymous slander from Yik Yak among them, and stumbled upon a link to an informative timeline at The Maneater, MU’s independent student press. The timeline mentioned additional contributing events, from the graduate student walkout following the University’s failure to meet their demands for permanent reinstatement of graduate health benefits; to MU’s discontinuation of refer and follow privileges and the ensuing Pink Out Day protest to reinstate them along with Planned Parenthood partnerships; Racism Lives Here rallies; and a sit-in at Jesse Hall.

At the beginning of my inquiry into this story, finding a smoking gun around the corner felt inevitable, but in the course of tracing the events, the more it appeared like death by a thousand unaddressed cuts. Local media’s and social media’s fragmentary qualities only exacerbated this impression, which was further complicated by the fact that much of the news broke first on personal social media accounts:

- The march was livestreamed by local media, footage that has since disappeared. Video I shared on Snapchat has of course evaporated. (Note to self: remember to hit the save button on your snaps next time you join a march.)

- Video of (now former) UM System President Wolfe’s dismissive response to activists after a fundraiser in Kansas City was shared directly by protesters on Twitter.

- The announcement by black Mizzou football players of their strike was made in a tweet, as was the announcement of solidarity from the full team and Coach Pinkel.

- Many counter-protest comments and later death threats, which included a direct quote from a comment left by the shooter involved in the Oregon college shooting in October, surfaced on Yik Yak.

By the time Wolfe and Chancellor Loftin had resigned on Monday and Butler’s hunger strike came to an end, local, regional, national, and citizen media was descending, in its various corporeal-social media forms, upon Concerned Student 1950’s campsite at Mizzou. While the fact that individual reporters would eventually come to clash with the student activists being documented may not be surprising, understanding the dynamics propelling this documentation point to the heightened stakes of media representation and the contested ground they signify for radical social movements.

In this twist in the story (‘twist’ in the sense of a recurring trope in protest documentation) that finds overzealous documenters rebuffed by protesters — and the free speech extremism that ensued — is important not only as a tale of actual ethics in journalism (or the lack thereof), but also about the effects of the attentional economy and what it rewards and reinforces for the media(s) that indulge it. The drive to collate the facts of a story and package them into a familiar narrative imminently consumable by a mass audience has common and uncontroversial costs, e.g. simplifications, mischaracterizations, and outright lies. However, while there’s plenty to debunk in news reports, it’s arguably in the framing of coverage, within individual reports but especially in the kinds of stories media outlets choose to spotlight, that breeds the greatest misrepresentations. Whether such attention-oriented coverage ultimately raises public awareness of these incidents (and occasionally their underlying social/structural origins) that otherwise might have remained invisible to a national/international audience, the price of this visibility is more often than not a decontextualized view from nowhere.

Here the students’/faculty’s attempts to create space between themselves and the journalists documenting their activity could be understood, I argue, as the Movement trying to exercise a degree of control over the construction of its own narrative against readily shareable (viral) packaging. The implications of this struggle for narrative control might also be instructive for an alternative to the current national (oversimplified)/local (underdeveloped) media dichotomy. An alternative system that afforded members of a community or a specific movement the ability to package their narrative for consumption by outsiders (who may still be locals) would be a modest improvement. A more radical system, one that actively repelled or short circuited viral transmission by retaining the story’s necessary local context and details, could allow communities and movements to disperse their stories without sacrificing as much control of the narrative*, its local roots, and its recirculation by various media entities. What that looks like, though, deserves an essay of its own…stay tuned.

Nathan is invariably in medias res on Twitter.

* Perhaps part of the problem, as this essay argues, is in our tendency to impose a traditional, linear narrative onto phenomena witnessed in everyday life.