Immigration is a hot topic, especially with elections coming up. Donald Trump has called immigrants “rapists” and “criminals”, perpetuating anti-immigration rhetoric. Common immigration myths include that immigrants are taking Americans’ jobs, burden the economy, and refuse to speak English. The Washington Post covers a report written by a group of Harvard professors, led by sociologist Mary Waters.

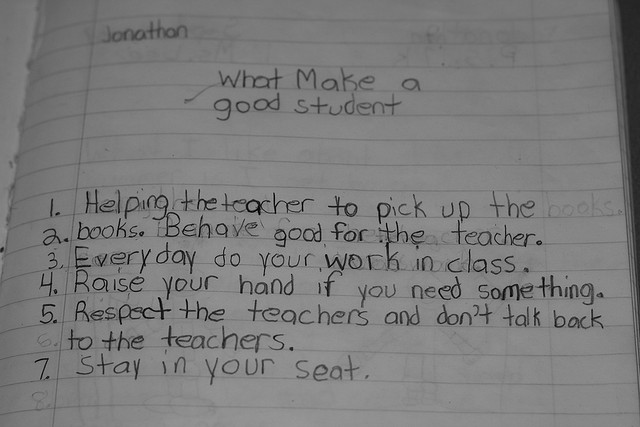

- “Immigrants are picking up English just as quickly as their predecessors”

In fact, today’s immigrants are learning English faster than their predecessors. This is partially due to how global English is, which means that immigrants are more likely to have been exposed to it or to have taken English classes already. Additionally, American schools are becoming better at teaching English to immigrant students.

- “Immigrants tend to have more education than before”

Historically, immigrants were low skilled workers from southern and eastern Europe in the early 1900s. Recently, however, immigrants are more likely to have four years of education on average. Approximately, 28% of recent immigrants hold a bachelor’s degree or higher, which is a 19% increase since 1980.

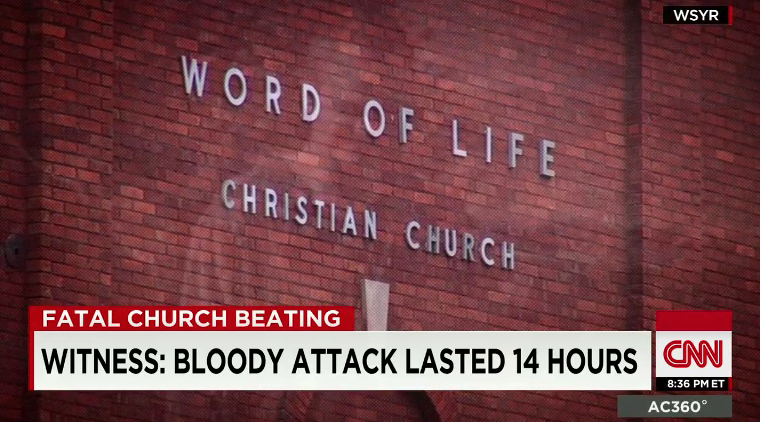

- “Immigrants are much less likely to commit crimes—but they soon learn”

In fact, immigrant neighborhoods are considered to be some of the safest neighborhoods as immigrants are least likely to commit crimes. Native-born men aged 18-39 are 5 times more likely to end up in jail than immigrants. While immigrants are initially fearful of picking up criminal influences, by the second and third generation, they are more likely to engage in criminal behavior.

- “Immigrants are more likely to have jobs than the native-born”

Immigrants are determined to find employment, and they are more likely to be employed than their native-born counterparts. Between 2003-2013, 86% immigrants were employed compared to 82-83% native-born Americans. This also holds true for men who have not earned a high-school diploma, where 84% immigrants are employed compared to 58% native-born Americans.

While the report combats common myths about immigration, it does not give a concrete answer as to whether today’s immigrants have the same opportunities as earlier generations of new Americans, despite being educated, staying away from crime, holding jobs, and paying taxes.