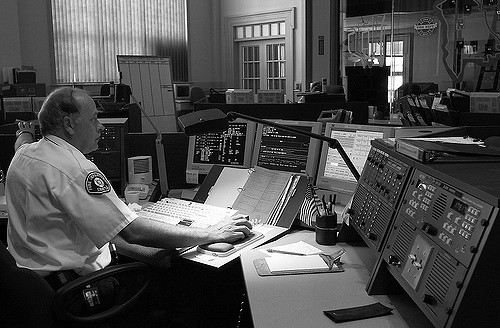

Surveillance technology dominates policing in many major cities, and software companies continue to develop tools that allow law enforcement to collect and analyze data on traffic violations, citizen complaints, and even license plate photographs. A recent CNN Tech article highlighted sociologist Sarah Brayne’s research on the Los Angeles Police Department’s use of one such data collection software, Palantir. Brayne’s findings suggest that while the utilization of big data in policing facilitates communication, it also raises some major concerns of privacy and potential bias.

With the help of Palantir, LAPD officers use a point system to measure the risk of individuals with extensive criminal records, awarding points for a variety of law infractions and police interactions. However, Brayne found that individuals from low-income communities of color are more likely to have their risk measured — she cautions that such systems can be cyclic, with more points leading to more police contact, and vice versa.

Another potential problem is that of privacy. Palantir has improved location tracking abilities and allows law enforcement to gather and connect more information about individuals than ever before, but this often includes information on individuals without police contact. Certainly there are clear benefits; sharing data can help connect related crimes and more information helps police to work more efficiently and effectively. But challenges arise as technology develops. Brayne warns,

“I’d caution against the thinking that if you have nothing to hide, you have nothing to fear. That logic rests on the assumption of the infallible state. It rests on the assumption that actors are entering information without error, prejudice or discretion.”

For more on the biases behind surveillance technologies, check out this TROT on computer code as free speech.