Parents often equate good parenting with spending as much time with their children as possible. The idea is that, in those hours, parents will cultivate particular characteristics in their children that will contribute to bright futures. But is helicopter parenting really worth it? Sociologists Melissa Milkie and Kei Nomaguchi share the findings of their recent study with the Washington Post: “I could literally show you 20 charts, and 19 of them would show no relationship between the amount of parents’ time and children’s outcomes. . . . Nada. Zippo,” says Milkie.

It’s not the number of hours, but quality of time spent together that matters. Interactive activities like reading to a child, sharing a meal, and talking one-on-one benefit kids, while just watching TV together may be detrimental, as Amy Hsin found. Still, Milkie and Nomaguchi’s study did find that teenagers who engaged with a parent for six hours per showed lower levels of delinquent behavior and drug use than peers who spent less time with their parents.

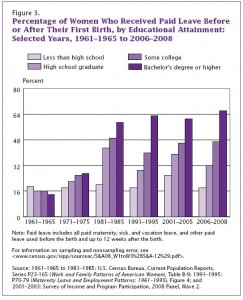

The authors dug deeper, finding that when a parent was overly-tired, stressed, cranky, or feeling guilty, spending time with their children could lead to more behavioral problems and lower math scores. Nomaguchi says, “Mothers’ stress, especially when mothers are stressed because of the juggling with work and trying to find time with kids, that may actually be affecting their kids poorly.” This particularly impacts parents from low-income households who often lack access to social resources for improving mental health, but still feel the pressure to be “good” parents by spending time with their children. In fact, Milkie and Nomaguchi found that the biggest indicators of child success were mothers’ income and education levels:

“If we’re really wanting to think about the bigger picture and ask, how would we support kids, our study suggests through social resources that help the parents in terms of supporting their mental health and socio-economic status. The sheer amount of time that we’ve been so focused on them doesn’t do much,” says Milkie.