Like a bomb explosion, the number of American deaths from opioid abuse has quadrupled in four years to 66,000. Globally, there are about 200,000 estimated opiate-related deaths, in most cases avoidable, according to the report released on June 22, 2017 by the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

The Addiction Explosion & Deaths of Despair

On a global level, heroin seizures remained stable. However, seizures spiked in 2015 in the United States, where opioid abuse is particularly acute. The country now accounts for nearly a third of all drug-related deaths worldwide. America has about 4 percent of the world’s population — but about 33 percent of the world’s drug overdose deaths.

How did this epidemic happen in the United States? The US has always been ahead of much of the world in opiate-related overdose deaths — for a variety of reasons. For one, Americans are relatively wealthy, so they can afford to buy drugs. But there also appear to be cultural and socioeconomic factors at play, driving a broad increase in “deaths of despair” — such as suicides, alcohol, and drug overdose deaths.

According to an article at the website Vox, “if you ask experts what these causes (of despair deaths) could be, you can expect them to name, well, basically everything — a weak social safety net in the US compared with other developed countries, poor access to health care in general, subpar mental health care and addiction services, manufacturing jobs moving out of the country, cuts to local government services like parks and recreation, individuals losing a sense of spiritual or existential meaning, and so on.”

Another major reason the epidemic started in the United States, is that pharmaceutical companies heavily marketed to American doctors, but more significantly, they saturated the media with opioid advertisements to consumers, which has not been possible in most other countries. Furthermore, Big Pharma marketed opioids for chronic pain, even though the evidence for their effectiveness with chronic pain is very slim, and their potential for causing harm very strong.

Prescribed pain killers like oxycodone and hydrocodone are not the only culprit. Deaths from an opiate cousin, heroin, have been even more prevalent until recently. In America, the rise of deaths from heroin and fentanyl has been much faster than from opiate overdoses.

Opiates are generally prescribed for pain, but mental depression is an even greater motivator than pain for both prescription opiates and heroin. Several researchers now believe depression, one of the most common medical diagnoses in the U.S., might be a major cause driving many patients to seek out prescription opioids and to use them improperly. Mark Sullivan (2012), a professor of psychiatry at the University of Washington, concluded that depression tends to exacerbate pain, making chronic pain last longer and hurting the recovery process after surgery. “Depressed people are in a state of alarm,” he said. “They’re fearful, or frozen in place. There’s a heightened sense of threat.” That increased threat sensitivity might also be what heightens sensations of pain (Khazan 2017).

Not only do people with depression tend to be more pain-sensitive, the effect of opioids can, for some, feel as mood-elevating as an antidepressant. “Depression is a mixed bag,” Sullivan said. “People can feel sluggish and uninterested, but they can also feel agitated, irritated, and anxious. They feel both unrelaxed and really unmotivated at the same time.” Sullivan and other researchers from Washington and California in 2012 found that depressed people were about twice as likely as the non-depressed to misuse their painkillers for non-pain symptoms, and depressed individuals were between two and three times more likely to ramp up their own doses of painkillers. Adolescents with depression were also more likely, in one study, to use prescription painkillers for non-medical reasons and to become addicted (Khazan 2017).

A different group of researchers found that depressed people were likely to keep using opioids, even when their pain had subsided and when they were more functional. “If the emotional pain, the depression, is never properly diagnosed or treated, the patient might continue taking the opioid because it’s treating something,” said Jenna Goesling (2015), an assistant professor in the department of anesthesiology at the University of Michigan.

These researchers found that mood disorders nearly doubled the risk that a person already using opioids would continue to use in the long-term. “People are treated like innocent victims when they present pain complaints,” Sullivan said. But depression, wrongly, “feels like more of a personal failing than being in pain.” After all, it’s easier to explain not being able to get out of bed because of a bad back than crushing sadness.

Depression is widely under diagnosed and untreated, and the shortage of mental-health providers is especially acute in rural areas where the opioid epidemic has hit hardest. Goesling (2015) pointed out that we could get closer to untangling the messy connection between pain and depression by improving access to mental health care for people who have chronic pain.

The Republicans’ new 2017 tax and health-care bill, however, doesn’t do that. Not only does it make major cuts to Medicaid, which in some states pays for half of all addiction treatment cases, it also will allow states to stop forcing insurers to cover mental-health treatment. If it is driven—at least in part—by depression, opioid abuse should be seen as a cry for help. “People have distress—their life is not working, they’re not sleeping, they’re not functioning,” Sullivan said, “and they want something to make all that better.”

A review of the relationship between depression and opioid misuse by Khazan (2017) concluded that mental depression appears to be the largest cause of both overuse and abuse of opioids. The conventional wisdom views opioid addiction and abuse as the fault of over prescription and weak will power. However, the evidence points to an epidemic of depression and perceived meaninglessness as the best explanation for the rise in opioid and heroin addiction. Tragically, at the same time as deaths from opioid and heroin addiction rise, new federal and state cuts are being made in budgets for mental health research and treatment.

Opiate Deaths Reflect Rise of Social Despair

As I discussed in a short article on the WorldSuffering.org website, Case and Deaton (2017) found that midlife mortality from ‘deaths of despair’ since the year 2000 had risen sharply in the United States among White non-Hispanics age 50-54. Meanwhile, during the same time period deaths of people age 50-54 declined in Germany and France. And in Sweden, the UK, Canada, and Australia the trends were flat or steady.

In my previous article, I argued that these stresses arise out of a loss in meaning by a culture caught in excessive, self-centered consumption. In 2015, researchers reported that life expectancy was falling in middle-aged, middle America. Professors Case and Deaton concluded that these deaths of despair were a function a sense of hopelessness bred from a long run stagnation in wages from those with little education, low income, and middle age.

White Americans for generations have found meaning in their lives by aiming to give their offspring (and their children’s children) a better, more comfortable life. No wonder those in this social demographic feel a sense of despair and meaninglessness from knowing their children and grandchildren will be even worse off than their parents and grandparents.

Our nation’s future well-being depends upon reducing the tremendous inequality of wealth in the United States. Huge disparities in income or wealth tend to diminish the meaningfulness of one life within such societies. No wonder that middle-class Americans die early from combinations of despair, anger, obesity and addictions.

Can the America Survive an Epidemic of Despair and Anger?

Over this past year, American society as revealed in the media appears to be locked in constant anger, meanness, unhappiness, and even despair. People at opposite political extremes refuse to work together and rarely do they engage in dialog. The main political narratives claim that the ‘other side’ is to blame for everything wrong with society. That belief leads them to get all of their news and “facts,” from a media silo consistent with their political viewpoints.

Not only does such a society perpetuate greater anger, fear and other negative emotions, but the future for their offspring looks bleak indeed. With the absence of civil society and caring neighbors, what incentives do we have to work together in common causes? Are there not fewer incentives to help our fellow human beings in dire straits? Are there not fewer reasons to remain sober and live a full and meaningful life? Those that take up lifestyles of excessive substance abuse, have little reason to live. Their increasingly meaningless lives make them much more susceptible to despair and suicide.

The World Health Organization (2017) estimated that in 2009, 23.5 million Americans aged 12 and above required addiction treatment. Worldwide their estimate is that 230 million suffered from addiction, and the total social cost of that addiction adds up to over a half Trillion dollars. In addition, deaths due to addiction spiked even higher after 2015.

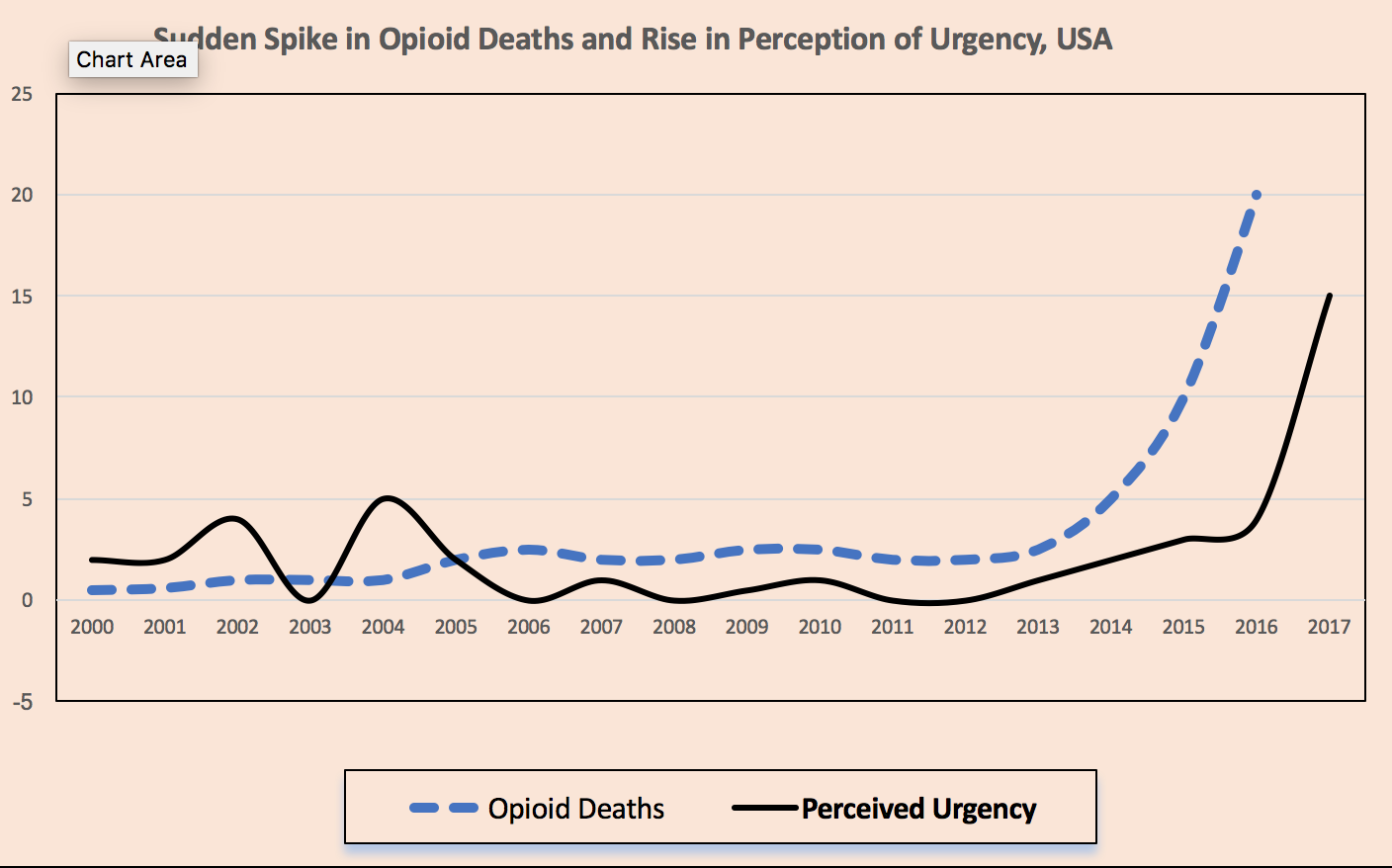

That America’s rise in deaths due to opioid/heroin overdosing is a very recent epidemic that has to be visualized to comprehend its suddenness and its tragedy. The figure below shows with the line of dashes the thousands of opioid deaths per year. For the past four years, the number of deaths has doubled each year. In 2016 there were 20,000 opioid deaths. This does not include heroin deaths, which until 2015 were even more prevalent than opioid deaths. In 2016 there were 16,000 heroin deaths.

The solid line represents the percent of the American public who said “drug/alcohol abuse is the most urgent health problem facing this country” as asked by the Gallup Poll in the United States. Not until 2014, was the substance abuse problem considered serious by the public. Within a year’s time it has become a man-made disaster. Unfortunately, the media and the politicians do not yet recognize that leading causes of this epidemic are depression and despair, not just over-prescription or lack of will-power.

Meaning and Purpose Therapy

Research on the meaning of life for different types of people has produced the non-intuitive finding that meaning is more important than happiness because a life filled with purpose and meaning yields a deeper happiness than possible from pleasure alone. Alcohol and drug addiction represents the epitome of pleasure-seeking, yet it yields the user only a sliver of pleasure and fleeting episodes of low-grade happiness. Research reveals that a major drag upon the well-being of heavy substance abusers is depression, which traps the user by making substance abuse easier, further magnifying depression, despair and anger. Can our social and political system survive a society dominated by anger and despair?

Can addiction and meaning co-exist? An addicted person can persist in a purpose such as helping others, but over time the most meaningful activities will be squeezed out by the demands of feeding an addiction. This is especially true of addictions to substances that cause physical dependency like alcohol and opiates. While addiction sometimes encompasses excessive eating, the dependency and side effects of addictive chemicals is far greater, so in this discussion, addiction refers to substance abuse including alcohol.

Addiction is both a product of depression and a producer of more depression. Addiction to alcohol, and other addictive substances results in even deeper depression and possibly anxiety and uncontrolled anger. The addict feels like being in a dark place, trapped in loneliness, guilt, anger and obsessively trying to get chemical ‘fixes.’ Such a state makes it very hard to think about meanings and purposes other than acquiring whatever makes them feel a “high.” Paradoxically, a lifestyle of feeding an addiction that makes one feel momentarily happy, very often ends in clinical depression.

Activities such as caregiving, which give one purpose and meaning, help ‘immunize’ us from addiction. Also, after treatment for addiction disorders, recovery tends to be more effective and long lasting if someone in treatment acquires a greater sense of purpose and meaning.

Social work professors Diaz, Horton and Malloy (2016) conducted a study of severely addicted persons in a treatment center and found that the lack of ultimate meaning in life, an important dimension of spirituality, is associated with alcohol abuse and drug addiction, as well as other mental health problems including anxiety and depression. Likewise, meaning of life intervention and training has been shown to assist making recovery more successful. The researchers discovered that the following meaning-oriented activities: creative arts, serving others, integrating selfhood through meditation or prayer during addiction treatment helped those recovering to recover more rapidly. Their conclusion was that treatment for addiction should include activities for training recovering addicts in how to develop greater purpose and perceived well-being.

Psychologist Paul Wong and his associates (2010) specialize in meaning therapy and have given a variety of suggestions for treating addiction with meaning. They state that

“Your life has intrinsic meaning & value because you have a unique purpose to fulfill. You are endowed with the capacity for freedom and responsibility to choose a life of meaning & significance. Don’t settle for anything less. No matter how confusing & bleak your situation, there is always beauty, truth, & meaning to be discovered; but you need to cultivate a mindful attitude and learn to transcend self-centeredness.”

They say an addict should “let compassion be your motive and may you see the world and yourself through the lens of meaning & virtue. You will experience transformation and authentic happiness when you practice meaningful living.”

Strategies for Recovery

The following strategies assist recovery from addiction, but they apply to anyone who wants to add more meaning into his or her life. First, whenever you have a choice to make during a day, choose on the side of increasing meaningfulness and strengthening purpose. This will produce the direct benefit of making your activities and relationships intrinsically more satisfying. In other words, authentic happiness will follow from authentically meaningful goals and actions.

Second, re-authoring your life by switching from your tendency to play the part of victim to playing the part of victor. For example, if you feel put-upon by your children needing your time, remember the privilege of having the children and how special they are.

Third, think of your life, not just in terms of interpersonal connections, but in terms of community and contributions to society. You may be surprised how much better you feel about yourself and your life by merely contemplating the way in which you link to the goodness of your larger community and society.

Beginning the road to greater well-being should start not only with a commitment to focus on meanings but to restructure our daily routines. Sometimes, the process of adding meaning simply involves reconstructing the way we think about the contribution we make to others as well as ourselves.

References

Case, A. & Deaton, A. (2017). Mortality and Morbidity in the 21st Century. Washington DC: Brookings Papers on Economic Activity.

Diaz, N., Horton, G., Malloy, T. (2016). “Attachment Style, Spirituality, and Depressive Symptoms Among Individuals in Substance Abuse Treatment,” Journal of Social Service Research 17 (April), Pp. 1-12.

Goesling, J., & 6 co-authors. (2015). Symptoms of Depression Are Associated With Opioid Use Regardless of Pain Severity and Physical Functioning Among Treatment-Seeking Patients With Chronic Pain. Journal of Pain. 16(9), Pp 844-51.

Khazan, O. (2017). How Untreated Depression Contributes to the Opioid Epidemic. The Atlantic (May 15). Accessed on 15 Nov. 2017 at https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2017/05/is-depression-contributing-to-the-opioid-epidemic/526560/

Sullivan, M. (2012). Depression and Prescription Opioid Misuse Among Chronic Opioid Therapy Recipients With No History of Substance Abuse. Annals of Family Medicine 10(4), pp. 304-311.

UNODC (UN Office on Drugs and Crime), (2017). World Drug Report, 2017. Accessed on 11 Dec. 2017 at https://www.unodc.org/wdr2017/

Vox (2017). America leads the world in drug overdose deaths by a lot. Accessed on 11 Dec. 2017 at https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2017/6/28/15881246/drug-overdose-deaths-world

World Health Organization. (2017). World Drug Report 2017. Retrieved on 14 Nov. 2017 from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.708.9802&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Wong, P. T. P., Nee, J. J. & Wong, L. C. J. (2010). A Meaning-Centered 12-Step Program for Addiction Recovery. Retrieved on 14 Nov. 2017 from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.708.9802&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Comments