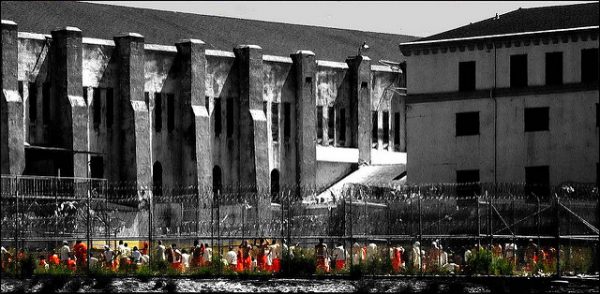

This past August, the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee, a labor union for prisoners, began a nationwide strike to protest against inhumane conditions, the use of solitary confinement, and precarious work in U.S prisons. Fighting prison conditions and labor precarity has been a long-standing struggle for prisoners in the United States and around the world, and social science research explains the dynamics underlying this struggle.

As ‘total institutions” prisons provide poor substitutes of basic needs, or limited access to basic items, services, and comforts like hygiene items, clean clothing, nutritious food, education, and health care services. Consequently, prisons end up depriving inmates of their wellbeing, autonomy, sense of self-worth, and control over their fates. In the United States, the indignities of prison conditions range from major maltreatments, such as the abuse of long-term solitary confinement, to minor cruelties, such as restricting the use of showers and toilet paper (imagine being limited to just one roll per month), in overcrowded facilities.

- Erving Goffman. 1961. Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates. Garden City, New York: Anchor Books.

- Keramet Reiter. 2016. 23/7: Pelican Bay Prison and the Rise of Long-Term Solitary Confinement. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Heather Ann Thompson. 2017. Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and its Legacy. New York: Pantheon.

The specific conditions of prison labor reflect long-standing contradictions. On the one hand, social science evidence suggests that providing jobs to inmates has a positive effect and can reduce their involvement in future crime activities. On the other hand, prison labor has also led to abuse and exploitation. Correctional facilities use prison labor to serve private industries, to perform cleaning and maintenance functions within facilities, or even to repair public water tanks and fight wildfires. Prison labor has also served as an instrument of economic policy in the labor market. In the 1990s, for example, rates of unemployment declined when a massive number of able-bodied working age men went to U.S. prisons.

- Christopher Uggen. 2000. “Work as a Turning Point in the Life Course of Criminals: A Duration Model of Age, Employment, and Recidivism.” American Sociological Review 65(4): 529-546.

- Phillip Goodman. 2012. “‘Another Second Chance’: Rethinking Rehabilitation through the Lens of California’s Prison Fire Camps.” Social Problems 59(4): 437-458.

- Bruce Western and Katherine Beckett. 1999. “How Unregulated is the US Labor Market? The Penal System as a Labor Market Institution.” American Journal of Sociology 104(4): 1030-60.

- Joshua Page and Joe Soss. In Progress. Preying on the Poor: Tough on Crime as Revenue Racket. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Imprisonment often has devastating consequences for inmates, their families, communities, and society at large. Even though certain policies like prison labor may involve potential benefits, their positive effects only occur when there is a genuine effort to achieve inmates’ social inclusion. Inmates’ struggles to achieve effective changes in their living conditions therefore require sustained and special attention from the public and policy makers.