The new Netflix show, Maid, based on the best-selling memoir by Stephanie Land, chronicles a mother’s journey out of domestic violence and towards safety. The story offers an intimate portrait of the many barriers facing impoverished mothers, including the never-ending obstacles in securing government assistance.

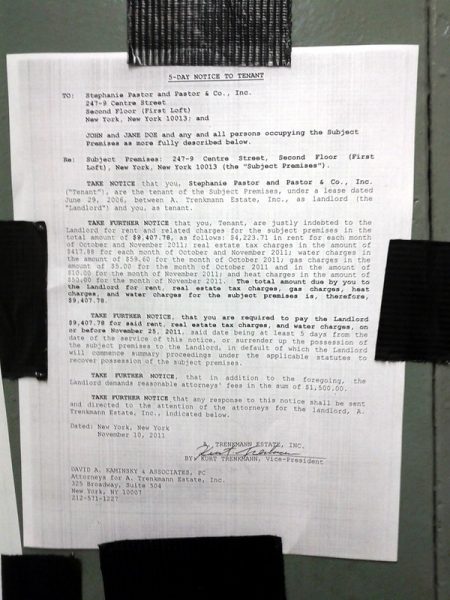

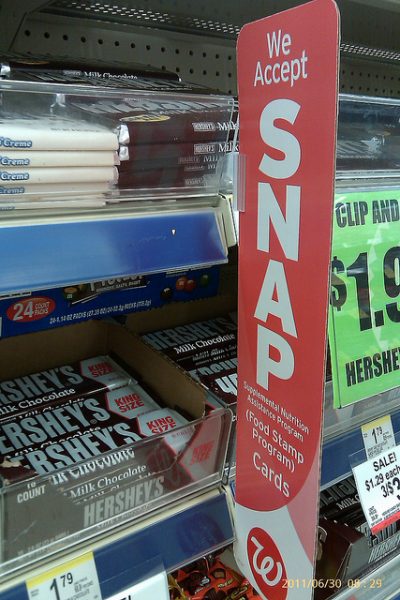

Sociological research has consistently found that the welfare system inadequately serves the poor. From red tape to contradictory policies, accessing government assistance is notoriously difficult to navigate. Further, welfare is highly stigmatized in the United States with shame and coercion baked into its process.

Due to gendered expectations of parenting, mothers face increased scrutiny about their children’s well being. In particular, mothers of low socioeconomic status are often harshly judged for their parenting without consideration of the structural inequities they face. Mothers seeking assistance from the welfare system are often judged because of cultural stereotypes about motherhood, poverty, and government assistance.

- Sarah Halpern-Meekin, Kathryn Edin, Laura Tach, and Jennifer Sykes. 2015. It’s Not like I’m Poor: How Working Families Make Ends Meet in a Post-Welfare World. Oakland, California: University of California Press.

- Brianna Turgeon. 2020. “When ‘Best I Can’ Is Not Enough: Welfare Managers’ Appraisal of Clients’ Mothering Practices.” Sociological Inquiry 90(4):839–66.

- Brianna Turgeon, and Kaitlyn Root. 2019. “Welfare Mothers in the United States.” in The Routledge Companion to Motherhood. Routledge.Melody K. Waring, and Daniel R. Meyer. 2020. “Welfare, Work, and Single Mothers: The Great Recession and Income Packaging Strategies.” Children and Youth Services Review 108:104585.

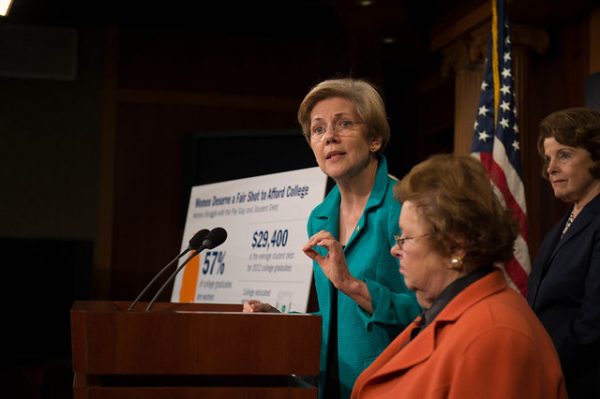

The U.S. welfare system has been a contentious subject for decades with public perceptions of poverty influencing the social safety net. The derogatory infamous image of the “welfare queen” – an allegedly lazy or irresponsible woman who exploits government programs – demonstrates how racist images of poverty and motherhood directly impacted policy making. This body of work takes a historical perspective on welfare and motherhood to consider how gender and racial stereotypes influence public policies.

- Ange-Marie Hancock. 2004. The Politics of Disgust: The Public Identity of the Welfare Queen. New York: NYU Press.

- Gwendolyn Mink. 2018. The Wages of Motherhood: Inequality in the Welfare State, 1917–1942. Cornell University Press.

- Ellen Reese. 2005. Backlash against Welfare Mothers: Past and Present. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Theda Skocpol. 1996. Protecting Soldiers and Mothers: The Political Origins of Social Policy in the United States. 1. Aufl., 4. Druck. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

- Joe Soss, Richard C. Fording, and Sanford F. Schram. 2011. Disciplining the Poor: Neoliberal Paternalism and the Persistent Power of Race. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

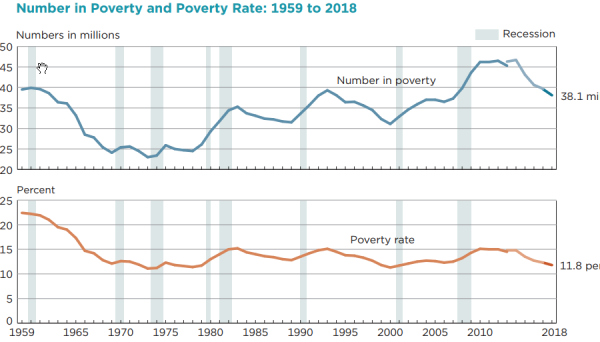

Much research directly contradicts the welfare queen trope, showing instead how impoverished families have fallen through the cracks of the welfare system. This work highlights the astounding income inequality in the contemporary United States and the resourcefulness and resiliency of impoverished families and individuals and their struggle to survive on little-to-no resources.

- Stefanie DeLuca, Susan Clampet-Lundquist, and Kathryn Edin. 2016. Coming of Age in the Other America. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Kathryn Edin and H. Luke Shaefer. 2016. $2.00 a Day Living on Almost Nothing in America.