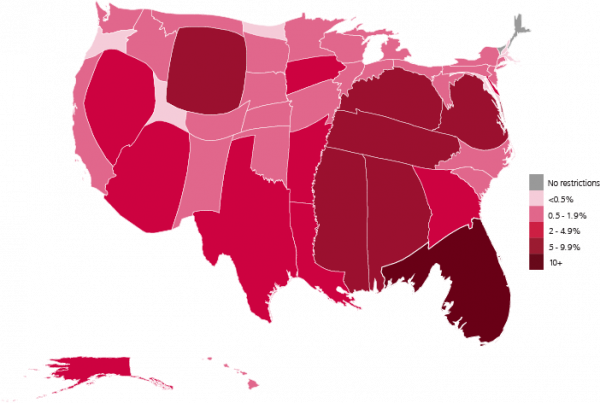

Donald Trump was recently the first sitting president to address the Values Voter Summit in Washington, D.C., where he referenced “attacks” on Judeo-Christian values. But what does this “Judeo-Christian” buzzword really mean? Social science research shows us that national identity is a style of political engagement that can change over time, but also that these cultural changes have real stakes for the way Americans think about their fellow citizens. While the U.S. is becoming an increasingly racially and religiously diverse nation, this demographic change comes up against the persistent cultural assumption that Americans share a distinct Christian identity and heritage.

The meaning of “Judeo-Christian” has changed over time. Once referring to progressive political coalitions, it became a rallying cry that designated socially conservative positions in the “culture wars” of the 1980s and beyond. This case shows us how nationalism is a cultural style comprised of different beliefs and identities. This means that political leaders and everyday citizens can draw on different styles of nationalism.

- Douglas Hartmann, Xuefeng Zhang, and William Wischstadt. 2005. “One (Multicultural) Nation Under God? Changing Uses and Meanings of the Term ‘Judeo-Christian’ in the American Media.” Journal of Media and Religion 4(4): 207–34.

- Bart Bonikowski and Paul DiMaggio. 2016. “Varieties of American Popular Nationalism.” American Sociological Review 81(5): 949–80.

- Rhys H. Williams. 2013. “Civil Religion and the Cultural Politics of National Identity in Obama’s America.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52(2): 239–257.

And these styles of nationalism have real stakes. An emerging trend in public opinion literature shows that Christian nationalism in particular is a strong predictor of negative attitudes toward minority groups. For example, respondents high on this kind of nationalism are also less likely to support interracial and same-sex marriage.

- Samuel L. Perry and Andrew L. Whitehead. 2015. “Christian Nationalism and White Racial Boundaries: Examining Whites’ Opposition to Interracial Marriage.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 38(10): 1671–89.

- Andrew L. Whitehead and Samuel L. Perry. 2015. “A More Perfect Union? Christian Nationalism and Support for Same-Sex Unions.” Sociological Perspectives 58(3): 422–40.