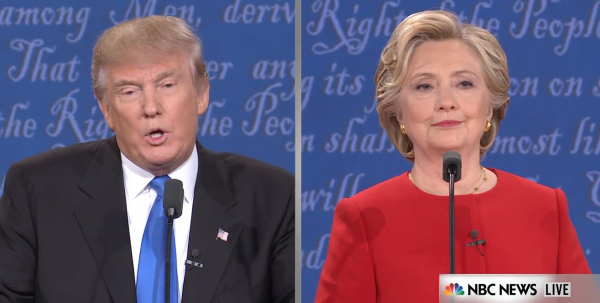

If you didn’t notice the rampant interruptions during this week’s first presidential debate between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, don’t worry – several sources ranging from Vox to The New York Times and even U.S. Weekly took note. While estimates vary as to the exact number of times each candidate interrupted the other, some estimate that Clinton interrupted Trump about a dozen times while Trump interrupted both Clinton and debate moderator Lester Holt over 50 times. As this is likely a moment we will teach in Sociology of Gender courses for years to come, we can look to prior studies of speech patterns and gender to contextualize the demeanor of the debate.

Both men and women engage in all types and styles of interruption; however, men are more likely to engage in intrusive interruption — that is, when someone interrupts “the speaker’s turn at talk with the intent of demonstrating dominance.” Additionally, men interrupt women more often than they do other men, using sex as a status characteristic in group discussion.

- Kristin J. Anderson and Campbell Leaper. 1998. “Meta-Analyses of Gender Effects on Controversial Interruption: Who, What, When, Where, and How.” Sex Roles 39(314): 225-252.

- Lynn Smith-Lovin and Charles Brody. 1989. “Interruptions in Group Discussions: The Effects of Gender and Group Composition.” American Sociological Review 54(3): 424-435.

Gender also plays a role in interruptions among deliberating bodies, particularly when women are the minority within the group. When outnumbered, women experience higher rates of dismissive interruption and lower rates of approval when speaking.

- Tali Mendelberg, Christopher F. Karpowitz, and J. Baxter Oliphant. 2014. “Gender Inequality in Deliberation: Unpacking the Black Box of Interaction.” Perspectives on Politics 12(1):18–44.

Interruption, regardless of gender, has social consequences. Someone who interrupts is often seen as more successful, though less socially acceptable and reliable.

- Mary Glenn Wiley and Dale E. Woolley. 1988. “Interruptions Among Equals: Power Plays that Fail.” Gender & Society 2(1): 90-102.