For the first time since 2006, the Census finds a .5 percentage drop in the poverty rate, with children and Hispanics seeing the biggest declines. Before taking these encouraging statistics at face value, it is important to put them into context. Briefs produced by the Stanford Center on Poverty and Equality and the Center for American Progress outline important factors that often get ignored when focusing on the poverty rate alone, including the consistent struggle for young adults and minorities to find work and the ever-increasing working poor that often get left out of the poverty conversation entirely.

The high poverty rate among young adults is cause for concern. Experiencing poverty in early adulthood has been found to hinder future earnings, especially within minority populations. Young people may stay hungry if our definition of poverty doesn’t grow up with them.

- Andre Mizell. 2000. “Racial and Gender Variations in the Process Shaping Earnings’ Potential: The Consequences of Poverty in Early Adulthood.” Sociology & Social Welfare 27(2).

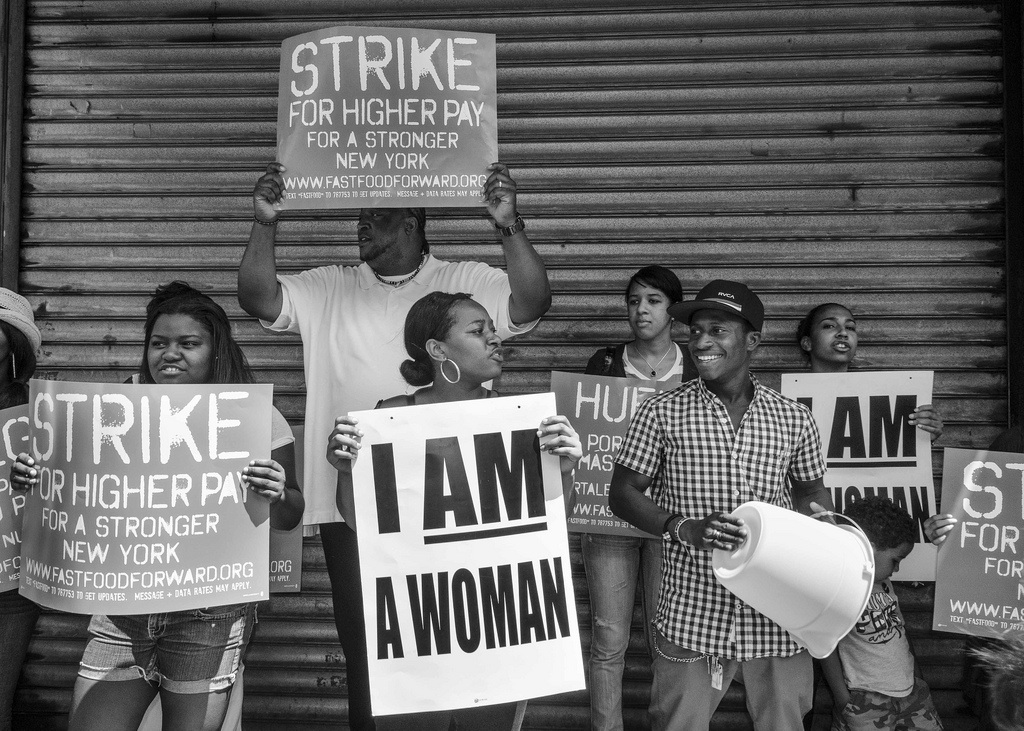

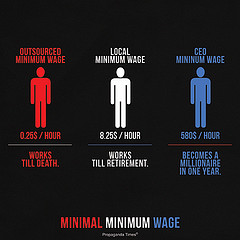

While the poverty rate may have dropped slightly, this is largely due to the increase in the working poor. Millions of families are trapped in the middle, earning just enough to be considered above the poverty line but making far from enough to be considered economically secure. Poverty among working adults is linked to a broader decline in labor unions.

- David Brady, Regina S. Baker, and Ryan Finnigan. 2013. “When Unionizations Disappears: State-Level Unionization and Working Poverty in the United States.” American Sociological Review 78(5).

Most of the discussion around the poverty rate centers on what David Cotter calls “person poverty” as opposed to “place poverty.” In his analysis of Census data, Cotter finds that, regardless of any individual characteristic, households in rural America are more likely to experience poverty than their metropolitan counterparts.

- David Cotter. 2002. “Poor People in Poor Places: Local Opportunity Structures and Household Poverty.” Rural Sociology 67(4).

Our partner Scholars Strategy Network has tons of great briefs on this issue, including this one on the need for a more comprehensive measure of poverty.