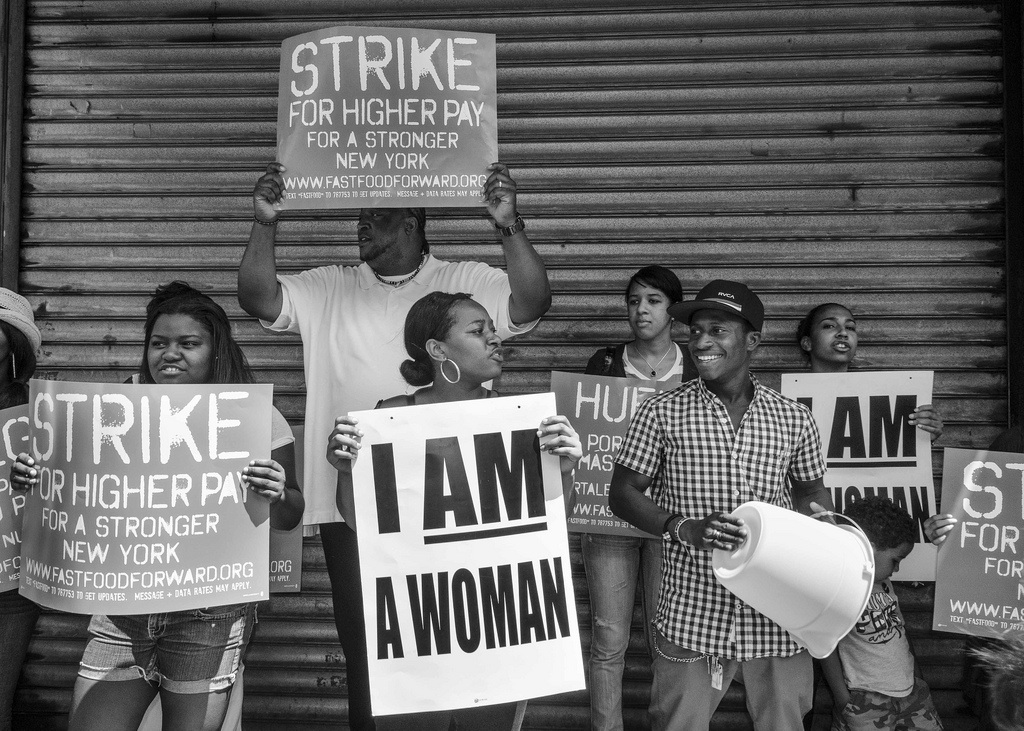

One of the most popular new movies in the past month was Hidden Figures, a film that highlights the forgotten story of three Black female NASA employees who were integral to the success of several U.S. space missions in the early 1960s. The film allows audiences to observe both the subtle and blatant instances of sexism and racism that plagued women in STEM, despite the prestige of the field. Over 50 years later, women’s employment in science, technology, engineering, and math remains low compared to that of their male peers, especially among minority women. Social science allows us to piece together where and how these gender differences develop, and how women within STEM careers successfully navigate their environments.

Despite growing numbers of women receiving college degrees, they remain underrepresented within STEM fields. While some research attempts to find biological explanations for gender and racial disparities, a myriad of social science scholars note that cultural stereotypes equate science and math studies with men’s work. As such, young women frequently experience lower self-confidence in their science and mathematical skills. Women of color, in particular, are less likely to attend elite schools with quality STEM programs and are more likely to experience family unemployment. These barriers limit access to the resources necessary to cultivate engagement with STEM studies.

- Yu Xie, Michael Fang, and Kimberlee Shauman. 2015. “STEM Education.” Annual Review of Sociology 41: 331-357.

High school environments account for much of the dearth of women in STEM careers. Research finds that 12th grade girls who attend high schools that fail to foster support for girls in science and mathematics, and that encourage gender segregation within extracurricular activities, are less likely to list a STEM career as a potential field of study.

- Joscha Legewie and Thomas A. DiPrete. 2014. “The High School Environment and the Gender Gap in Science and Engineering.” Sociology of Education 87(4): 259-280.

When women enter STEM work spaces, they often experience microaggressions from their male peers, despite receiving the same degrees and having the same skills. Interviews with women working in technology firms revealed that those who identified as heterosexual and traditionally feminine recalled having a harder time in their workplaces because male peers avoided eye contact, questioned their work more than other male peers, and critiqued their clothing choices. Gender-fluid and LGBTQ women, on the other hand, reported an easier time navigating their predominantly male workplace because their styles conformed to the masculine subculture of the workplace.

- Lauren Alfrey and France Winddance Twine. 2016. “Gender-Fluid Geek Girls: Negotiating Inequality Regimes in the Tech Industry.” Gender & Society 31(1): 28-50.