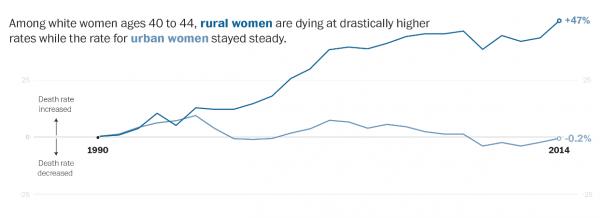

The Washington Post highlights the growing morbidity and mortality rates of rural white women. The rates of sickness and death for white women have climbed steadily over the past couple of decades, but the most dramatic increase is in rural areas. Sociologists and demographers have long investigated these trends. Poverty, stress, and timing of childbirth all matter for mortality, but the combination of these factors have stronger effects on rural, white women—surprising, because poverty confounds our typical understandings of race and inequality.

Mortality rates have decreased overall since the latter half of the 20th century, though several factors, many related to poverty and education, contribute to the increasing death rates of certain groups. Those with less education tend to have higher mortality rates and rates of heart disease and lung cancer.

- Ryan K. Masters, Robert A. Hummer, and Daniel A. Powers. 2012. “Educational Differences in U.S. Adult Mortality: A Cohort Perspective,” American Sociological Review 77(4):548–72.

Less education tends to correlate with lower socioeconomic status and difficulty finding employment. Sociologists Link and Phelan point to poverty as a “fundamental cause” of mortality and morbidity. Low socioeconomic status means difficulty is accessing resources: not only do poor people have trouble obtaining the means to maintain a healthy life, they also tend to lack the time, transportation, social networks, and money to help them recover from sickness.

- Bruce G. Link and Jo Phelan. 1995. “Social Conditions as Fundamental Causes of Disease,” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 80–94.

Some of the health issues tied to poverty affect women more than men. Women with high stress levels are more likely than men to die from cancer-related illnesses. Other health patterns related to social class, such as the timing of childbirth, matter, too. Poorer women are more likely to have children before age 20, which correlates with increased risk of death, heart and lung disease, and cancer.

- Jennifer Karas Montez and Anna Zajacova. 2013. “Explaining the Widening Education Gap in Mortality Among U.S. White Women,” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 54(2):166–82.

- Kenneth F. Ferraro and Tariqah A. Nuriddin. 2006. “Psychological Distress and Mortality: Are Women More Vulnerable?” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 47(3):227–41.

- John C. Henretta. 2007. “Early Childbearing, Marital Status, and Women’s Health and Mortality After Age 50,” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 48(3):254–66.

Comments 1

Giovanni Guzman — February 1, 2019

Women in rural areas of the ages 40-44 have seen an increase in mortality rate as opposed to women in urban areas whose mortality rate has remained steady. Such results are caused by the low socioeconomic status of those living in rural areas that doesn't allow them have the proper reinforces to live a stress and illness free life. These women have also been found to have kids before the age of 20, as a result they face many stressors that have caused them to obtain many diseases as a result,