Originally published in January 2016.

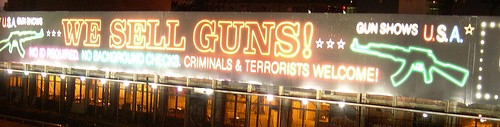

Americans are engaged in a great gun war, one that has raged for at least four decades. The war has intensified to the point where citizens cannot agree on the most basic facts. How many guns do Americans own? Does carrying firearms do more harm than good? Do firearm regulations work?

Although the answers are hotly disputed, most Americans share the goal of reducing our unconscionably high rate of gun violence. In a politically challenging environment, it makes sense to pull together what is known about guns and gun violence and look for policy approaches that could garner broad support. more...

Research to Improve Policy: The Scholars Strategy Network seeks to improve public policy and strengthen democracy by organizing scholars working in America's colleges and universities. SSN's founding director is Theda Skocpol, Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology at Harvard University.

Research to Improve Policy: The Scholars Strategy Network seeks to improve public policy and strengthen democracy by organizing scholars working in America's colleges and universities. SSN's founding director is Theda Skocpol, Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology at Harvard University.