Masculinity As Homophobia

Kimmel (2000) wrote what I consider one of the best articles on masculinity, sexism, and homophobia in his article Masculinity as Homophobia: Fear, Shame, and Silence in the Construction of Gender Identity. I am disappointed by the discussion of gender issues or gender stratification in textbooks. Reading through these chapters sexism, feminism, and homophobia are seen as women’s or gay and lesbian issues. Somehow the largest perpetrator of violence, aggression, and fear toward women and the LGTBQ community is somehow missing or only discussed indirectly. Many feminist researchers have rightfully criticized news headlines of rape incidents that say, “woman alleges rape” in the passive voice as opposed to, “man arrested for rape”. Textbooks that omit men and masculinity from discussions of sexism, feminism, and homophobia commit the same sin. In an effort to correct this omission I always incorporate discussions and critiques of masculinity in my courses.

Teaching students about masculinity issues is hard specifically because talking about masculinity is an unmasculine thing to do.

Traditional masculinity, according to Kimmel, is homophobic in the sense that any sign of femininity in a man is sure to draw emasculating criticism from his peers. Men, who subscribe to this narrow form of masculinity, then are afraid of or have a hatred of any none conforming men. Men and women emasculate non-conforming with words, violence, and isolation.

As a ice breaker into the subject, I ask the students to tell me what a “manly man” looks like, sounds like, walks like. Students can’t help but break into laughter as I take on all of the characteristics of a “manly man”. After that we talk about how gender is socially constructed and fluid. A great point of reference for this is the Maury Povich show. Maury frequently has a beauty pageant where some of the contestants are men in drag and others are women. He asks the audience to guess their gender. Most of my students have seen this show, so it is a great jumping off point to talk about gender as a social performance (Watch here at your own risk). I ask, “If gender is fixed and biological how could someone fool another into thinking they were a gender they are really not?” Students almost always jump on board the social construction bandwagon after this.

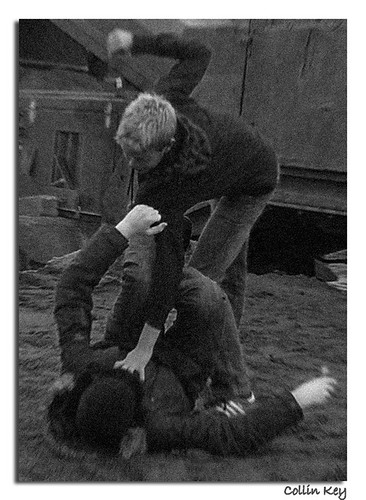

I also like to show a clip from the video Tough Guise that deals with many of the issues discussed in Kimmel’s article.

The Consequences of Narrowly Defined Masculinty

After we have clearly discussed how gender is socially constructed and defined what masculinity as homophobia means I ask my students to brainstorm the consequences men and women experience because of this narrowly defined masculinity. My students are quick to point out that many men do “stupid” risk taking behaviors to show they are tough. Students draw the obvious connection to the shamefully high levels of male violence toward women. Many men, they typically say, are hostile or even violent to gays and lesbians because a narrowly defined masculinity sees any non-compliance as an affront to their own masculinity. After this students usually go quiet.

I suggest that many father/son relationships are damaged by narrow definitions of masculinity. I ask my male students how many of their fathers are comfortable with hearing “I love you dad” from them? Many students laugh, suggesting that this is beyond the bounds of their relationship with their father.

At this point in the class I tell my students of a friend of mine, Ryan, who a few years back told me that he was going to buy a ring and propose to his girlfriend of many years. After a few weeks I had not heard any news of their engagement so I asked Ryan, “So did she say yes?” “No. We broke up a few days before I was going to propose,” Ryan said looking at the floor. “I’m sorry dude. That sucks. Did she tell you why she left?” Ryan put his tongue in the side of his mouth as though he was chewing on it and looked to the ceiling. After a long pause he said, “She said I was… emotionally unavailable.” He and I made eye contact again and he saw my perplexed look. After a few beats I said, “What the hell does that mean?” Ryan shrugged with and exclaimed, “I know, right?”

I tell my students it wasn’t until I started dating my wife that I finally understood what Ryan and his girlfriend were experiencing. A few weeks into our relationship my wife said something small that upset me. Seeing that I was upset she said, “Oh, how thoughtless of me. I have clearly hurt your feelings.” I scrunched my brow and responded, “Whoa lets not blow it out of proportion. I mean, that pissed me off, but it would take a whole lot more to hurt my feelings.” She showed me patience by letting it go for the moment, but a few weeks later something else upset me and she said again, “I hurt your feelings”. This happened many times over and each time I smiled or laughed it off and told her she was crazy. It wasn’t until a few months into the relationship that I finally woke up and said with a tone of surprise and discovery, “You know what… Just before I got pissed off I felt something… you DID hurt my feelings!”

Based on the looks my students give me I can tell that they think this story is contrived. How could the person who is teaching on the subject of masculinity be so oblivious to how it was affecting himself? I tell my students that I grew up in a family of four, my mom, dad, brother, and me. Being a 3/4 male household, I joke that our house was a, “toilet seat up house, if you know what I mean.” I share with them that I lived with men throughout my childhood and then with other men as roommates until the day I moved in with my wife. I was totally surrounded by men who, even though they loved me, didn’t discuss their or my emotions very often and when we did it was indirectly. After years of neglecting my emotions I had learned to not even acknowledge them. And in doing so I had lost part of my humanity.

Ryan and I were both emotionally unavailable. Both of us had lost touch with part of ourselves and this made us less able to be a equal partner with our loved ones. Fortunately for me I had a loving patient wife who gave me the space to find my way out of my narrowly defined masculinity box.

After this story I challenge my students to think of ways that women also emasculate men. Without fail a female student will say something like, “I have always thought that I didn’t want a boyfriend or husband who cried. I have even said aloud that to my friends.” Many men feel pressured to keep up their tough fronts around men and women. Women who stigmatize or ostracize men who are in touch with their emotions discourage multiple forms of masculinity. On the flip side women who flock toward men who put on the “bad boy” posturing reward the narrowly defined masculinity.

Kimmel argues that men feel powerless to masculinity. That even if they wanted to change their is little that a single person can do. This illustrates to students how social systems affect individuals, including themselves. The systemic nature of gender construction makes it perfect for any sociology course including a 101 course.

Every time that I have taught this subject in my class there have been male students who sit way back in their chairs, arms folded, with a disapproving look on their face. Early in my career I would say to myself, “Well not everyone is ready to get it.” But now I have come to realize that in all likelihood these are the very students who were most affected by what I and Kimmel had to say. That they were protecting themselves with the only tools our narrow definition of masculinity affords them. I often say at the end of my class “If you are put off by todays discussion or if you walk out of this room and say to your classmates, ‘What the hell was that guy talking about. He’s full of it.’ Then in all likelihood you are suffering from this narrowly defined masculinity the most.”

I feel I am at a distinct advantage teaching this class because I am a man. When I am critical of narrowly defined masculinity my students do not assume that I have an ulterior motive or that I am in some way a “man hater”. I can also role model a form of masculinity outside the narrow definition while still maintaining the power and authority given to me as a teacher. That said, I also feel a responsibility to teach this subject. This is a problem that affects me and that I have in thoughtless, low moments perpetuated the narrow definitions. I can discuss with my students how the narrow definition of masculinity has hurt me and how I have hurt others who didn’t conform. To be clear, I always am critical of my previous failings and repent for them in front of my class.

Comments