The video above is a fantastic illustration of how carefully manicured reality is. While filmmaker Adam Lisagor breaches social norms by dancing in an airport, the people around him do work to protect his failed performance and pretend that they don’t see him acting a fool. There are loads of public breaching videos, but at 64 seconds short, this video is begging to be included in your classes.

Videos for Class

Maybe it’s the Just World Hypothesis or maybe it’s the dichotomization of racism, but for whatever reason, students are quick to claim they’ve been cured of racism.[1] Racism, it would appear, is a big problem… for other people. Or older generations. Or other parts of the country (like in the South). According to many students, racism is a problem, to be sure, but it’s not a problem for them.

I’ve talked at length here at SociologySource about the need to teach our students that racism is more than overt hateful acts committed by ultra bigots. Racism (and all prejudice and discrimination for that matter) need to be conceptualized as problems “good, moral, and honest” people have. Furthermore, when we conceptualize all prejudice and discrimination as being big events carried out by mean people, we marginalize the day-to-day experiences of socially non-dominant peoples.

The concept of microaggressions helps my students understand the more everyday side of racism. Microaggressions are defined by Solórzano et al. (2002) as, “subtle verbal and non-verbal insults directed at non-whites, often done automatically or unconsciously” (Pp. 17)[2]. This conceptual framework also does a great job of separating the intent of an action from the impact that action has.

Franchesca Ramsey’s Sh*t White Girls Say About Black Girls is one of the best illustrations of the microaggressions concept[3]. Ramsey satirizes white microaggressions in a way that is both painfully funny and painfully honest.[4]

When this video came out it quickly went viral and then was parodied by a number of white actors who thought it was racist to point the finger at white women. The article “Not Everyone’s Laughing At ‘Sh*t White Girls Say To Black Girls’” by Tami Winfrey Harris at Clutch magazine does a fantastic job of reporting the backlash and critiquing the false equivalence of microaggressions targeted toward whites. Winfrey Harris uses microaggressions to analyze both Ramsey’s video and the backlash to it in her article and draws attention to the blog Microaggressions.com. This is a fantastic site of user submitted stories of microaggressions they have experienced in their everyday lives.

Pairing Ramsey’s video, Winfrey Harris’s article, and Microaggressions.com seemed like too potent a pedagogical opportunity to not use in my classes. I put together a quick written assignment for students to do before coming to class that will hopefully start a vibrant discussion on racism and microaggressions (Download it Word | pdf). Unlike most of the things I post here at SociologySource, I haven’t tried this one yet, but I plan to this fall.

If you’ve taught microaggressions before or if you have any suggestions/additions to this project hit me up on Twitter @SociologySource, on our Facebook page, or email me at Nathan @ SociologySource . Com.

-

To be clear, I do mean all students. While white students have been, in my experience, more likely to celebrate the end of racism, I have found that students of all racial ethnic groups espouse that same idea. Some students only argue that they are cured of racism and others argue that racism is no longer a real social problem. ↩

-

Solórzano, Daniel G. and Delgado Bernal, Dolores 2001 ‘Examining

transformational resistance through a Critical Race and LatCrit Theory Framework: Chicana and Chicano students in an urban context’, Urban Education, vol. 36, no. 3. pp. 308–42 ↩

-

The video is fantastic, but it’s not for everyone’s teaching style. I would also be more inclined to show it to an upper level or graduate level class. If you are going to show it to an intro to sociology class, I would highly recommend a large amount of time for class discussion and decompression. ↩

-

Do keep in mind that I am neither Black nor a woman, but I have heard something similar to most of the statements Ramsey makes. The video rings true to me. Just saying. ↩

When I was a kid my school had “multi-cultural” day- usually in February. It was our annual conversation about MLK and the Civil Rights movement. I remember asking my 5th grade teacher something to the effect of, “if today is ‘multi-cultural’ day, what are all the rest of the days?” I’ve been an “annoying sociologist” my entire life.

On these “multi-cultural days” we were taught one thing more than anything else, “don’t be racist”. Racism, I was told, was a problem had by ignorant meanies. Racism was an end state. It was something you were; like a title. This, as I’ve discussed before, is the dichotomization of racism.

A week or so ago, friend of the site Paula Teander or @sober_sociology sent me this TED talk by Jay Smooth about the dichotomization of racism (he doesn’t use those words). I like this video so much that I will certainly be using it in my 101 classes from now on.

He mentions in his talk another of his videos “How to Tell People They Sound Racist”:

What They Don’t Teach On Multi-Cultural Days

These are great and I totally plan on using them, but as a sociologist, I always want my students to know that while individual racism is terrible, institutional racism has a much bigger impact on the daily lives of people in our society.

That’s what they don’t teach you during “multi-cultural days”. When racism is discussed as an individual problem (whether it be an end state or a single act as Mr. Smooth suggests), it overlooks how racism can exist without any one person being actively and overtly racist. After we talk about racial institutional discrimination in housing, employment, banking, education, etc. I ask my students, “If I could wave a magic wand and make everyone never think, act, or speak in a racist manner ever again, would racial inequality evaporate?” The answer comes easily to my class.

The best lessons are the ones your students teach themselves. You can’t tell students anything, but you can give them the eyes to see their own behavior from a new light and they will teach themselves more than you could’ve ever dreamed.

I love gender because it’s written all over our bodies. Students come into class doing gender. You only need to draw their attention to their own gendered presentations and ask them to “see the familiar as strange”. That’s easier said than done.

When students see a “failed performance”[1] of gender the intentionality of their own “successful” gender performance comes into stark contrast.

Photographer Rion Sabean did a collection of “Men-Ups” where men were shown in poses that are stereotypically reserved for women in Pin-Up calendars. The photos are men, doing “manly” things, but they are posed in gender opposite ways.

Support Rion by purchasing a Men-Up calendar!

After my student’s have been shook awake and their own gender performance is drawn into the light, I ask them to help me come up with a list of “gender rules”. I split the room and half address how a person becomes a “girly girl” and the other addresses how a person performs as a “manly man”[2]

Below are some slides I put together to highlight gender performances and media presentation of the masculine and the feminine.

The Codes of Gender

The Media Education Foundation has a great film that addresses gender and imagery better than any other I’ve seen. I’ve always liked Sut Jhally’s work, but this one is his best since Advertising and the End of the World.[3] Pairing this video with the Men-Ups calendar images is a powerful one two punch.

I top all of this gender imagery with an assignment that ask my students to go find a photograph of men and women in stereotypic poses and critically analyze the image. You can find those directions here. Enjoy.

Footnotes:

-

This is not a moral judgment, but a reflection of many students own perceptions. I do not contend that there is a right, appropriate, or “normal” gender performance, but rather I contend that many students perceive there to be one. All gender expressions are equally valid and equally deserving of respect. Do your gender how you see fit. ↩

-

I tell my students to notice how we do gender with terms like “girly girl” and “manly man”. To be masculine is to be mature, but to feminine is to be infantalized according to the dominant stereotype. My students laugh when I ask them to consider if I asked them to tell me how to become a “womanly woman” or a “boyish boy”. ↩

-

Dr. Jhally if you are listening. Please please update this film. I’d love to show it in my classes, but the ads are comically out of date now. ↩

“I thought this class was going to be about the environment, but we keep talking about illegal immigrant workers.” is a statement one of my students years ago made in my environmental sociology class. The social inequality we see in a society is reflected in and reproduced by the the maltreatment of the environment. This is the foundational idea I want my students in environmental sociology to learn. However, drawing the connection between the two can at times seem counter intuitive to students.

I love the film Food, Inc. because it addresses how intertwined our social realities are to our environmental realities. The video pairs the exploitation of low level workers in the food industry with the tragic conditions animals are raised and slaughtered in. At one point in the film someone says that corporate food producers treat workers exactly like the treat their animals. Both will be gone soon, so it just easier to design the system to acquire them quickly, use them up, and discard them.

We see in the film how large food corporations use their power to shape the government regulations that are supposed to oversee their industry and protect consumers. Students learn that in some states legislation has been proposed that would make it a felony to snap a photo of a industrial food operation and how in all states its a crime to speak out against food producers under the “veggie-libel laws”. This film is perfect for any class that discusses Mills’s The Power Elite or anything from Marx.

While the film paints a grave picture of our current food situation in America, it’s not doom & gloom. Throughout the film I found myself thinking, “why are we producing food like this? This makes no sense.” I’ve yet to have a class where students were perplexed by the rampant irrationality of rationality on display in the entire industrial food production system. The film closes with actions that people can take and tells the viewer, “You have a vote on this system three times each day”. More than any issue I present in my environmental sociology class my students really seem motivated and confident they can affect a change. In particular students agreed with the CEO of Stonyfield Farm Organics who says in the film, consumers have far more sway on what grocers sell than they may perceive.

I created a viewing guide for my students to fill out as they watch the film (download it here) and a short writing assignment that focuses on the connection between the social and natural worlds (grab it here). Food, Inc is available on Netflix streaming for free and should mandatory viewing for all sociologists.

The photo above is on the projector screen when I turn and start class by asking, “What is this a sign for? That is, where would we see this sign and why would it be put up in the first place.” After some bewildered looks students state the obvious, “those signs are along the border.” “The border of Georgia1“I quickly ask. Students laugh softly, “No the Mexican border”. “Why?” I prod them. “Because that’s where all the illegals come from.” “Oh, I see,” I turn and point to the screen in the front of the room and continue, “Who can tell me what ‘social problem’ if any this sign could be associated with. That is, what name would we give to the social problem this sign reflects.” A chorus of voices says, “Illegal Immigration”.

I nod and say, “What if I told you that this social problem you call ‘Illegal Immigration’ is part of a grand story that powerful people in society have been trying to get you to believe? What would you say?” After a healthy pause I follow, “Could anyone in the class tell me the story of ‘Illegal Immigration’?” The silence in the room becomes deafening as my students turn and look around the room with perplexed looks on their faces. “Well then I’d like you to do some research and come back to me next week and tell me if you’ve figured out the story.”

The Research on “Illegal Immigration”

“Illegal Immigration” or undocumented immigration, as I’ll be referring to it, is a hot button issue that has been consistently in the news media for as long as I can remember. However the issue seemed to hit another peak in public attention when Arizona passed a highly punitive state law to enforce federal immigration policy. This was only furthered by the passing of copycat laws in Alabama and Georgia (just to name a few). Given all the media attention there is a lot of great resources out there for teaching the controversies around this social problem.

My students love it when I can pair academic sources with popular media. They really love it when we use multiple mediums. I’ve created an “immigration media collection” that includes the following. The collection is designed to present conflicting arguments from the opponents of and supporters of undocumented immigrants.

- “My Life as an Undocumented Immigrant” by Jose Antonio Vargas (Story featured in The New York Times Magazine).

- An audio podcast of a NPR Fresh Air Interview with Vargas & Mark Krikorian of the Center for Immigration Studies. Vargas goes into further detail in his half of the podcast and Krikorian talks about why he feels Vargas should be deported.

- A CBS Evening News report on how Georgia farmers are struggling to farm without undocumented immigrants.

- An episode of 30 Days where a Minute Man lives with an undocumented family. See below:

30 Days: Immigration from MacQuarrie-Byrne Films on Vimeo.

I pair all of these popular media with the chapter on immigration from our course textbook and it creates a powerful pedagogical tool. Students seemed to be really thinking about the issues deeply. Many students said it was only after they watched the video and read Vargas’s story that they wanted to know more about the facts and sociological research surrounding undocumented immigration. So, at least in this case, popular media created a hunger for scholarly research.

The Stories We Tell About Undocumented Immigration

After spending a week on undocumented immigration my students were primed to break down the narrative behind the social problem. When I asked, “What is the story or stories well tell about ‘illegal immigration’ in the United States?” My students quickly pointed to the border and that image I’d used to start our entire discussion. “The border isn’t the only problem.” I asked them to tell me more. “Around half of immigrants over stay their visas, so we could build a wall to the heavens and it wouldn’t end the problem of undocumented immigration.” I was impressed.

“What else,” I asked. There was a long pause before someone said, “The story we tell is only half the story.” With a prompt from me the student continued, “We only talk about the undocumented immigrants and we rarely if ever talk about the corporations that employ them.” “Bingo,” I replied. For the rest of the class we talked about conflict theory’s argument that powerful social actors use their influence to define social problems as being the responsibility or fault of the least powerful in society. “It’s all in the name,” one of my students said. “‘illegal immigration’ says it all. The problem is the ‘illegals’ not the employers who bring them here.” “Right,” I began, “we call it ‘illegal immigration’ and not ‘non-citizen exploitation’. Both names are apt, but as a society we’ve been convinced to focus on the former.”

While my students were feeling particularly anti-corporation I asked them if they play a role in undocumented immigration. Multiple heads shook left to right and someone mustered a, “No.” “What sectors of our economy do undocumented immigrants work in? That is, what jobs do they tend to have?” Quickly a list forms, “Farming, meat packing, factory work, landscaping, and housework,” were shouted out. Then I asked, “If undocumented laborers are paid an unfair wage for harvesting food or manufacturing products, does this not make them cheaper?” The obvious answer came easily. “Do you think that any of you have purchased any of these products made cheaper by undocumented immigration?” No one said a word, but heads slowly nodded. “So in that case all of you have directly benefited from undocumented immigration. You’ve had more money in your pocket because someone didn’t get paid what they should have, right?” The answer didn’t come as easy this time.

What I want my students to learn is that the story we tell about undocumented immigration is a simple one that blames only one group; the group with the least social power. In reality undocumented immigration is terribly complex and each of us in the United States has been either a victim or benefactor of harsh state and federal immigration policies. Once students accept that the world is far more complex than we are told it is on the news we can start to develop their sociological imagination.

Environmental sociology is great because it focuses on the biggest social system we have, the natural environment. The natural environment is at the center of culture, the economy, and every other social institution in one form or another. To understand environmental sociology is to understand social systems. The Story of Stuff is the best video I’ve found for explaining how individual actions, social systems, and the natural environment all intertwine. The video is just 21 minutes and available online making it an excellent resource to use in class or as a homework assignment.

If you teach Marx you need to show this video to your students. I’ve spent multiple classes trying to explain how capitalism (a linear system) and the natural environment (a finite resource) can not coexist long term, but it wasn’t until my students watched this video that they truly understood what Marx was trying to say. Furthermore, students seem to grasp how capitalism generated inequality and social injustice both in the U.S. and globally.

I’ve also used this video to teach my students about the difference between what we value and what we spend our money on. I’ll start class by asking students to write down a single item they possess that could never be replaced if it was lost. The item has to be something they would be heartbroken if they lost it forever. In the past students have written things like family photos, something a loved one passed on to them, or something mundane that holds a great deal of sentimental value to them because of who they were with when they first got it. After we watch The Story of Stuff I ask the students to flip the paper over and write down what items they spend most of their discretionary money on. Students write down things like clothes, video games, and smart phones. Then we start a class discussion about why the sentimental things we value are not the things we spend most of our money on.

This video is the gift that keeps on giving. Even if you don’t teach environmental sociology, this video would be a great inclusion for an Intro to Sociology class, a Social Problems class, and any class dealing with global issues or inequality.

The fundamental attribution error is so central to learning sociology that it astonishes me that I’ve never seen it covered in a Soc 101 text*. The fundamental attribution error is the idea that each of us as an individual is biased toward viewing our behaviors within the context of our circumstances. However, when we view the behaviors of others we attribute their behaviors to who they are as a person or to their character. The classic example is speeding.

To begin a class discussion on the fundamental attribution error I ask my students to think about the last time they broke the speed limit. Not like 5 miles an hour over, but like really really broke the speed limit. After a moment I ask, “So why were you speeding?” Students describe how they typically don’t recklessly speed unless there is some dire need to get somewhere fast. Students talk about being fired if they are late to work one more time, sleeping through an alarm and being late to a final or midterm, or speeding to catch a flight. Many times students start their explanations by saying, “I typically don’t speed, but…” When asked why they speed students provide a litany of circumstantial reasons for their “unusual” behavior.

I then ask students to think about the last time they were driving and someone blew by them or was weaving through traffic recklessly. After they collect this memory, I ask them how they feel about the speeding driver. “I typically yell, ‘you ___ hole!'” one of my students said this semester. Students go on to describe how they feel the reckless driver is a danger to society and they need to be stopped. Student describe speeders as fundamentally different people from them. They have a character flaw that makes them speed. There is almost always no discussion of how the other speeders may be experiencing circumstances similar to the times that students recalled speeding. Basically what pans out every time I have this discussion is that, students speed because of unique circumstances, but others speed because of who they are.

We can see the fundamental attribution error all over the place in sociology. It’s present in almost every stereotype. We see it in the criminal justice system. But where I experience the fundamental attribution error the most is in discussions of inequality. Students can go on and on about how they’re loved ones work extremely hard and still can’t get themselves out of poverty, but they also go on and on about how they know so many poor people who, unlike their loved ones, are lazy and unwilling to even try to live independent of government aid. I frequently hear a statement like this, “It makes me so mad to see all these people who live off of welfare whining about being broke when they aren’t even looking for work or trying to be independent. When my family was on welfare we used it because we had to and as soon as we could get off of it we did.” Statements like this show how students place their families use of welfare within the context of their circumstances, but they refuse to extend the same to other families on welfare. The character of these other families are fundamentally different from theirs. When we talk about empirical research that shows that the majority of welfare recipients only receive aid for a short period of time and then leave the programs as soon as they can, students seem perplexed. They tell me stories of people they saw picking up welfare checks in Cadelac Escalades. They tell me that despite my empirical evidence to the contrary, most people “abuse welfare” and their family was one of the rare exceptions. Knowing that this discussion is almost certainly coming, I start the semester with a discussion of the fundamental attribution error and I’ve found that students are increasingly willing to accept the empirical evidence.

Discussions of authority and obedience are another area ripe for the fundamental attribution error. In my class we watch a clip about the Stanford Prison experiment, read about Millgram’s electrocution experiments, and the like. Students learn about all these examples of obedience with disbelief. Students almost always say something like, “Well all this research shows is there are some gullible and obedient people out there.” Here again is the fundamental attribution error. My students believe that these “obedient people” are fundamentally different than they are. A quick way to neutralize this self-serving logic is to ask the class, “how many of you think this is true? Show of hands who thinks that ‘people are gullible and obedient’?” Almost every hand in the class goes up. “Okay, now how many of you think you are gullible and obedient?” Not a single hand goes up. “Oh, so this is something ‘people do’ but none of you do it. Huh, that’s strange.” This is a great launching point for a discussion of the fundamental attribution error.

*The fundamental attribution error comes from social psychology (as far as I know). So it kinda makes sense that it’s not featured in a 101 text.

If there is one thing The Daily Show does better than anyone, it’s expose hypocrisy. This is helpful when teaching conflict theory. One of the central tenants of conflict theory (and hegemony more directly) is that those in power use their influence to cast their behaviors in the best light possible. These powerful actors similarly use the media to cast the least powerful in society in the worst possible light. (Note: I spoke about this last year, read that post here)

J. Stewart and the Daily Show gang’s coverage of the Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker’s attempt to abolish the teachers union’s ability to collectively bargain has been particularly on point. Stewart effectively juxtaposes the cable news media’s presentation of the “lazy, fat cat, undeserving teachers” making $50k a year to the “job creating Wall Street executive” making $250+ who deserve a continuation of the Bush tax break. Even more damming is the video of the same people saying one thing for the rich and the exact opposite for teachers. While Stewart’s brashness is not conducive to everyone’s teaching style, I find my students have a better understanding of conflict theory/hegemony after watching clips like this.

Here’s a bonus clip that shows how the media rejoice when big banks like J.P. Morgan and Goldman Sacs rake in the dough because the Fed is literally giving them the money to sell to the US government to pay back the TARP money we gave them. While students may need some help following this cycle, they are appalled to learn how the big banks receive this government handout.

<!– "I want you to stand perfectly still & expressionless for 15 minutes outside the union," that is what I told my 262 soc101 students yesterday as I surprised them with an activity called "Doing Nothing". The Doing Nothing activity, originally designed by Karen Bettez Halnon, is a modification on the classic break-a-norm activity.

I use this activity to teach norms, deviance, and Goffman’s The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Students feel first hand the anxiety of norm violations. They experience being stigmatized and being labeled by others as crazy, creepy, or even scary. Instead of norms, deviance, and Goffman being abstract sociological concepts they become real experiences.

Advantages to Doing Nothing as a Class:

Break a norm in public. That is arguably the oldest sociology activity in the book. Problem is, most students don’t actually do it; opting instead to write the paper based on what they imagine the experience would be like. When this happens your break-a-norm activity turns into a short fiction assignment. Doing Nothing as an entire class allows you to verify students had the experience.

Another benefit of Doing Nothing as a class is you can provide a safe and secure environment for your students.

PUBLIC SOCIOLOGY – MAKE IT REAL – MAKE IT FOR ALL –>

Want to teach your students about norms, deviance, and the social construction of reality in a way that they’ll never forget? Try Doing Nothing, literally. Have your students silently stand in a public place for 15 minutes with absolutely no expression on their face. If anyone approaches them they are to reply to any and all questions by saying, “I am doing nothing.”

Students laugh when they hear the directions. Anxiety washes over them as they take their places. They struggle to contain nervous laughter and their fight or flight instinct that is screaming RUN in their head. All of a sudden those abstract concepts, deviance, norms, stigma, all become uncomfortably real. Students learn with their own two eyes how people react to non-conformers- to deviants. This is lived sociology.

Doing Nothing is not my own idea. Karen Bettez Halnon (2001) in Teaching Sociology outlined how she had her students individually do nothing in a public place for 30, of what I assume must have been excruciating, minutes. All I’ve done here is tweak her idea and amplify it to an extreme.

I figured if I have a class of 262 students why not put it to use. One person doing nothing is strange, but 262 students doing nothing is a sight to behold. Also, doing the activity as a class allowed me to verify* it was carried out and that students safety** was maintained.

Public Sociology:

Despite sociology being inherently social, it is surprising how rarely we use the public in the instruction of sociological concepts. I am most proud of how interactive this learning experience was. Students learned by doing (and at a grand scale).

Now, with our YouTube video, the students and I are trying to teach as many people as possible the sociological lessons we learned yesterday. My hope is that my students will see how their actions started a small social movement and created change and learning in others. I plan on using this as an example of how they can change the world around them. If you teach for social justice, if you hope to inspire your students to do more than just memorize some facts for a test, then we have to find ways to role model, or better yet provide a platform for, creating social change in our communities.

As a final note, it would mean a lot to me if you would take the time to watch the video above and pass it along to someone you think would enjoy it. The more people who watch the clip the more my students will feel capable and empowered to create social change. I have loved giving away as much as I possibly could over the last year and now I am asking for one small favor in return. Five minutes of your life to watch the clip, send it to someone else, Tweet it, post it on Facebook, etc.

Thank you,

Nathan

Event Logistics:

If you’re going to do anything with 262 people you’re going to need help and a lot of planning ahead. I recruited 11 student volunteers to help me with maintaining safety and crowd control. I created a handout to communicate to the volunteers what their responsibilities were (download it here).

I also created a set of concise and explicit lecture slides that visually explained the directions for the activity (see below | Download them here). Note that students were required to participate, but not to be video recorded. Students had the option to do the activity in another location away from cameras, but none of my 262 students chose not to participate (which was a delightful surprise). Students who were going to be recorded had to sign an image release and consent form.

Doing nothing

View more presentations from Nathan Palmer

*Break a norm in public. That is arguably the oldest sociology activity in the book. Problem is, most students don’t actually do it; opting instead to write the paper based on what they imagine the experience would be like. When this happens your break-a-norm activity turns into a short fiction assignment. Doing Nothing as an entire class allows you to verify students had the experience.

**As Bettez Halnon mentions in her Teaching Sociology article, students are left vulnerable in a public place if you ask them to do this activity alone. Every time I have done this activity I have found that passersby will try to coax a response out of students by touching them in some way. Typically this is a simple poking on the nose or lifting up an arm and then letting it fall, but I’ve seen students attempt to pull on students coats and backpacks. I absolutely would not do this activity without supervising the event myself. Along these same lines, I also instruct my students that if at any moment they feel unsafe in anyway they are to discontinue the activity and return to the classroom.

Maybe it’s the Just World Hypothesis or maybe it’s the dichotomization of racism, but for whatever reason, students are quick to claim they’ve been cured of racism.[1] Racism, it would appear, is a big problem… for other people. Or older generations. Or other parts of the country (like in the South). According to many students, racism is a problem, to be sure, but it’s not a problem for them.

I’ve talked at length here at SociologySource about the need to teach our students that racism is more than overt hateful acts committed by ultra bigots. Racism (and all prejudice and discrimination for that matter) need to be conceptualized as problems “good, moral, and honest” people have. Furthermore, when we conceptualize all prejudice and discrimination as being big events carried out by mean people, we marginalize the day-to-day experiences of socially non-dominant peoples.

The concept of microaggressions helps my students understand the more everyday side of racism. Microaggressions are defined by Solórzano et al. (2002) as, “subtle verbal and non-verbal insults directed at non-whites, often done automatically or unconsciously” (Pp. 17)[2]. This conceptual framework also does a great job of separating the intent of an action from the impact that action has.

Franchesca Ramsey’s Sh*t White Girls Say About Black Girls is one of the best illustrations of the microaggressions concept[3]. Ramsey satirizes white microaggressions in a way that is both painfully funny and painfully honest.[4]

When this video came out it quickly went viral and then was parodied by a number of white actors who thought it was racist to point the finger at white women. The article “Not Everyone’s Laughing At ‘Sh*t White Girls Say To Black Girls’” by Tami Winfrey Harris at Clutch magazine does a fantastic job of reporting the backlash and critiquing the false equivalence of microaggressions targeted toward whites. Winfrey Harris uses microaggressions to analyze both Ramsey’s video and the backlash to it in her article and draws attention to the blog Microaggressions.com. This is a fantastic site of user submitted stories of microaggressions they have experienced in their everyday lives.

Pairing Ramsey’s video, Winfrey Harris’s article, and Microaggressions.com seemed like too potent a pedagogical opportunity to not use in my classes. I put together a quick written assignment for students to do before coming to class that will hopefully start a vibrant discussion on racism and microaggressions (Download it Word | pdf). Unlike most of the things I post here at SociologySource, I haven’t tried this one yet, but I plan to this fall.

If you’ve taught microaggressions before or if you have any suggestions/additions to this project hit me up on Twitter @SociologySource, on our Facebook page, or email me at Nathan @ SociologySource . Com.

-

To be clear, I do mean all students. While white students have been, in my experience, more likely to celebrate the end of racism, I have found that students of all racial ethnic groups espouse that same idea. Some students only argue that they are cured of racism and others argue that racism is no longer a real social problem. ↩

-

Solórzano, Daniel G. and Delgado Bernal, Dolores 2001 ‘Examining

transformational resistance through a Critical Race and LatCrit Theory Framework: Chicana and Chicano students in an urban context’, Urban Education, vol. 36, no. 3. pp. 308–42 ↩ -

The video is fantastic, but it’s not for everyone’s teaching style. I would also be more inclined to show it to an upper level or graduate level class. If you are going to show it to an intro to sociology class, I would highly recommend a large amount of time for class discussion and decompression. ↩

-

Do keep in mind that I am neither Black nor a woman, but I have heard something similar to most of the statements Ramsey makes. The video rings true to me. Just saying. ↩

When I was a kid my school had “multi-cultural” day- usually in February. It was our annual conversation about MLK and the Civil Rights movement. I remember asking my 5th grade teacher something to the effect of, “if today is ‘multi-cultural’ day, what are all the rest of the days?” I’ve been an “annoying sociologist” my entire life.

On these “multi-cultural days” we were taught one thing more than anything else, “don’t be racist”. Racism, I was told, was a problem had by ignorant meanies. Racism was an end state. It was something you were; like a title. This, as I’ve discussed before, is the dichotomization of racism.

A week or so ago, friend of the site Paula Teander or @sober_sociology sent me this TED talk by Jay Smooth about the dichotomization of racism (he doesn’t use those words). I like this video so much that I will certainly be using it in my 101 classes from now on.

He mentions in his talk another of his videos “How to Tell People They Sound Racist”:

What They Don’t Teach On Multi-Cultural Days

These are great and I totally plan on using them, but as a sociologist, I always want my students to know that while individual racism is terrible, institutional racism has a much bigger impact on the daily lives of people in our society.

That’s what they don’t teach you during “multi-cultural days”. When racism is discussed as an individual problem (whether it be an end state or a single act as Mr. Smooth suggests), it overlooks how racism can exist without any one person being actively and overtly racist. After we talk about racial institutional discrimination in housing, employment, banking, education, etc. I ask my students, “If I could wave a magic wand and make everyone never think, act, or speak in a racist manner ever again, would racial inequality evaporate?” The answer comes easily to my class.

The best lessons are the ones your students teach themselves. You can’t tell students anything, but you can give them the eyes to see their own behavior from a new light and they will teach themselves more than you could’ve ever dreamed.

I love gender because it’s written all over our bodies. Students come into class doing gender. You only need to draw their attention to their own gendered presentations and ask them to “see the familiar as strange”. That’s easier said than done.

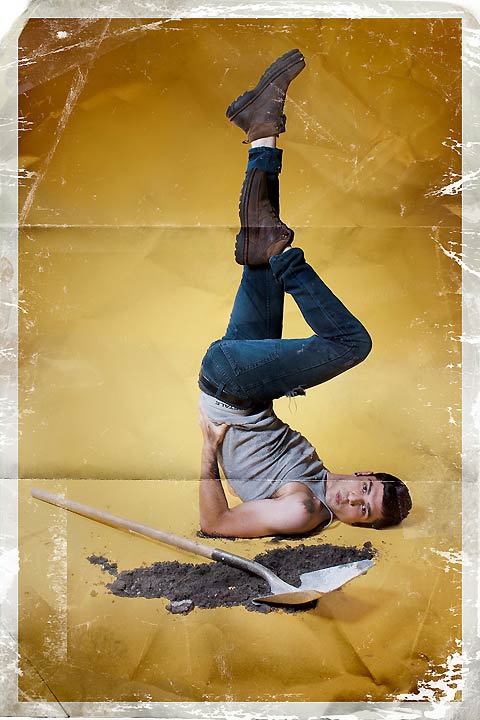

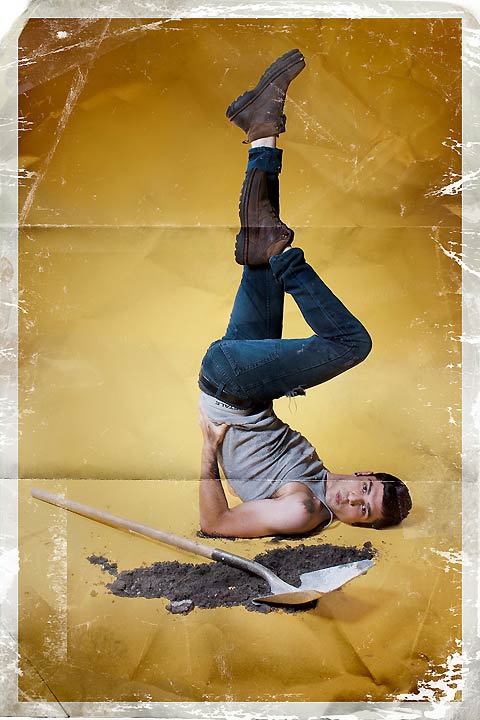

When students see a “failed performance”[1] of gender the intentionality of their own “successful” gender performance comes into stark contrast.

Photographer Rion Sabean did a collection of “Men-Ups” where men were shown in poses that are stereotypically reserved for women in Pin-Up calendars. The photos are men, doing “manly” things, but they are posed in gender opposite ways.

Support Rion by purchasing a Men-Up calendar!

After my student’s have been shook awake and their own gender performance is drawn into the light, I ask them to help me come up with a list of “gender rules”. I split the room and half address how a person becomes a “girly girl” and the other addresses how a person performs as a “manly man”[2]

Below are some slides I put together to highlight gender performances and media presentation of the masculine and the feminine.

The Codes of Gender

The Media Education Foundation has a great film that addresses gender and imagery better than any other I’ve seen. I’ve always liked Sut Jhally’s work, but this one is his best since Advertising and the End of the World.[3] Pairing this video with the Men-Ups calendar images is a powerful one two punch.

I top all of this gender imagery with an assignment that ask my students to go find a photograph of men and women in stereotypic poses and critically analyze the image. You can find those directions here. Enjoy.

Footnotes:

-

This is not a moral judgment, but a reflection of many students own perceptions. I do not contend that there is a right, appropriate, or “normal” gender performance, but rather I contend that many students perceive there to be one. All gender expressions are equally valid and equally deserving of respect. Do your gender how you see fit. ↩

-

I tell my students to notice how we do gender with terms like “girly girl” and “manly man”. To be masculine is to be mature, but to feminine is to be infantalized according to the dominant stereotype. My students laugh when I ask them to consider if I asked them to tell me how to become a “womanly woman” or a “boyish boy”. ↩

-

Dr. Jhally if you are listening. Please please update this film. I’d love to show it in my classes, but the ads are comically out of date now. ↩

“I thought this class was going to be about the environment, but we keep talking about illegal immigrant workers.” is a statement one of my students years ago made in my environmental sociology class. The social inequality we see in a society is reflected in and reproduced by the the maltreatment of the environment. This is the foundational idea I want my students in environmental sociology to learn. However, drawing the connection between the two can at times seem counter intuitive to students.

I love the film Food, Inc. because it addresses how intertwined our social realities are to our environmental realities. The video pairs the exploitation of low level workers in the food industry with the tragic conditions animals are raised and slaughtered in. At one point in the film someone says that corporate food producers treat workers exactly like the treat their animals. Both will be gone soon, so it just easier to design the system to acquire them quickly, use them up, and discard them.

We see in the film how large food corporations use their power to shape the government regulations that are supposed to oversee their industry and protect consumers. Students learn that in some states legislation has been proposed that would make it a felony to snap a photo of a industrial food operation and how in all states its a crime to speak out against food producers under the “veggie-libel laws”. This film is perfect for any class that discusses Mills’s The Power Elite or anything from Marx.

While the film paints a grave picture of our current food situation in America, it’s not doom & gloom. Throughout the film I found myself thinking, “why are we producing food like this? This makes no sense.” I’ve yet to have a class where students were perplexed by the rampant irrationality of rationality on display in the entire industrial food production system. The film closes with actions that people can take and tells the viewer, “You have a vote on this system three times each day”. More than any issue I present in my environmental sociology class my students really seem motivated and confident they can affect a change. In particular students agreed with the CEO of Stonyfield Farm Organics who says in the film, consumers have far more sway on what grocers sell than they may perceive.

I created a viewing guide for my students to fill out as they watch the film (download it here) and a short writing assignment that focuses on the connection between the social and natural worlds (grab it here). Food, Inc is available on Netflix streaming for free and should mandatory viewing for all sociologists.

The photo above is on the projector screen when I turn and start class by asking, “What is this a sign for? That is, where would we see this sign and why would it be put up in the first place.” After some bewildered looks students state the obvious, “those signs are along the border.” “The border of Georgia1“I quickly ask. Students laugh softly, “No the Mexican border”. “Why?” I prod them. “Because that’s where all the illegals come from.” “Oh, I see,” I turn and point to the screen in the front of the room and continue, “Who can tell me what ‘social problem’ if any this sign could be associated with. That is, what name would we give to the social problem this sign reflects.” A chorus of voices says, “Illegal Immigration”.

I nod and say, “What if I told you that this social problem you call ‘Illegal Immigration’ is part of a grand story that powerful people in society have been trying to get you to believe? What would you say?” After a healthy pause I follow, “Could anyone in the class tell me the story of ‘Illegal Immigration’?” The silence in the room becomes deafening as my students turn and look around the room with perplexed looks on their faces. “Well then I’d like you to do some research and come back to me next week and tell me if you’ve figured out the story.”

The Research on “Illegal Immigration”

“Illegal Immigration” or undocumented immigration, as I’ll be referring to it, is a hot button issue that has been consistently in the news media for as long as I can remember. However the issue seemed to hit another peak in public attention when Arizona passed a highly punitive state law to enforce federal immigration policy. This was only furthered by the passing of copycat laws in Alabama and Georgia (just to name a few). Given all the media attention there is a lot of great resources out there for teaching the controversies around this social problem.

My students love it when I can pair academic sources with popular media. They really love it when we use multiple mediums. I’ve created an “immigration media collection” that includes the following. The collection is designed to present conflicting arguments from the opponents of and supporters of undocumented immigrants.

- “My Life as an Undocumented Immigrant” by Jose Antonio Vargas (Story featured in The New York Times Magazine).

- An audio podcast of a NPR Fresh Air Interview with Vargas & Mark Krikorian of the Center for Immigration Studies. Vargas goes into further detail in his half of the podcast and Krikorian talks about why he feels Vargas should be deported.

- A CBS Evening News report on how Georgia farmers are struggling to farm without undocumented immigrants.

- An episode of 30 Days where a Minute Man lives with an undocumented family. See below:

30 Days: Immigration from MacQuarrie-Byrne Films on Vimeo.

I pair all of these popular media with the chapter on immigration from our course textbook and it creates a powerful pedagogical tool. Students seemed to be really thinking about the issues deeply. Many students said it was only after they watched the video and read Vargas’s story that they wanted to know more about the facts and sociological research surrounding undocumented immigration. So, at least in this case, popular media created a hunger for scholarly research.

The Stories We Tell About Undocumented Immigration

After spending a week on undocumented immigration my students were primed to break down the narrative behind the social problem. When I asked, “What is the story or stories well tell about ‘illegal immigration’ in the United States?” My students quickly pointed to the border and that image I’d used to start our entire discussion. “The border isn’t the only problem.” I asked them to tell me more. “Around half of immigrants over stay their visas, so we could build a wall to the heavens and it wouldn’t end the problem of undocumented immigration.” I was impressed.

“What else,” I asked. There was a long pause before someone said, “The story we tell is only half the story.” With a prompt from me the student continued, “We only talk about the undocumented immigrants and we rarely if ever talk about the corporations that employ them.” “Bingo,” I replied. For the rest of the class we talked about conflict theory’s argument that powerful social actors use their influence to define social problems as being the responsibility or fault of the least powerful in society. “It’s all in the name,” one of my students said. “‘illegal immigration’ says it all. The problem is the ‘illegals’ not the employers who bring them here.” “Right,” I began, “we call it ‘illegal immigration’ and not ‘non-citizen exploitation’. Both names are apt, but as a society we’ve been convinced to focus on the former.”

While my students were feeling particularly anti-corporation I asked them if they play a role in undocumented immigration. Multiple heads shook left to right and someone mustered a, “No.” “What sectors of our economy do undocumented immigrants work in? That is, what jobs do they tend to have?” Quickly a list forms, “Farming, meat packing, factory work, landscaping, and housework,” were shouted out. Then I asked, “If undocumented laborers are paid an unfair wage for harvesting food or manufacturing products, does this not make them cheaper?” The obvious answer came easily. “Do you think that any of you have purchased any of these products made cheaper by undocumented immigration?” No one said a word, but heads slowly nodded. “So in that case all of you have directly benefited from undocumented immigration. You’ve had more money in your pocket because someone didn’t get paid what they should have, right?” The answer didn’t come as easy this time.

What I want my students to learn is that the story we tell about undocumented immigration is a simple one that blames only one group; the group with the least social power. In reality undocumented immigration is terribly complex and each of us in the United States has been either a victim or benefactor of harsh state and federal immigration policies. Once students accept that the world is far more complex than we are told it is on the news we can start to develop their sociological imagination.

Environmental sociology is great because it focuses on the biggest social system we have, the natural environment. The natural environment is at the center of culture, the economy, and every other social institution in one form or another. To understand environmental sociology is to understand social systems. The Story of Stuff is the best video I’ve found for explaining how individual actions, social systems, and the natural environment all intertwine. The video is just 21 minutes and available online making it an excellent resource to use in class or as a homework assignment.

If you teach Marx you need to show this video to your students. I’ve spent multiple classes trying to explain how capitalism (a linear system) and the natural environment (a finite resource) can not coexist long term, but it wasn’t until my students watched this video that they truly understood what Marx was trying to say. Furthermore, students seem to grasp how capitalism generated inequality and social injustice both in the U.S. and globally.

I’ve also used this video to teach my students about the difference between what we value and what we spend our money on. I’ll start class by asking students to write down a single item they possess that could never be replaced if it was lost. The item has to be something they would be heartbroken if they lost it forever. In the past students have written things like family photos, something a loved one passed on to them, or something mundane that holds a great deal of sentimental value to them because of who they were with when they first got it. After we watch The Story of Stuff I ask the students to flip the paper over and write down what items they spend most of their discretionary money on. Students write down things like clothes, video games, and smart phones. Then we start a class discussion about why the sentimental things we value are not the things we spend most of our money on.

This video is the gift that keeps on giving. Even if you don’t teach environmental sociology, this video would be a great inclusion for an Intro to Sociology class, a Social Problems class, and any class dealing with global issues or inequality.

The fundamental attribution error is so central to learning sociology that it astonishes me that I’ve never seen it covered in a Soc 101 text*. The fundamental attribution error is the idea that each of us as an individual is biased toward viewing our behaviors within the context of our circumstances. However, when we view the behaviors of others we attribute their behaviors to who they are as a person or to their character. The classic example is speeding.

To begin a class discussion on the fundamental attribution error I ask my students to think about the last time they broke the speed limit. Not like 5 miles an hour over, but like really really broke the speed limit. After a moment I ask, “So why were you speeding?” Students describe how they typically don’t recklessly speed unless there is some dire need to get somewhere fast. Students talk about being fired if they are late to work one more time, sleeping through an alarm and being late to a final or midterm, or speeding to catch a flight. Many times students start their explanations by saying, “I typically don’t speed, but…” When asked why they speed students provide a litany of circumstantial reasons for their “unusual” behavior.

I then ask students to think about the last time they were driving and someone blew by them or was weaving through traffic recklessly. After they collect this memory, I ask them how they feel about the speeding driver. “I typically yell, ‘you ___ hole!'” one of my students said this semester. Students go on to describe how they feel the reckless driver is a danger to society and they need to be stopped. Student describe speeders as fundamentally different people from them. They have a character flaw that makes them speed. There is almost always no discussion of how the other speeders may be experiencing circumstances similar to the times that students recalled speeding. Basically what pans out every time I have this discussion is that, students speed because of unique circumstances, but others speed because of who they are.

We can see the fundamental attribution error all over the place in sociology. It’s present in almost every stereotype. We see it in the criminal justice system. But where I experience the fundamental attribution error the most is in discussions of inequality. Students can go on and on about how they’re loved ones work extremely hard and still can’t get themselves out of poverty, but they also go on and on about how they know so many poor people who, unlike their loved ones, are lazy and unwilling to even try to live independent of government aid. I frequently hear a statement like this, “It makes me so mad to see all these people who live off of welfare whining about being broke when they aren’t even looking for work or trying to be independent. When my family was on welfare we used it because we had to and as soon as we could get off of it we did.” Statements like this show how students place their families use of welfare within the context of their circumstances, but they refuse to extend the same to other families on welfare. The character of these other families are fundamentally different from theirs. When we talk about empirical research that shows that the majority of welfare recipients only receive aid for a short period of time and then leave the programs as soon as they can, students seem perplexed. They tell me stories of people they saw picking up welfare checks in Cadelac Escalades. They tell me that despite my empirical evidence to the contrary, most people “abuse welfare” and their family was one of the rare exceptions. Knowing that this discussion is almost certainly coming, I start the semester with a discussion of the fundamental attribution error and I’ve found that students are increasingly willing to accept the empirical evidence.

Discussions of authority and obedience are another area ripe for the fundamental attribution error. In my class we watch a clip about the Stanford Prison experiment, read about Millgram’s electrocution experiments, and the like. Students learn about all these examples of obedience with disbelief. Students almost always say something like, “Well all this research shows is there are some gullible and obedient people out there.” Here again is the fundamental attribution error. My students believe that these “obedient people” are fundamentally different than they are. A quick way to neutralize this self-serving logic is to ask the class, “how many of you think this is true? Show of hands who thinks that ‘people are gullible and obedient’?” Almost every hand in the class goes up. “Okay, now how many of you think you are gullible and obedient?” Not a single hand goes up. “Oh, so this is something ‘people do’ but none of you do it. Huh, that’s strange.” This is a great launching point for a discussion of the fundamental attribution error.

*The fundamental attribution error comes from social psychology (as far as I know). So it kinda makes sense that it’s not featured in a 101 text.

If there is one thing The Daily Show does better than anyone, it’s expose hypocrisy. This is helpful when teaching conflict theory. One of the central tenants of conflict theory (and hegemony more directly) is that those in power use their influence to cast their behaviors in the best light possible. These powerful actors similarly use the media to cast the least powerful in society in the worst possible light. (Note: I spoke about this last year, read that post here)

J. Stewart and the Daily Show gang’s coverage of the Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker’s attempt to abolish the teachers union’s ability to collectively bargain has been particularly on point. Stewart effectively juxtaposes the cable news media’s presentation of the “lazy, fat cat, undeserving teachers” making $50k a year to the “job creating Wall Street executive” making $250+ who deserve a continuation of the Bush tax break. Even more damming is the video of the same people saying one thing for the rich and the exact opposite for teachers. While Stewart’s brashness is not conducive to everyone’s teaching style, I find my students have a better understanding of conflict theory/hegemony after watching clips like this.

Here’s a bonus clip that shows how the media rejoice when big banks like J.P. Morgan and Goldman Sacs rake in the dough because the Fed is literally giving them the money to sell to the US government to pay back the TARP money we gave them. While students may need some help following this cycle, they are appalled to learn how the big banks receive this government handout.

<!– "I want you to stand perfectly still & expressionless for 15 minutes outside the union," that is what I told my 262 soc101 students yesterday as I surprised them with an activity called "Doing Nothing". The Doing Nothing activity, originally designed by Karen Bettez Halnon, is a modification on the classic break-a-norm activity.

I use this activity to teach norms, deviance, and Goffman’s The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Students feel first hand the anxiety of norm violations. They experience being stigmatized and being labeled by others as crazy, creepy, or even scary. Instead of norms, deviance, and Goffman being abstract sociological concepts they become real experiences.

Advantages to Doing Nothing as a Class:

Break a norm in public. That is arguably the oldest sociology activity in the book. Problem is, most students don’t actually do it; opting instead to write the paper based on what they imagine the experience would be like. When this happens your break-a-norm activity turns into a short fiction assignment. Doing Nothing as an entire class allows you to verify students had the experience.

Another benefit of Doing Nothing as a class is you can provide a safe and secure environment for your students.

PUBLIC SOCIOLOGY – MAKE IT REAL – MAKE IT FOR ALL –>

Want to teach your students about norms, deviance, and the social construction of reality in a way that they’ll never forget? Try Doing Nothing, literally. Have your students silently stand in a public place for 15 minutes with absolutely no expression on their face. If anyone approaches them they are to reply to any and all questions by saying, “I am doing nothing.”

Students laugh when they hear the directions. Anxiety washes over them as they take their places. They struggle to contain nervous laughter and their fight or flight instinct that is screaming RUN in their head. All of a sudden those abstract concepts, deviance, norms, stigma, all become uncomfortably real. Students learn with their own two eyes how people react to non-conformers- to deviants. This is lived sociology.

Doing Nothing is not my own idea. Karen Bettez Halnon (2001) in Teaching Sociology outlined how she had her students individually do nothing in a public place for 30, of what I assume must have been excruciating, minutes. All I’ve done here is tweak her idea and amplify it to an extreme.

I figured if I have a class of 262 students why not put it to use. One person doing nothing is strange, but 262 students doing nothing is a sight to behold. Also, doing the activity as a class allowed me to verify* it was carried out and that students safety** was maintained.

Public Sociology:

Despite sociology being inherently social, it is surprising how rarely we use the public in the instruction of sociological concepts. I am most proud of how interactive this learning experience was. Students learned by doing (and at a grand scale).

Now, with our YouTube video, the students and I are trying to teach as many people as possible the sociological lessons we learned yesterday. My hope is that my students will see how their actions started a small social movement and created change and learning in others. I plan on using this as an example of how they can change the world around them. If you teach for social justice, if you hope to inspire your students to do more than just memorize some facts for a test, then we have to find ways to role model, or better yet provide a platform for, creating social change in our communities.

As a final note, it would mean a lot to me if you would take the time to watch the video above and pass it along to someone you think would enjoy it. The more people who watch the clip the more my students will feel capable and empowered to create social change. I have loved giving away as much as I possibly could over the last year and now I am asking for one small favor in return. Five minutes of your life to watch the clip, send it to someone else, Tweet it, post it on Facebook, etc.

Thank you,

Nathan

Event Logistics:

If you’re going to do anything with 262 people you’re going to need help and a lot of planning ahead. I recruited 11 student volunteers to help me with maintaining safety and crowd control. I created a handout to communicate to the volunteers what their responsibilities were (download it here).

I also created a set of concise and explicit lecture slides that visually explained the directions for the activity (see below | Download them here). Note that students were required to participate, but not to be video recorded. Students had the option to do the activity in another location away from cameras, but none of my 262 students chose not to participate (which was a delightful surprise). Students who were going to be recorded had to sign an image release and consent form.

*Break a norm in public. That is arguably the oldest sociology activity in the book. Problem is, most students don’t actually do it; opting instead to write the paper based on what they imagine the experience would be like. When this happens your break-a-norm activity turns into a short fiction assignment. Doing Nothing as an entire class allows you to verify students had the experience.

**As Bettez Halnon mentions in her Teaching Sociology article, students are left vulnerable in a public place if you ask them to do this activity alone. Every time I have done this activity I have found that passersby will try to coax a response out of students by touching them in some way. Typically this is a simple poking on the nose or lifting up an arm and then letting it fall, but I’ve seen students attempt to pull on students coats and backpacks. I absolutely would not do this activity without supervising the event myself. Along these same lines, I also instruct my students that if at any moment they feel unsafe in anyway they are to discontinue the activity and return to the classroom.