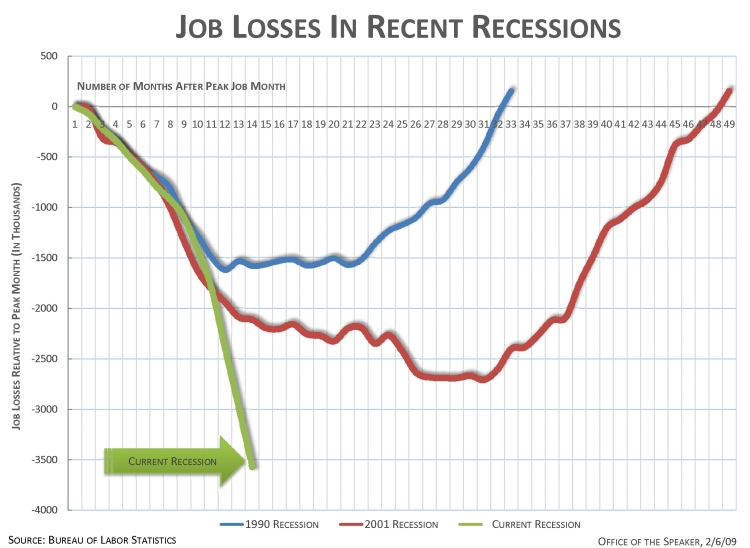

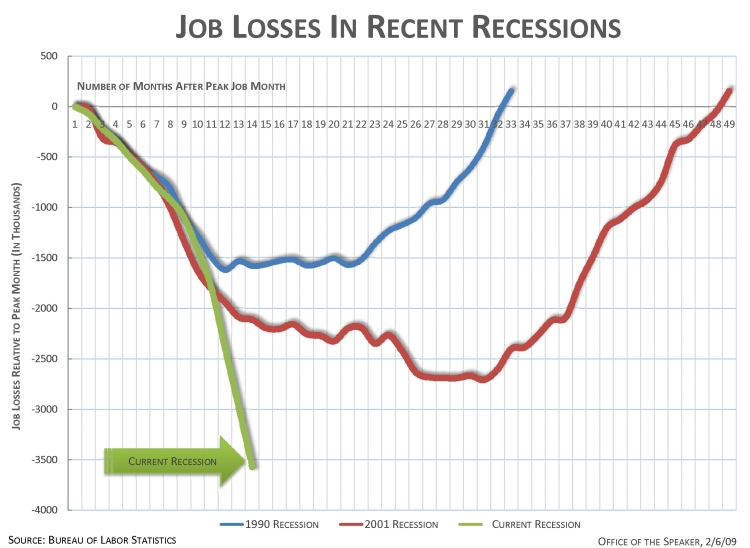

This graph, based on U.S. Bureau of Labor statistics and current as of February 6th, compares the number of jobs lost during the 1990 (blue), 2001 (red), and current (green) recessions:

Found at The Daily Kos thanks to Jerry A.

This graph, based on U.S. Bureau of Labor statistics and current as of February 6th, compares the number of jobs lost during the 1990 (blue), 2001 (red), and current (green) recessions:

Found at The Daily Kos thanks to Jerry A.

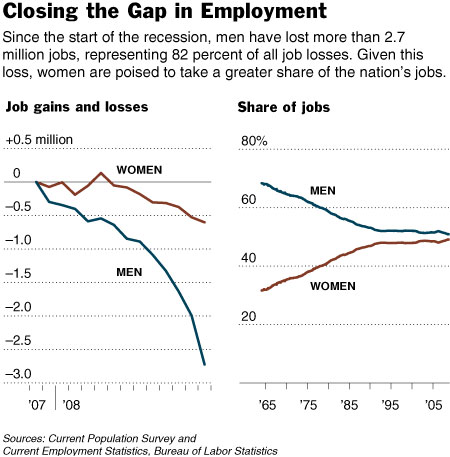

This week in the New York Times, Catherine Rampell explained how the recession was affecting the ratio of female to male workers:

The proportion of women who are working has changed very little since the recession started. But a full 82 percent of the job losses have befallen men, who are heavily represented in distressed industries like manufacturing and construction. Women tend to be employed in areas like education and health care, which are less sensitive to economic ups and downs, and in jobs that allow more time for child care and other domestic work.

Here are the results:

Excluding farm workers and the self-employed, women held 49 percent of the nation’s jobs as of November. Including farm workers and the self-employed, women held 47 percent of jobs.

But, Rampell reminds us:

Women may be safer in their jobs, but tend to find it harder to support a family… Women are much more likely to be in part-time jobs without health insurance or unemployment insurance. Even in full-time jobs, women earn 80 cents for each dollar of their male counterparts’ income…

If the recession continues as it has, the U.S. workforce may soon be majority female.

See also this post on job segregation.

Thanks to Captain Crab for letting me know about this fun 20-minute video by Annie Leonard called The Story of Stuff. It it, using animation, she explains how “[f]rom its extraction through sale, use and disposal, all the stuff in our lives affects communities at home and abroad.” Basically it’s about the externalized costs that allow us to get things for $1.99 at our local big-box store:

Found at The Story of Stuff.

NOTE: As several commenters have pointed out, this video is definitely a simplification–it is, after all, a very brief overview of an extremely complex process. The video still provides a fairly accurate portrayal of some concerns expressed by critics of globalization, despite the simplifications.

One commenter in particular argues that the statistics used in the video are flawed or even entirely made up. I really have no way to judge that one way or the other, not being an expert on this. At the website for The Story of Stuff, there are citations for all of the numbers used, so if you’re really interested in that, you might want to look more fully into where the data came from. Again, I can’t take a real stance here one way or the other because this isn’t my area of expertise; the data might be flawed, but the commenter doesn’t provide other data to contradict it. It might make for an interesting discussion on the use of data and why people with different views on globalization might use different numbers. You take students through it and ask “What’s useful here? What statistics might be inaccurate? Why might they be presented that way? Why is it possible to come up with statistics that say completely different things about the same issue?”

Click here for a discussion of how one Professor uses it in a Rhetoric and Writing class.

In this video, from the New York Times, Nicholas Kristof argues that sweatshops are, despite their drawbacks, the best option for many people in many places… and that anti-sweatshop activists should keep that in mind.

Now and again, I hear that college graduates entering the workforce today, both male and female, offer a new set of challenges to employers. Notably, a sense of entitlement to high pay and excellent benefits and a poor work ethic. I have no idea if this is true. However, over at MultiCultClassics, Highjive posted an ad for a seminar that purports to teach employers to handle “Millennials”. It’s similar to a post that Gwen put up about advice to employers for working with women when they initially entered the paid workforce in large numbers.

Text:

There’s a new professional entering the workforce today—one who is different in attitude, behavior, and approach to both work and career. Discover where they are coming from through this two-day seminar at Loyola, which helps bridge the gap between Baby Boomer managers and their younger cohorts, the Millennials.

Found via Digg. Though I can’t vouch for the authenticity of the letter (found here), it is rather interesting.

Text:

Miss Mary T. Ford

Searcy,

ArkansasDear Miss Ford,

Your letter of recent date has been received in the Inking and Painting Department for reply.

Women do not do any of the creative work in connection with preparing the cartoons for the screen, as that work is performed entirely by young men. For this reason girls are not considered for the training school.

The only work open to women consists of tracing the characters on clear celluloid sheets with India ink and filling in the tracings on the reverse side with paint according to the directions.

In order to apply for a position as “Inker” or “Painter” it is necessary that one appear at the Studio, bringing samples of pen and ink and water color work. It would not be advisable to come to Hollywood with the above specifically in view, as there are really very few openings in comparison with the number of girls who apply.

Yours very truly,

WALT DISNEY PRODUCTIONS, LTD.

Naama Nagar sent in these images from a “booklet that was intended to assist male bosses in supervising their new female employees at RCA plants,” according to the National Archives, Southeast Region (found via Michael Zilberman’s history blog; sorry it’s in Hebrew):

Text:

When you supervise a woman…Make clear her part in the process or product on which she works. * Allow for her lack of familiarity with machine processes. * See that her working set-up is comfortable, safe and convenient. * Start her right by kindly and careful supervision. * Avoid horseplay or “kidding”; she may resent it. * Suggest rather than reprimand. * When she does a good job, tell her so. * Listen to and aid her in her work problems.

Text:

Finally–call on a trained woman counselor in your personnel department…to find out what women workers think and want. * To discover personal causes of poor work, absenteeism, turnover. * To assist women workers in solving personal difficulties. * To interpret women’s attitudes and actions. * To assist in adjusting women to their jobs.

Text:

When you put a woman to work…Have a job breakdown for her job. * Consider her education, work experience and temperament in assigning her to that job. * Have the necessary equipment, tools and supplies ready for her. * Try out her capacity for and familiarity with the work. * Assign her to a shift in accordance with health, home obligations and transportation arrangements. * Place her in a group of workers with similar backgrounds and interests. * Inform her fully on health and safety rules, company policies, company objectives. * Be sure she knows the location of rest-rooms, lunch facilities, dispensaries. * Don’t change her shift too often and never without notice.

These are interesting from a gender perspective, of course, but they’re also sort of fascinating for what they tell us about changing assumptions about what the workplace is (or should be) like. While there were many problems with the World War II (and post-war) workplace, there was also a certain assumption that companies would take care of their employees to some degree in return for employees’ loyalty and hard work. This comes through in instructions such as “Assign her to a shift in accordance with health, home obligations and transportation work” and “Don’t change her shift too often and never without notice.” The idea is that workplaces, including factories, should think about their employees’ lives and how their work schedules fit in with their other obligations, as well as provide things like dispensaries. Now, I’m sure many companies didn’t actually meet these ideals, but this booklet sent out to managers at least acknowledges that they exist. Today, most workplaces don’t even pretend to aspire to such ideals. While some privileged white-collar workers may have options like flexible hours or working from home, many workers find that their hours and schedules change from week to week, making it difficult to arrange child care or work around other obligations. McDonald’s is well known for making workers sign out during slow periods during their shift to keep payroll down (workers are expected to be available, however, should business pick back up) and Wal-Mart has been sued for failing to pay overtime or for asking workers to work off the clock, again to reduce payroll costs.

So these might be useful for a discussion of work and what we expect from the worker-employer relationship. Is it simply a contractual financial exchange? Do workers and employers owe each other anything besides an hour of work and an hour of pay at the agreed-upon price? How have employers pushed concerns about schedule disruptions and payroll reductions off on workers, forcing them to accommodate the company’s needs?

Thanks, Naama!

Laura Agustin, author of Sex at the Margins: Migration, Labour Markets, and the Rescue Industry, asks us to be critical consumers of stories about sex trafficking, the moving of girls and women across national borders in order to force them into prostitution. Without denying that sex trafficking occurs or suggesting that it is unproblematic, Agustin wants us to avoid completely erasing the possibility of women’s autonomy and self-determination.

About one news story on sex trafficking, she writes:

…[the] ‘undercover investigation’, one with live images, fails to prove its point about sex trafficking… reporters filmed men and women in a field, sometimes running, sometimes walking, sometimes talking together.

…I’m willing to believe that we’re looking at prostitution, maybe in an informal outdoor brothel. But what we’re shown cannot be called sex trafficking unless we hear from the women themselves whether they opted into this situation on any level at all. They aren’t in chains and no guns are pointed at them, although they might be coerced, frightened, loaded with debt or wishing they were anywhere else. But we don’t hear from them. I’m not blaming the reporters or police involved for not rushing up to ask them, but the fact is that their voices are absent.

…

There are lots of things we might find out about the fields near San Diego… [but] we don’t see evidence for the sex-trafficking story. Feeling titillated or disgusted ourselves does not prove anything about what we are looking at or about how the people actually involved felt.

Regarding a news clip, Agustin writes:

…a reporter dressed like a tourist strolls past women lined up on Singapore streets, commenting on their many nationalities and that ‘they seem to be doing it willingly’. But since he sees pimps everywhere he asks how we know whether they are victims of trafficking or not? His investigation consists of interviewing a single woman who… articulates clearly how her debt to travel turned out to be too big to pay off without selling sex. Then an embassy official says numbers of trafficked victims have gone up, without explaining what he means by ‘trafficked’ or how the embassy keeps track…

So here again, there could be bad stories, but we are shown no evidence of them. The women themselves, with the exception of one, are left in the background and treated like objects.

To recap, what Agustin is urging us to do is to refrain from excluding the possibility of women’s agency by definition. Why might a woman choose a dangerous, stigmatized, and likely unpleasant job? Well, many women enter prostitution “voluntarily” because of social structural conditions (e.g., they need to feed their children and prostitution is the most economically-rewarding work they can get). Assuming all women are forced by mean people, however, makes the social structural forces invisible. We don’t need mean pimps to force women into prostitution, our own social institutions do a pretty good job of it.

And, of course, we must also acknowledge the possibility that some women choose prostitution because they like the work. You might say, “Okay, fine, there may be some high-end prostitutions who like the work, but who could possibly like having sex with random guys for $20 in dirty bushes?” Well, if we decide that the fact that their job is shitty means that they are “coerced” in some way, we need to also ask about those people that “choose” other potentially shitty jobs like migrant farmwork, being a cashier, filing, working behind the counter at an airline (seriously, that must suck), factory work, and being a maid or janitor. There are lots of shitty jobs in the U.S. and world economy. Agustin simply wants us to give women involved in prostitution the same subject status as women and men doing other work.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.