Kids growing up in dense, urban environments often turn to basketball as their sport of choice. This is partly because it fits, in a physical sense. All things being equal, a basketball court takes up a lot less room than a football or soccer field. For the economically disadvantaged, it’s also relatively cheap to play. If you have a court available, you only need a pair of shoes and a ball. For this reason, whatever population finds itself in this type of environment tends to take up basketball.

That’s why the sport was dominated by Jews in the first half of the 1900s. Just like many African-Americans today, at that time many immigrant Jewish families found themselves isolated in inner cities. Basketball seemed like a way out. “It was absolutely a way out of the ghetto,” explained retired ball player Dave Dabrow. Basketball scholarships were one of the few ways low income urban Jews could afford college.

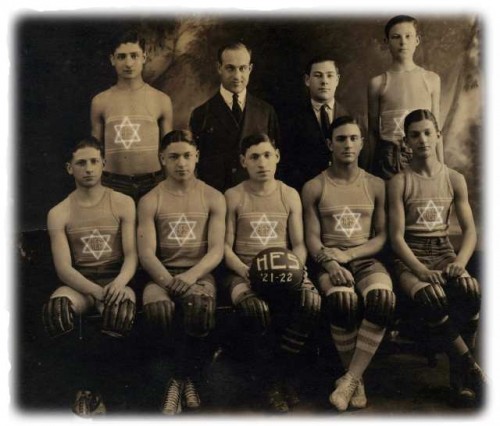

Jewish basketball team (1921-22):

Today we refer to stereotypes about Black men to explain why they dominate basketball, but this is an after-the-fact justification. At the time, very different characteristics — stereotypes associated with Jews — were used to explain why they dominated professional teams. Paul Gallico, sports editor of the NY Daily News in the 1930s, explained that “the game places a premium on an alert, scheming mind, flashy trickiness, artful dodging and general smart aleckness.” All stereotypes about Jews. Moreover, he argued, Jews were rather short and so had “God-given better balance and speed.” Yep. There was a time when we thought being short was an advantage in the sport of basketball.

Never underestimate the power of institutions and how much things can change.

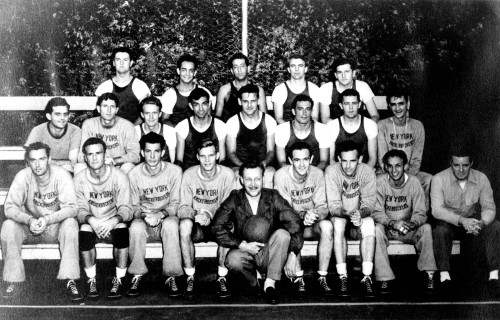

New York Knicks (1946-1947):

Cross-posted at Pacific Standard.

Cross-posted at Pacific Standard.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.