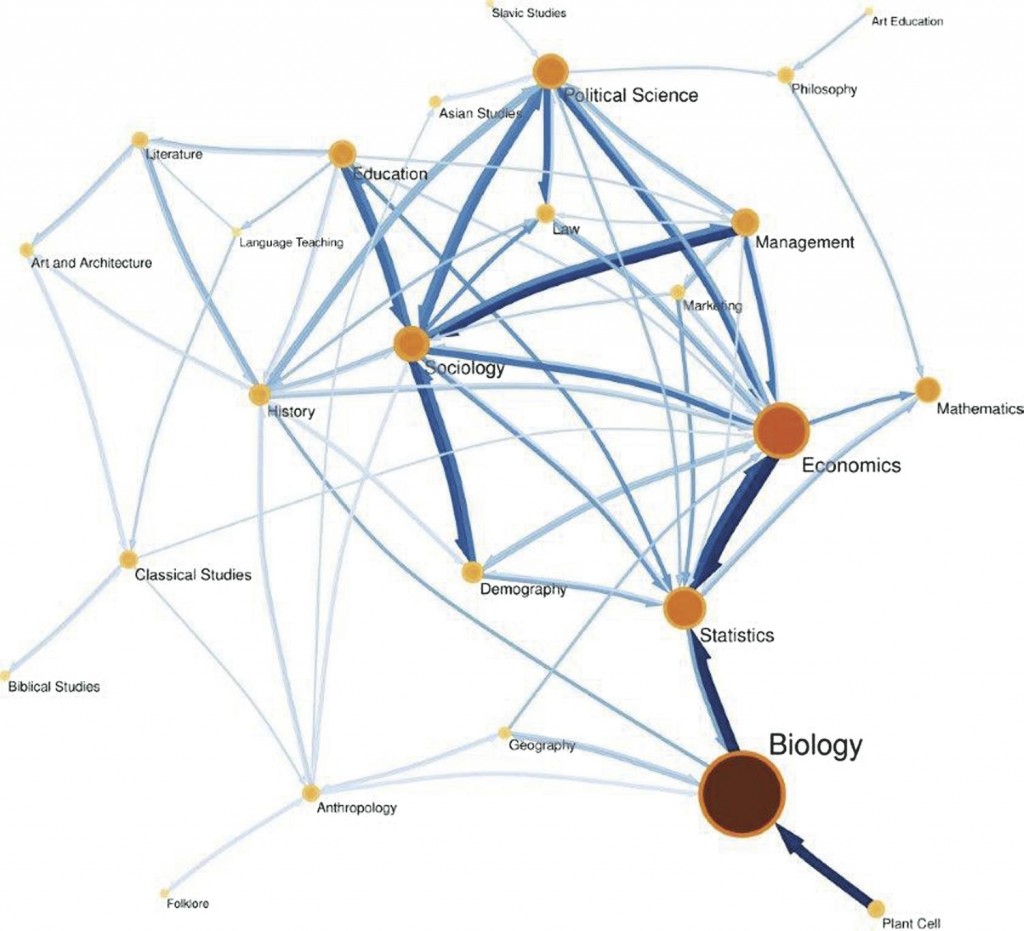

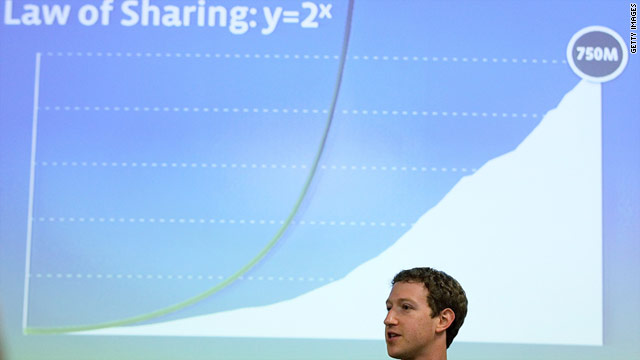

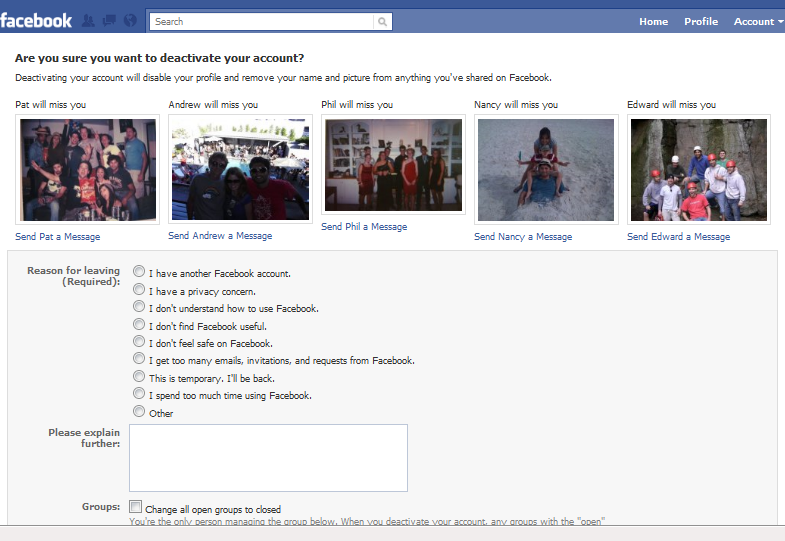

Network effect is a concept from economics that explains situations in which something becomes more valuable as more people use it. The classic example is the telephone; as more people and businesses adopted telephones, they became more useful (you could call a larger number of people you might wish to contact). More usage increased the value of the product, both for existing users and potential users. Social media work much the same way — an issue Google has faced as they try to pull enough users into Google+ to make it competitive with Facebook.

Over the weekend Matthew Hurst posted a video at Data Mining that illustrates the network effect…with dancers using an open area at the Sasquatch music festival. The video starts out a little slow; one guy starts dancing in the field, and a second guy joins him. For about a minute, it’s just the two of them. At 0:54, a third dancer appears. Through all of this, the surrounding crowd mostly ignores them, showing no inclination to participate. But at 1:12, a couple more people arrive, following immediately by more, and suddenly we’ve reached a tipping point: that open area is now a highly desirable spot to dance. People start running in from all directions, and many who had been ignoring the dancers suddenly jump up and join. It’s a great illustration of instances in which use drives more and more use: