Anita Sarkeesian is back with a new installment in her feminist analysis of video games. This one is a 25 minute discussion of the Ms. Male Character Trope, the phenomenon in which video games spice up their characters by including a female modeled off of the original male character. It’s a good example of the way in which males are centered, while females, if included at all, are seen as a non-normative kind of human, animal, or thing.

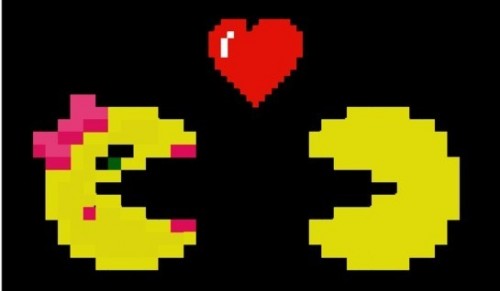

She starts with the classic example of Pac-Man and Mrs. Pac-Man, observing that only Mrs. is marked with symbols of femininity; Pac-Man, who’s not even called Mr. Pac-Man, has no markers at all. This is typical. This is how maleness is made simultaneously invisible and front-and-center, while femaleness is othered. Like this:

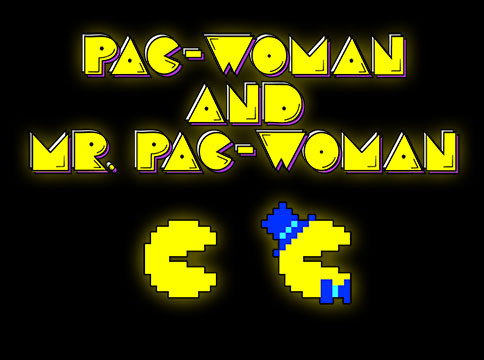

A fan sent her an example of what a reverse world would look like, where women were the default and men were marked and othered. Awesome:

Here’s the whole video:

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.