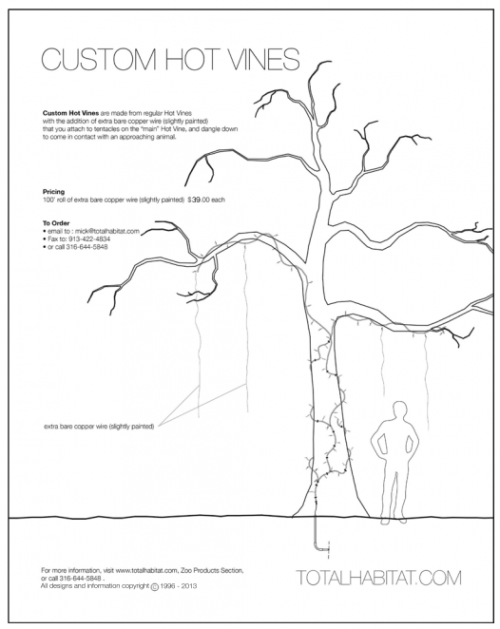

All eyes are on the Confederate flag, but let’s not forget what enabled Roof to turn his ideology into death with such efficiency, as illustrated in this comic from Jonathan Schmock. Visit Schmock’s website here.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.