In a previous post I discussed how the U.S. became more religious in the 1950s, in part in response to its the Cold War enemies (atheist communists). In fact, the U.S. is among the most religious countries in the world. Using data from the International Social Survey Programme, Sociologist Tom Smith paints wildly different religious portraits of 28 nations (full text).

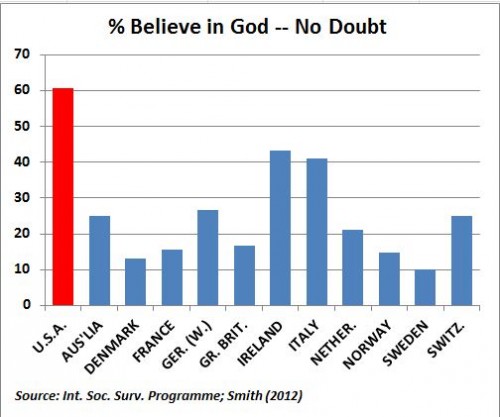

When asked whether they “know that God really exists and… have no doubt about it,” 61% of Americans say “yes.” Of the 28 nations studied, only four were more likely to say “yes” to this question: Poland, Israel, Chile, and the Philippines. Here’s how we look compared to similar countries:

Here’s all 28 in rank order (borrowed from LiveScience). Notice how wide the divergence is. In Japan, the least religious country according to this measure, only 4% say they have no doubt God exists. In The Philippines, 84% have no doubt.

% Have No Doubt God Exists:

- Japan: 4.3 percent

- East Germany: 7.8 percent

- Sweden: 10.2

- Czech Republic: 11.1

- Denmark: 13.0

- Norway: 14.8

- France: 15.5

- Great Britain: 16.8

- The Netherlands: 21.2

- Austria: 21.4

- Latvia: 21.7

- Hungary: 23.5

- Slovenia: 23.6

- Australia: 24.9

- Switzerland: 25.0

- New Zealand: 26.4

- West Germany: 26.7

- Russia: 30.5

- Spain: 38.4

- Slovakia: 39.2

- Italy: 41.0

- Ireland: 43.2

- Northern Ireland: 45.6

- Portugal: 50.9

- Cyprus: 59.0

- United States: 60.6

- Poland: 62.0

- Israel: 65.5

- Chile: 79.4

- The Philippines: 83.6

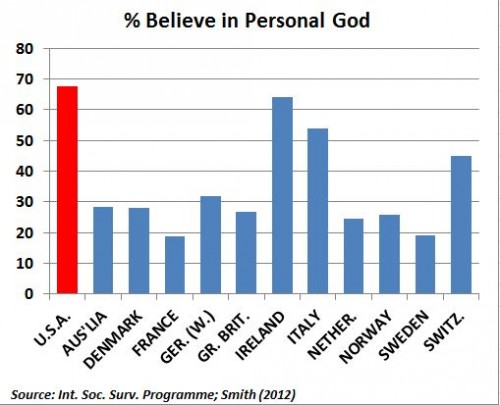

Americans are also particularly likely to believe in a “personal God,” one who is closely attentive to the lives of each and every person.

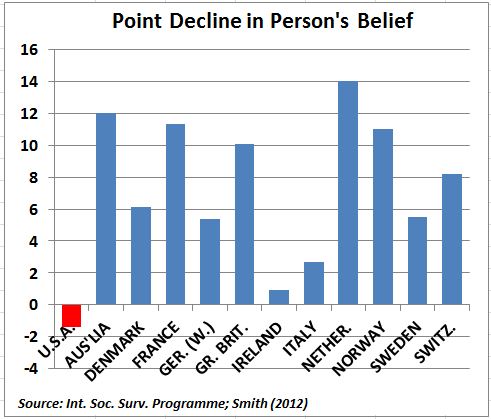

Quite interestingly, the U.S. is in the minority in that Americans tend to become increasingly religious as they age. In most countries, people become less religious over time. This graph (confusingly labeled), shows changes in DISbelief over the life course. The U.S. is the only country among these in which disbelief declines:

Lifetime Change in Religiosity (from increase in disbelief to increase in belief):

- The Netherlands: -14.0

- Spain: -12.4

- Australia: -12.0

- France: -11.3

- Norway: -11.0

- Great Britain: -10.1

- Switzerland: -8.2

- Germany (East): -6.9

- Denmark: -6.1

- Czech Republic: -5.5

- Sweden: -5.5

- Germany (West): -5.4

- New Zealand: -4.0

- Italy: -2.7

- Poland: -1.8

- Japan: -1.5

- Ireland: -0.9

- Chile: +0.1

- Cyprus: +0.2

- Portugal: +0.6

- The Philippines: +0.8

- Hungary: +1.0

- Northern Ireland: +1.0

- United States: +1.4

- Israel: +2.6

- Slovakia: +5.6

- Slovenia: +8.5

- Latvia: +11.9

- Russia: +16.0

Rates of atheism — a strong disbelief in God — also vary tremendously. East Germany is the most atheist, with more than half of citizens claiming disbelief. The country is a stark contrast to the atheist among them, Poland and the U.S. (only 3% atheist), Chile and Cyprus (2%), and The Phillipines (1%).

% Atheist:

- East Germany: 52.1

- Czech Republic: 39.9

- France: 23.3

- The Netherlands: 19.7

- Sweden: 19.3

- Latvia: 18.3

- Great Britain: 18.0

- Denmark: 17.9

- Norway: 17.4

- Australia: 15.9

- Hungary: 15.2

- Slovenia: 13.2

- New Zealand: 12.6

- Slovakia: 11.7

- West Germany: 10.3

- Spain: 9.7

- Switzerland: 9.3

- Austria: 9.2

- Japan: 8.7

- Russia: 6.8

- Northern Ireland: 6.6

- Israel: 6.0

- Italy: 5.9

- Portugal: 5.1

- Ireland: 5.0

- Poland: 3.3

- United States: 3.0

- Chile: 1.9

- Cyprus: 1.9

- The Philippines: 0.7

As a post-9/11 American watching another election cycle, I can’t help but notice how so much of our rhetoric revolves — sometimes overtly and sometimes not — around people who are the wrong religion. Notably, Muslims. And yet, the U.S. and many Muslim countries are alike in being strongly religious, at least in comparison to the many strongly secular countries.

This is odd because stands in contrast to recent data on American attitudes. Within the U.S., people express much less tolerance for atheists than they do Muslims (homosexuals, African Americans, and immigrants). Weirdly, we think we have more in common with more secular nations like Great Britain than we do with countries like Pakistan or Saudi Arabia. In certain ways, the opposite might be true.

Thanks to Claude Fischer for the graphs. Fischer, a sociologist at UC Berkeley, is the author of Made in America: A Social History of American Culture and Character.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.