Cross-posted at Family Inequality.

In 1994, Sara McLanahan and Gary Sandefur published, Growing Up With A Single Parent: What Hurts, What Helps. The growth of children living with only their mothers was — then as now — a matter of concern not only for children’s well-being, but for intergenerational mobility. One of their empirical conclusions was this:

For children living with a single parent and no stepparent, income is the single most important factor in accounting for their lower well-being as compared with children living with both parents. It accounts for as much as half of their disadvantage. Low parental involvement, supervision, and aspirations and greater residential mobility account for the rest.

The biggest problem, in other words, is economic. The other factors — involvement, supervision, aspirations, mobility — are related to social class and the time poverty that economically-poor parents experience.

Examples

Here are some bivariate illustrations — that is, head-to-head comparisons of the difference between children of poor and non-poor versus single and married parents.

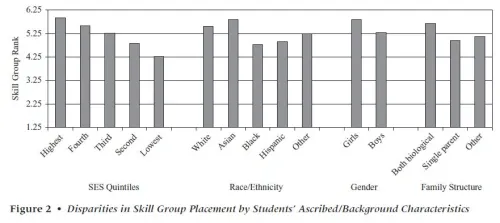

These are the “skill group” rankings by teachers of children by socioeconomic status (or SES, a composite of parents’ education, occupational prestige and income) versus race/ethnicity, gender and family structure. SES shows the widest spread in reading teachers’ group placement of first graders.

Source: Condron (2007)

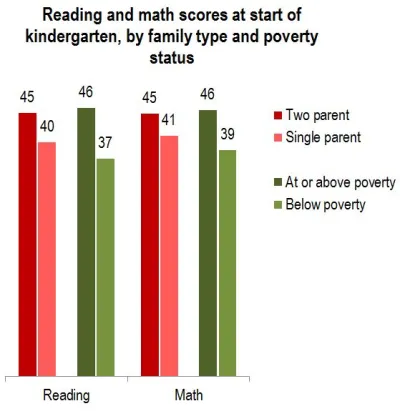

Similarly, the poor/nonpoor difference is greater than the two-parent/single-parent difference in kindergarten entry scores:

Source: Early Childhood Longitudinal Study (2009)

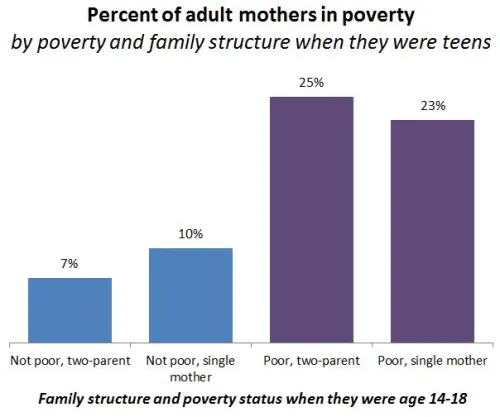

Those are just two examples from early-childhood assessments. More importantly, here is the breakdown seen in a longitudinal study of children growing up. When women grow up to be mothers, their poverty level in childhood is more important than their family structure for predicting whether they will be in poverty themselves. The poverty difference is large, the family structure difference is not:

Source: Musik & Mare (2006)

This study included a more sophisticated set of multivariate analyses than this simple graph, but the author’s conclusion fits it:

Net of the correlation between poverty and family structure within a generation, the intergenerational transmission of poverty is significantly stronger than the intergenerational transmission of family structure, and neither childhood poverty nor family structure affects the other in adulthood.

That is, childhood poverty matters more.

Fewer single parents, or less poverty?

But if single parenthood and poverty are so closely related, some people say, we should spend hundreds of millions of dollars promoting marriage to help children avoid poverty (and other problems). That’s what the government has done, with money from the welfare budget. Even if it worked, which it apparently doesn’t, it’s only one approach. What about reducing poverty? And, more specifically, reducing the relative likelihood of poverty in single-parent families versus those with married parents. That is, address the poverty gap between the two groups, rather than the size of the two groups. This has the added advantage of not singling out one group — single mothers — for social stigmatization (of the kind I mentioned here). And, because it defines the problem as economic rather than moral, may make it easier to build public support for helping the poor.

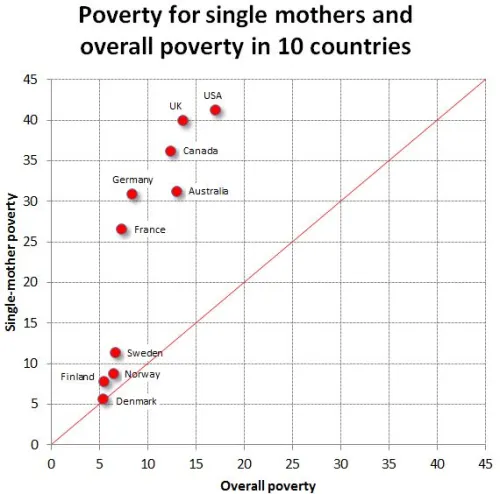

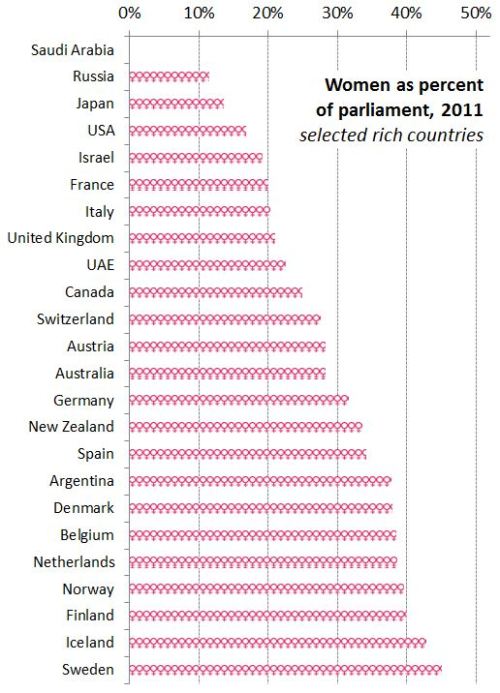

Consider a recent paper by David Brady and Rebekah Burroway, which will be published in Demography. They analyzed the relative poverty of single mothers versus the total population — that is, what percentage had incomes below half the median (per person, after accounting for taxes and government transfers). Such a relative poverty measure is really a measure of inequality, but specifically inequality at the low end. (Regardless of how rich the rich are, it’s theoretically possible to have no one below half the median income). Here is my graph showing that result, with only the countries that have reliable sample sizes in the survey:

The Nordic countries have the lowest overall poverty rates. But in absolute terms their advantage is much bigger for single mothers. (The red line shows equal poverty rates for single mothers and the total population.) The US and UK have the largest difference in poverty rates between single mothers and overall poverty. That is, we have the largest poverty penalty for single motherhood. If the relative poverty rates for single mothers were lower in the US, we might spend more time and money addressing poverty and less trying to change family structures.