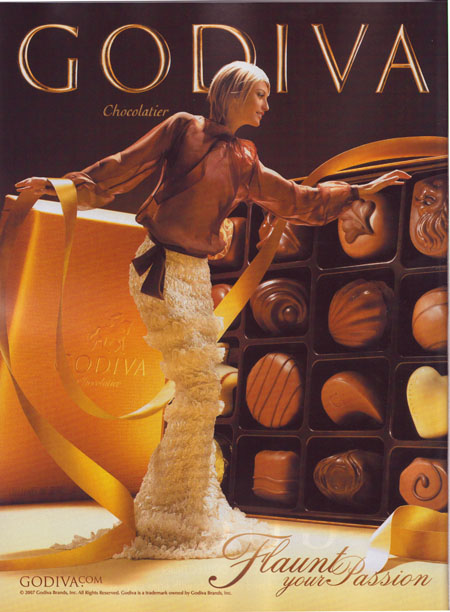

In consumer society, products sell an image of the consumer to others. Chocolate, for example, can bring prestige if it comes from a particular manufacturer and falls within a certain price range. The design and ideology behind Godiva for example, promotes a sophisticated chocolate and uses powerful imagery to convince consumers that they may attain an unparalleled experience of high-class luxury.

Godiva promotes the idea that consumers of their chocolates are somehow “higher class” and more “tasteful” than people who do not consume them. As a result, their chocolates have a higher exchange value than the everyday, $1 chocolates meant for middle and lower-class consumers.

Many chocolate connoisseurs argue that Godiva chocolates taste like sugar and candle wax, failing to satisfy the European taste criteria for elite chocolate. Nevertheless, the reputation of Godiva as luxurious is enough to satisfy many non-connoisseurs and it, accordingly, maintains a high exchange-value. Hoping to capitalize on the trend, many popular brands have released their own line of “premium” chocolates hoping to reap profits far out of proportion to the cost of production.

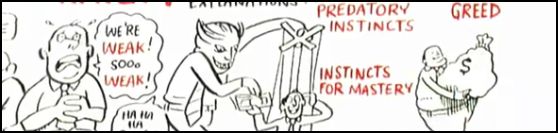

From a Marxist viewpoint, status-symbol chocolate advertising exemplifies how fetishization helps maintain capitalism. Such advertising tacitly legitimizes the elite class by reinforcing the image of upper-class superiority and by presenting the luxurious lifestyle as something to aspire to. It also helps foster false consciousness, which lulls the oppressed working class into complicity, even or especially when prices for “premium” chocolates fall suspiciously low.

Is fair trade a resolution to chocolate’s fetishism?

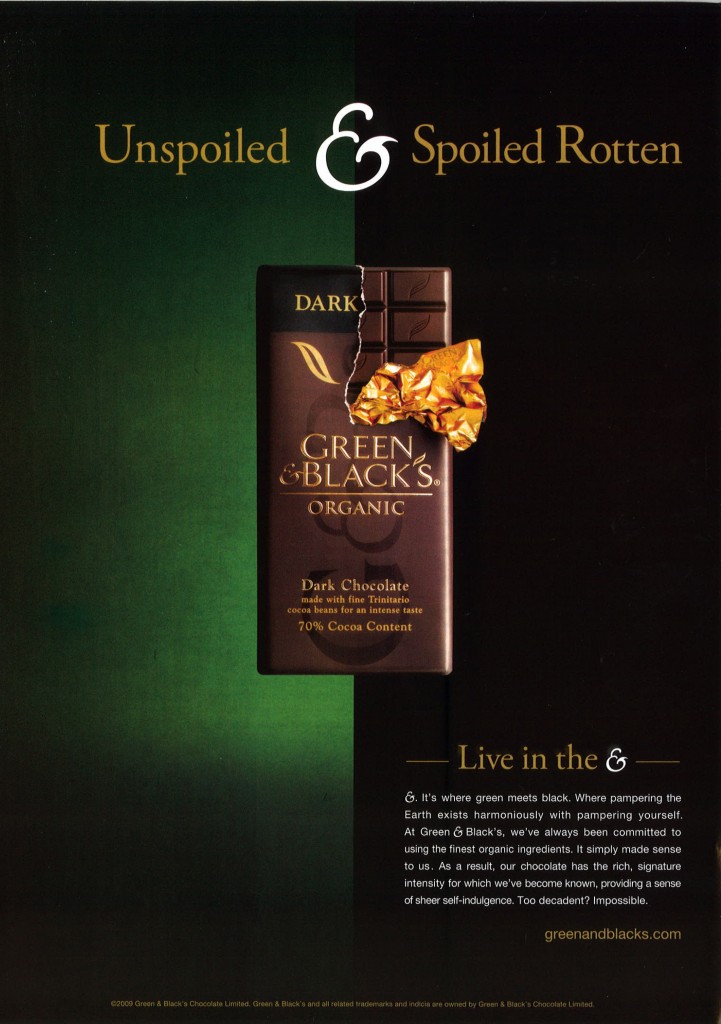

Chocolate’s fetishism is partially resolved through Fair Trade, which redistributes some of those profits back to the working class and makes the consumer conscious of the worker.

The fetishism of chocolate is only partly resolved, however, since the owning class continues to profit from the fetishism of the commodity and from the enhancing status of the “Fair Trade” label. The purchasing of Fair Trade chocolate, you see, provides the consumer with some emotional comfort; it flatters them just as a high end chocolate product flatters buyers who identify themselves as elite. Therefore, there is an increase in the consumer’s cultural capital with the purchase of Fair Trade chocolate. It is still fetishism to the extent that the consumer is purchasing a comforting emotion or an image of themselves saving the world, which is encouraged by advertising campaigns and wrapper designs. However, in an interesting twist, fetishism is used to reverse the effects that it is traditionally guilty of: benefiting the upper-class at the expense of the lower-class.

————————-

Jamal Fahim graduated from Occidental College in 2010 with a major in Sociology and a minor in Film and Media Studies. He was a member and captain of the Occidental Men’s Tennis team. Jamal currently lives in Los Angeles with the intention of working in the film industry as a producer. His interests include film, music, digital design, anime, Japanese culture, improvising, acting, and of course, chocolate!

If you would like to write a post for Sociological Images, please see our Guidelines for Guest Bloggers.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.