Sociology Twitter lit up after the US Women’s National Team’s World Cup win with the revelation that many of their players were sociology majors in college. It is an inspiration to see the team succeed at the highest levels and call for social change while doing so.

This news also raised an interesting question: do student athletes major in sociology because it is a compelling field (yay, us!) or because they are tracked into the major by academic advisors who see it as an “easy” choice to balance with sports?

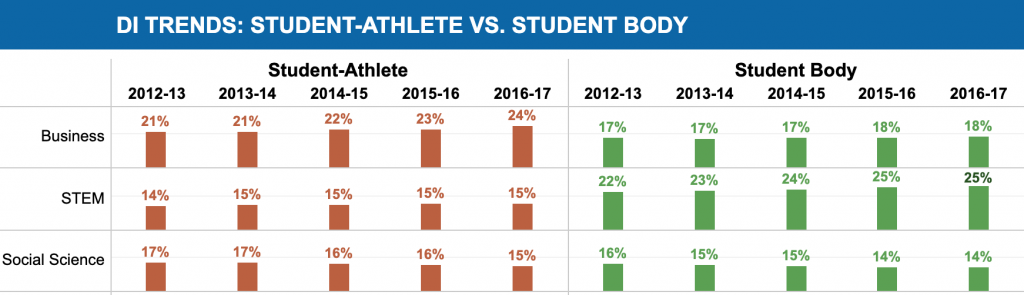

According to data from the NCAA, the most common majors for both student athletes and the wider student body at Division 1 schools are business, STEM, and social sciences. Trend data show the biggest difference is in the choice between business and STEM; both groups seem to pick up social science majors at similar rates.

While the rate of majors is not that different, there is something special that sociology can do for these students. Student athlete lives are heavily administered. Between practice, conditioning, scheduled events, meals, and classes, many barely have a few hours to complete a full load of course work. In grad school, I tutored many student athletes who were sociology majors, and I watched them juggle their work with the demands of heavy travel schedules and intense workouts, all under the watchful eye of an army of advisors, coaches, mentors, and doctors. The experience is very close to what Erving Goffman called a “total institution” in Asylums:

“A total institution may be defined as a place of residence and work where a large number of like-situated individuals, cut off from the wider society for an appreciable period of time, together lead an enclosed, formally administered round of life. (1961, p. xiii)”

We usually associate total institutions with prisons and punishment, but this definition highlights the intense management that defines the college experience for many student athletes. When I tutored athletes in sociology, we spent a lot of time comparing their readings to the world around them. Sociological thinking about institutions, bureaucracy, and work gave them a language to think about and talk about their experiences in context.

Athletic programs can be complicated for colleges and universities, and there is ongoing debate about how the “student” status in student athlete shapes their obligation to pay for all this work. As debates about college athletics continue, it is important for players, fans, and administrators to think sociologically about their industry to see how it can better serve players as both students and athletes.

Evan Stewart is an assistant professor of sociology at University of Massachusetts Boston. You can follow his work at his website, on Twitter, or on BlueSky.

Many hope that

Many hope that