While there has been significant attention to recruiting women into STEM fields, what about the converse – recruiting men to female-dominated fields? My recent article in Gender & Society analyzes the recruitment strategies of key health care players, examining themes of masculinity in text, speech, and images.

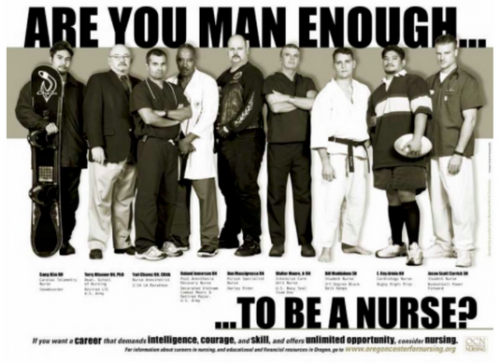

Some recruitment items, like this early poster from the Virginia Partnership for Nursing, asked viewers “Are you man enough to be a nurse?” Aspects of hegemonic masculinity — characteristics associated with being the culturally defined “ideal man” — are common themes in the poster, including sports, military service, risk-taking, and an emotionally-reserved demeanor:

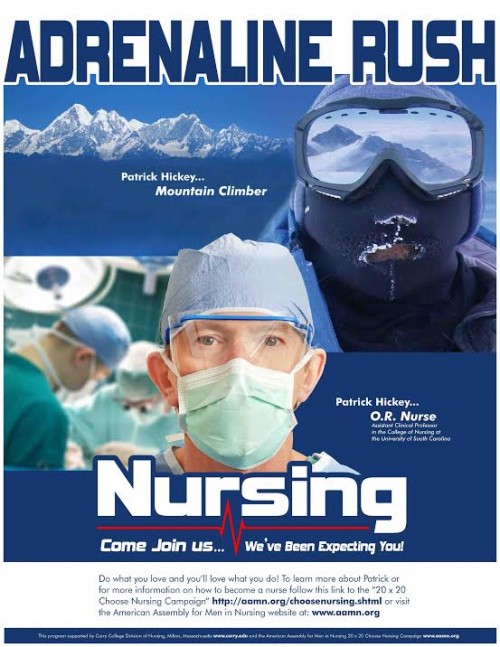

Since the “Are You Man Enough?” campaign in the early 2000’s, nurse leaders have tried to make recruitment messages less ostensibly gendered. In discussing the American Assembly for Men in Nursing’s (AAMN) new campaign, Don Anderson notes:

Nursing recruitment efforts needed to evolve from asking men if they were masculine enough to be a nurse to something less gender specific

Despite the effort to “de-genderify” nursing (Anderson’s word), masculinity is still front and center. Though the slogan is different, materials continue to emphasize culturally idealized forms of masculinity. One of the AAMN’s newest posters, “Adrenaline Rush,” avoids the “man enough” rhetoric, but maintains the theme of a stoic, emotionally-detached masculinity through visual cues. Most of the nurse’s face is covered – limiting emotional expression—while risk-taking is emphasized.

But not all recruitment materials employ a macho form of masculinity. Johnson & Johnson’s 30-second clip “Name Game” portrays a caring and emotionally competent nurse:

Key health care players, including an international organization (Johnson & Johnson), urban hospital systems, nursing programs, and organizations like the American Assembly for Men in Nursing (AAMN) have devoted resources to recruiting men into nursing. Analyzing their recruitment strategies reveals as much about contemporary tensions within masculinity as it does about the profession’s push for gender diversity.

Check out more of the recruitment materials and a more in-depth analysis in the article, “Recruiting Men, Constructing Manhood: How Health Care Organizations Mobilize Masculinities as Nursing Recruitment Strategy.” For a free copy, contact me at cottingham@unc.edu.

Marci Cottingham is a postdoctoral fellow in the department of Social Medicine at the University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill. She received her Ph.D. in sociology from the University of Akron. Her research spans issues of gender, emotion, health, and healthcare. For more on her work, visit her site.

Cross-posted at Pacific Standard.